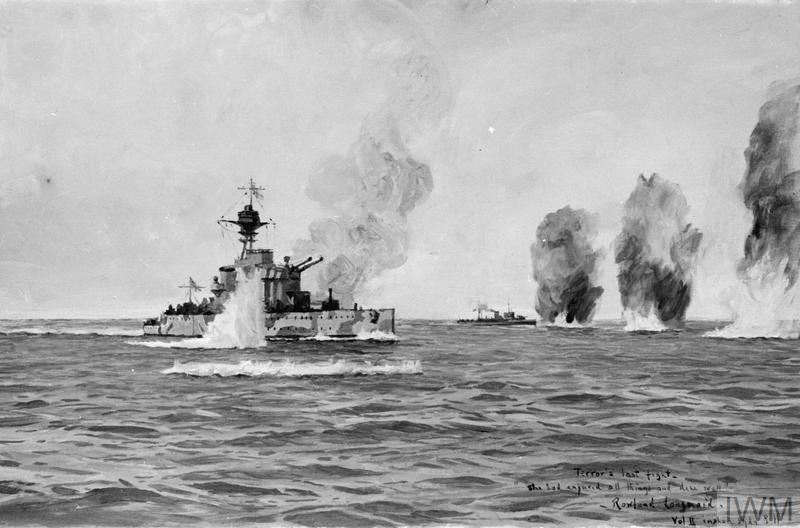

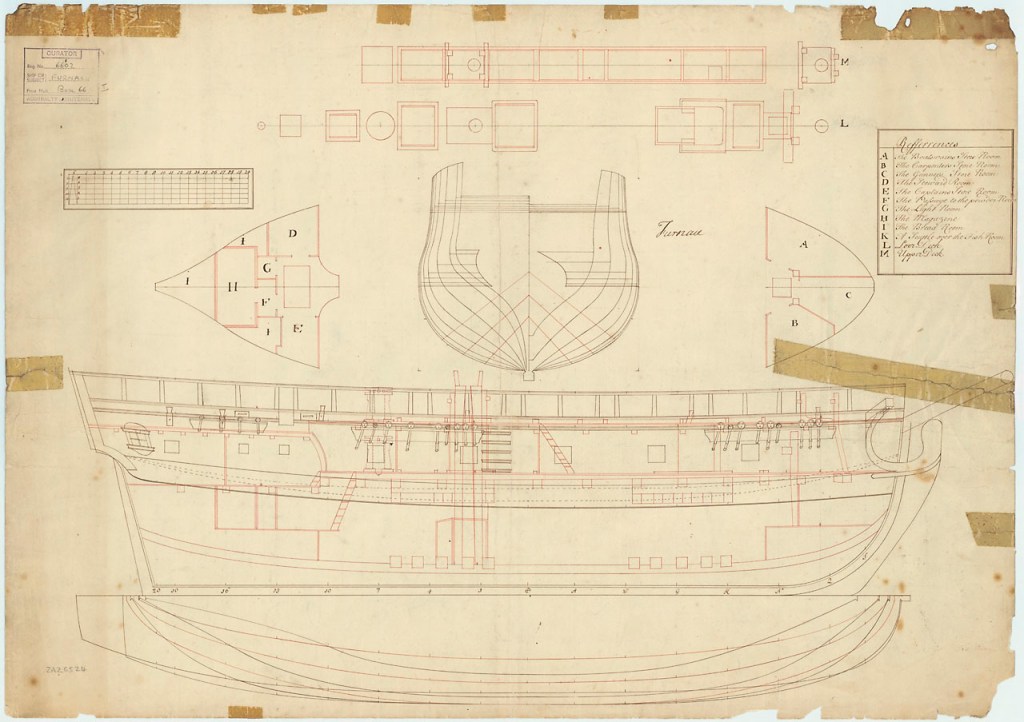

On that fateful day of May 19th, 1845, when the crews of Sir John Franklin’s last expedition in search of the Northwest Passage departed Greenhithe, England – never to return – they did so onboard two incredible vessels. Her Majesty’s Ships Erebus and Terror hadn’t originally been designed for polar exploration. Rather, these were both examples of a highly specialized type of warship called a “bomb vessel.” Why send a warship that was meant to bombard enemy positions on a polar exploration mission? This post briefly explores the history and design of the first bomb vessel that was sent north, HMS Furnace, which left England in 1741 on an earlier effort to locate that same illusive passage to the Pacific Ocean.1 Did Furnace blaze a trail across the frozen northern latitudes? Not exactly, but her modifications for exploration set an important precedent for a lineage of tough little ships which would be used on Arctic and Antarctic exploration missions.2

