During the age of fighting sail in Europe (ca. 1550-1860), naval architects competed to design larger ships, that could carry many more cannon that could fire heavier shot. The ultimate expression of this became the warship with three complete decks of large cannon: the “three-decker.”* These were the behemoths of any fleet, and the largest of the line of battle ships (those warships with heavy enough armament to lie in the main battle-line that fleets conventionally arrayed themselves to prepare for a battle). Only a few wealthy nations could afford to build, arm, and equip such ships. Objects of national prestige, lavishly decorated in fashionable artistic styles, their principal role was as a gun platform, whose firepower would be a useful addition to any battle line.

They had flagship accommodations for an admiral and their staff, and were floating headquarters to direct a squadron, a large fleet, the forces in a given area, a campaign, or an entire theatre of operations . During routine operations, or in the thick of battle, the officers of other ships would keep a weather eye out for signal flags from the flagship, and the massive size and height of their masts helped other ships see important signal flag hoists in the thick of battle, where cannon-smoke frequently could obscure whole sections of the engaged fleets.

These ships could bombard shore positions and fortresses, or serve for lengthy periods on blockade duty either close to enemy ports, or in a more distant, reserve position. As part of their enormous complement of up to 1,000, they usually had a contingent of marines or soldiers, who could conduct amphibious landings ashore. These soldiers-at-sea also formed a disciplined group during sea battles, with sharp shooters assigned to sweep the enemy decks with musket fire. When enemy ships came alongside, soldiers or marines helped resist enemy boarding parties, and carry the fight to the enemy’s decks.

The first of such ships is usually attributed to the English Navy.** Prince Royal (1610) began her career as a large ship with about 50-60 cannon, dispersed mostly over 2 decks. In those early days, she had a waist deck that was free of cannon. A later refit, in the 1620s connected the forecastle and quarterdeck batteries of guns. Through her lengthy career she was radically rebuilt several times, eventually being upgraded to a 92-gun three-decker. The structural changes of the rigging, gundecks, ornamentation, and gunports suggest she was virtually a new vessel.

For the remainder of the age of fighting sail, the size and firepower of the ships increased. The next English three-decker, and the first built as such, was the enormous and astronomically expensive Sovereign of the Seas of 1637. This ship boasted 102 brass cannon, and a ludicrously ostentatious decorative program that covered most of the vessel’s upper works with lavishly carved statuary and crests, the whole dripping with gold leaf paint. The absurd cost of this vessel, and the revenue required in “ship money” taxes to the government of King Charles I to complete it, were contributing factors to the outbreak of the English Civil War.

The Northern states also built three-deckers for service in their interminable wars. Both Sweden and the joint kingdom of Denmark and Norway produced some of the largest warships in the World in the late 17th Century. One Dano-Norwegian ship, the Sophia Amalia, was built during the 1640s to be larger, with more cannon, that the Sovereign of the Seas. The Swedish Kronan of 1672, with at least 110 guns, is also notable. After only a few years of service, it exploded at the Battle of Öland, 1 June 1676.

The French commenced building three-deckers in 1668, ranked according to their wonderfully descriptive title of “Vaisseaux de Premier Rang Extraordinaire.” Naval architects during the reign of Bourbon King Louis XIV quickly moved to larger ships, with 110 or more cannon, and French ships were noted for their beautiful lines and ornamentation.

Spain’s path to building the type started with the Nuestra Señora de la Concepción y de las Ánimas of 1687, a 94-gun three-decker. A contemporary plan of this ship can be seen at modelships.de site. Beginning in earnest around 1750, the Spanish began launching some massive designs, of which the largest, the Nuestra Señora de la Santísima Trinidad of 1769, will be discussed below.

In the very first years of the 19th Century, the Russians and the Ottoman Empire (which included Egypt) also began building large examples. In North America, the War of 1812 initiated a naval race on the Great Lakes that produced the huge HMS St. Lawrence, an unusual 112-gun ship, built in the naval yard at Kingston, Ontario.** The Americans abandoned construction on their equivalent ship, at Sackets Harbor, New York, which would have been named New Orleans (this hulk sat on the stocks at from 1815-1883). The United States later commissioned USS Pennsylvania in 1837.

The last of these ships were the largest, and most well-armed. They were built with strengthened interior bracing, that enabled ships to be built longer, with more guns. Some were fitted with newly-developed shell-firing cannon. They also had different styles of sterns and bows, which allowed for stronger hulls in these traditionally weak areas, with more cannon able to fire forward and aft.

The sheer became remarkably flat (so the decks, ship’s sides, and planking were almost without any curvature up towards the stern and bow), and even the tumblehome shape of the hulls were modified, with some designs having strait vertical sides. Ornamentation was kept to a minimum, and a stark chequerboard paint scheme of white strakes broken by black gun-ports became the norm. During the 1850s several ships were fitted with steam engines and screw propellers, and could sail or steam, depending on the conditions.

The age of the three-decker, like that of all wooden fighting ships, ended during the 1860s when ocean-going iron-clad warships, firing shells from rifled guns, quickly made large wooden ships obsolete. Ships that had consumed vast amounts of raw materials (including by deforesting several regions), and required enormous investments to outfit with provisions, large crews, and so many cannon, now had little military value. A few three-deckers survived as accommodation hulks, specialized training ships, hospital ships, prison hulks, and cadet and school ships.

Now that we have said our piece about the development of three-deckers, the remainder of the post will briefly explore four spectacular fighting ships: One original line of battle ship from the 18th Century, and three replicas of similar ships. According to the Royal Navy’s rating system, as it evolved over the course of the 18th Century, these would have mostly been considered “first rate” three-decker line of battle ships, which usually were defined as having 100 or more cannon.*** Though some ships in the period 1640-1760 were fitted with the massive and unwieldy 42-pounder cannons on their gundeck, the first 3 ships in the below listing all appear to have been armed with the 32 or 36-pounders, then 24-pounders on the middle gundeck, and 12-pounders on the upper gundeck.