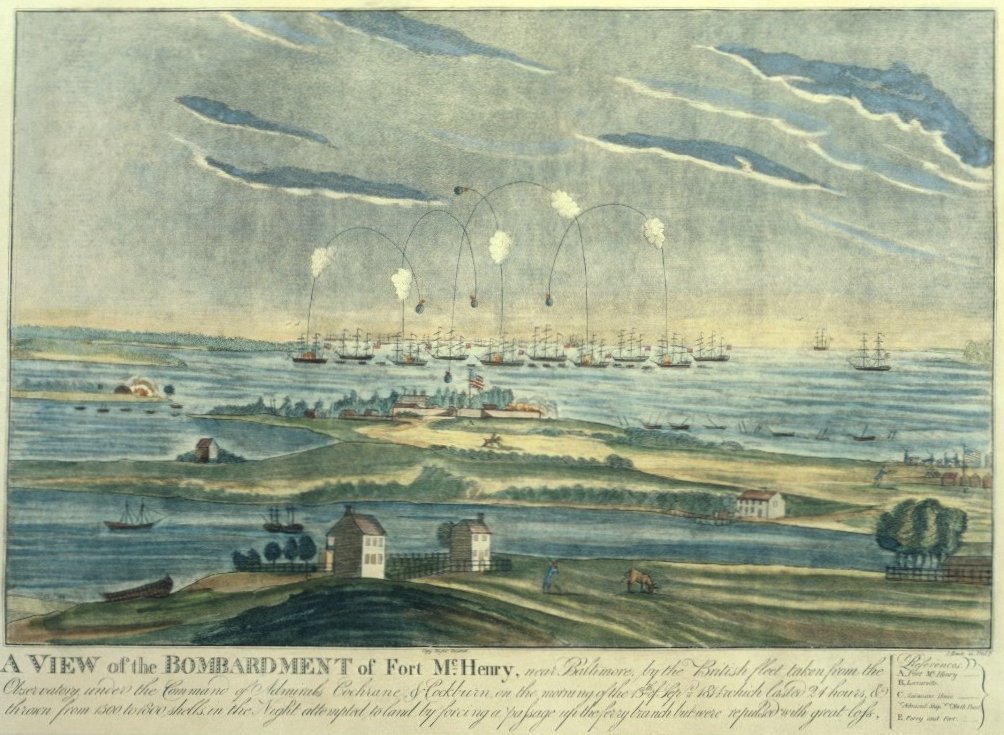

Maritime historian and former National Maritime Museum curator Chris Ware’s work on the history of bombs, The Bomb Vessel: Shore Bombardment Ships in the Age of Sail, explores the history of the Royal Navy’s bomb vessels, and highlights the careers of selected ships.3 The type had been created late in the 17th century to carry one or two heavy mortars amidships. Like many other great British naval developments, the idea had come from France, whose navy had built the first bomb vessels, galiotes à bombes, starting in 1681.4 The mortars (which had been developed originally for land warfare) fired types of fused shells called bombs (explosive) or carcasses (incendiary) on a high trajectory over the bulwarks. They were used against fortifications or cities and towns. The bombs would plunge downwards to explode against or over targets.

To carry the massive mortars and handle their powerful recoil, which was transmitted down from their carriage directly into the wooden timbers of the vessel, bombs had to be very strongly built: They were framed, decked, and reinforced much more stoutly than other ships of their relatively small size. While the first English bombs resembled small coastal craft, by the 1730s new designs appeared that were closer to naval sloops.5 There were usually only a handful of bombs active at any given time. Most spent the vast majority of their careers out of commission or converted to other roles. The Board of Ordnance, which had responsibility for both the guns and the specialist personnel to work them, would unship and land the mortars to help preserve these valuable weapons. When being used as patrol vessels, a stronger battery of cannon was installed along the gundeck.

In contrast to the great and tragic expeditions that came both before and after, Christopher Middleton’s Northwest Passage Expedition of 1741 is rarely mentioned, even in exploration literature. This 1741-1742 bid to locate the storied Passage, or “Straits of Anian” deserves more attention. Middleton was an experienced ship’s captain and a skilled navigator who had conducted a variety of scientific observations (including magnetic studies) while sailing to and from Hudson’s Bay, on annual supply missions for the Hudson’s Bay Company. He had an early enthusiasm for exploration, the search for the Northwest Passage, and also an interest in establishing the fate of the vanished James Knight expedition of 1719.6 Middleton had been nearby at the HBC Factory at the Churchill River (present-day Churchill, Manitoba) when, unbeknownst to anyone, the crews of Knight’s two small ships were marooned on Marble Island.7 In recognition of his scientific publications, Middleton was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1737. In 1741, having left the employ of the HBC, the Royal Navy appointed him to command HMS Furnace. His orders were to seek a Northwest Passage somewhere along the Western coasts of the Bay. In reviewing the available units of the fleet, this new and rugged generation of bombs must have seemed ideal candidates for an exploration mission, where ships were in danger of colliding with icebergs, grounding, or being forced ashore out in Baffin Bay or the Hudson Strait, or being damaged or crushed by pack or land ice. Furnace would be accompanied by a hired collier, HMS Discovery, which was commanded by Middleton’s cousin, William Moor. The Admiralty optimistically believed that, a Passage having been located and exploited, the ships might link up with Commodore George Anson’s 1740-44 circumnavigation of the World, somewhere in the Pacific.

After crossing the Atlantic, the officers spent a terrible winter at Prince of Wales Fort to get an early start to the season. Expedition members stayed ashore in a disused wooden fort.8 They first prepared the ships for being iced into the harbour – with Furnace becoming the first bomb to overwinter. Once the exploration work commenced in July 1742 they quickly discovered that a promising inlet did not in actuality offer any corridor to the west (Middleton thought this a river and named it “Wager” after Sir Charles Wager, First Lord of the Admiralty, but it was later determined to be a bay). Other useful exploration work included the discovery of Repulse Bay (now known as Naujaat) and the assessment that the Frozen Straits offered no likely passage to the west. With the crew weakening from scurvy, and the major exploration work having led to dead-ends, Middleton hastened back to England.9

Middleton’s surveying work was attacked after his return, with Arthur Dobbs (a wealthy and influential Irish landowner who has supported Middleton’s original appointment) and Moor both coming around to the view that not enough had been done to rule Hudson’s Bay out as the beginning of a passage towards the Pacific.10 Moor departed on another expedition which explored more of the same coasts of the Bay. Future expeditions would take other reinforced bomb vessels further north to continue the search for a navigable passage amongst the Arctic islands. As William Barr has pointed out, the criticisms Middleton was subjected to were baseless, and the accuracy of his surveying was eventually confirmed.11

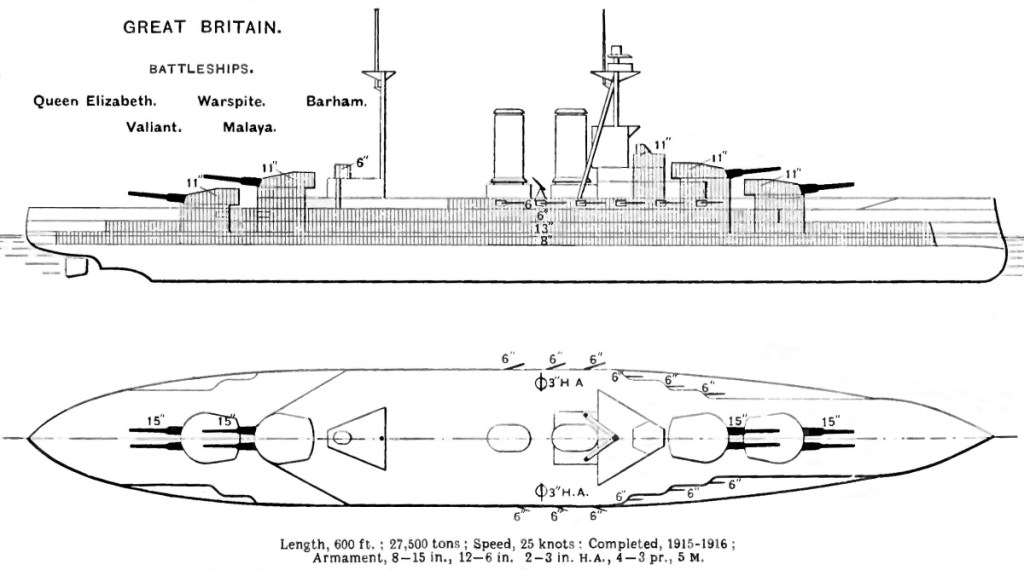

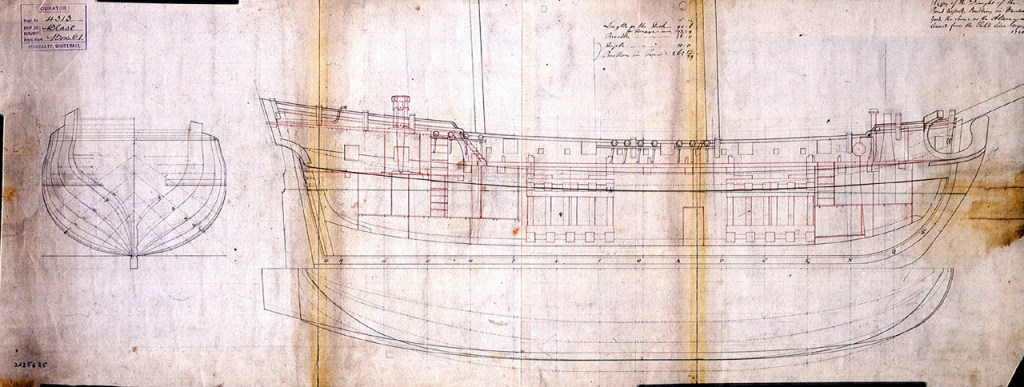

HMS Furnace was a Blast class bomb vessel, completed in October 1740 by Quallett (presumably the commercial yard of John Quallett of Rotherhithe in South London, which built other Royal warships such as HMS Chesterfield and several sloops). She was 91.5 feet long on the gundeck and 26’4” broad, with an 11-foot draft. All told she was almost 273 tons burthen.12 This new class of six bomb vessels were rushed into service as war broke out again against Spain in late 1739. As the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748) spread across Europe, a second group of five almost identical sisterships were constructed the next year. Among them was the second bomb vessel to be named HMS Terror.13

Like most early bomb vessels, Furnace was rigged as a ketch, with a tall mainmast and a shorter mizzen aft. This rig proved to be problematic for the complicated laying, or aiming of the mortars, as it left only a small arc of fire unimpeded by the masts, yards, rigging and shrouds. When it came to the deck machinery, earlier bombs had been fitted with windlasses (horizontal drums) to assist in heavy tasks such as lifting the anchor cables, or the complex effort of warping the ship around on the anchor cables to precisely aim the mortars. The Blast ships, by contrast, were also fitted with the more powerful capstan (vertical drum) on the quarterdeck.14

HMS Grenado, a near-contemporary of Furnace, is depicted in a superb sectional model at the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, which helps us explore the peculiarities of the design:

We can observe a robust, wide hull, with closely-spaced frames. The solid construction continued into heavy knees supporting the deck beams. In Grenado and Furnace, the mortars were originally sited forward and aft of the mainmast, while the mizzen mast rises above the deck just forward of the break on the quarterdeck. A new type of mortar had been developed, which could elevate and depress on trunnions, and rotate in its octagonal pit. The mortars could be lowered and covered over with sliding hatches, and protected from the elements. The long run of the open waist amidships was necessary to provide the room needed to work the mortars. These ships, like the later Franklin vessels, were originally armed with a 13″ and a 10″ mortar. The secondary weapons, a battery of six light 4-pounder cannon, created a modest broadside for defensive purposes. Additional empty gunports, evenly spaced along the gundeck, allowed for the augmentation of these cannon when the mortars were unshipped. The officers’ cabins were tucked aft under a small quarterdeck, on a deck stepped slightly lower than the main run of the gundeck. There was a very small covered foc’sl forward of the large windlass, and between those was the usual belfry with ship’s bell.

As can be seen by comparing the above Admiralty plans, preserved at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, with the Grenado model or the plans at the beginning of this post, Furnace was extensively modified for exploration. The masts were relocated, with a third mast making the vessel a sloop.15 There are many elements of the design that set the pattern for the Admiralty modifying ships for polar exploration, right down to those final modifications to Franklin’s two ships. Middleton’s input on this refit – reflecting his HBC service in the Company sloops – was important. Compared to the unmodified bomb vessels, this ship now has a shorter, less vulnerable stem, and higher sides. The open waist where the two mortars were once sited has been decked-over. The mortars, beds, and cribbing have been removed down to the keel. Furnace even has channels that have been reinforced with ice chocks to make them less vulnerable.16 The ship now has a larger double capstan, installed further forwards between the mizzen and mainmast, which could be worked by crew on both weather and lower decks. The windlass near the bows has apparently been removed.17 Middleton was able to influence the Admiralty into equipping Furnace with a complement of boats he wanted. He was even able to secure an “ice boat” for this mission, which was a specialized craft that HBC sloops used, but that had not previously been on the establishment of any British warship.18

Once the crews were wintering ashore at Churchill, Middleton held a council with his officers to discuss further modifications to Furnace. His journal, reproduced in Barr and Williams’ edited Hakluyt Society publication, provides detailed information about the March-April 1742 design modifications.19 The carpentry work that Spring optimized the bomb-exploration conversion. The quarterdeck was built up to the level of the new main deck, to make a continuous weatherdeck. This fixed an issue where the stepped-down aft deck shipped too much water during foul weather. Middleton also recognized the limitations of steering the ship in adverse conditions with an old-style tiller. He supervised the construction and fitting of a ship’s wheel, with the old curving iron tiller bar straightened out. All subsequent bomb-derived exploration vessels would be equipped with ship’s wheels.

Upon the expedition’s return to England, Furnace was modified back to her original design. The overwintering and exploration work do not appear to have shortened her career: She served longer than all the other 1740-constructed bombs, being eventually decommissioned in 1763, after participating in several bombardments during the Seven Years War.20 HMS Furnace’s 1741 refit, – and Middleton’s expert modifications at Churchill – set the pattern for the modification of six other bomb vessels to be sent on future Arctic and Antarctic missions.21 This era ended more than a century later when the last two serviceable bombs disappeared into the Canadian Arctic.