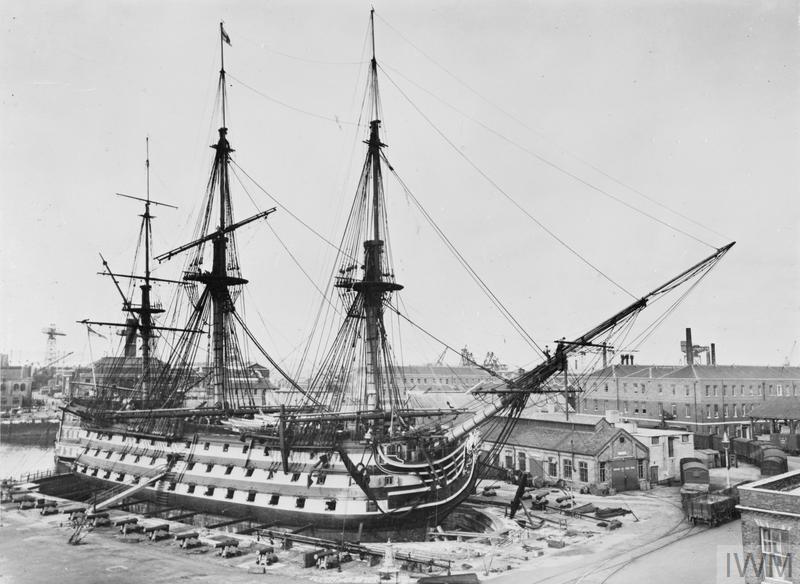

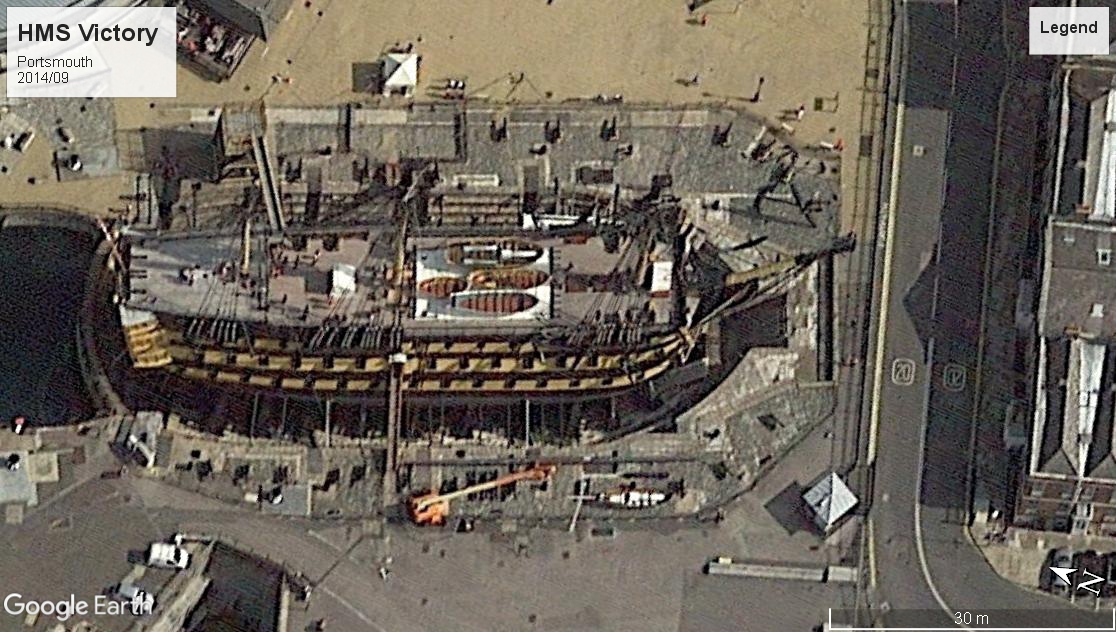

HMS Victory (1765) LOA 315′ taffrail to jibboom tip. Gundeck length: 186′. The real deal! This 104-gun ship was a queen of the battle. She was built 1756-1765. Royal Navy first-rate ships often had very long careers, with major rebuilds. She is most famous for service, 40 years after her launching, as Admiral Lord Horatio Nelson’s flagship at the Battle of Trafalgar, 21 Oct. 1805, where she led a fleet of British ships to a decisive victory over a larger, combined fleet of French and Spanish warships. Her design, by naval architect and Surveyor of the Navy Sir Thomas Slade, was based on the earlier HMS Royal George. Slade’s designs helped rectify earlier problems, where three-deckers were found to be over-gunned for their size, with dangerously shallow hulls. A slight lengthening of the gundeck gave Victory space for one more cannon on the broadside on both lower and upper gundecks. Slade produced a balanced fighting platform with good sea-keeping qualities, that was widely emulated. Her lengthy service, included participating in battles during the American Revolutionary War and the French Revolutionary Wars. In the late 1790s she was found to be worn out, and was converted to a hospital ship. This type of laying-up and conversion would have spelled the end of most warships’ active service. Not so for Victory! The grounding and loss of HMS Impregnable (98 guns) in 1798 meant that the Royal Navy required another three-decker to join the fleet. A lengthy refit from 1800-1803 remedied all deficiencies, and upgraded Victory to 104 guns. The ship’s survival, particularly during long periods of neglect in the 115 years after Trafalgar, is nothing short of miraculous. She is currently undergoing a lengthy restoration, where her topmasts and jibboom have been stored away.

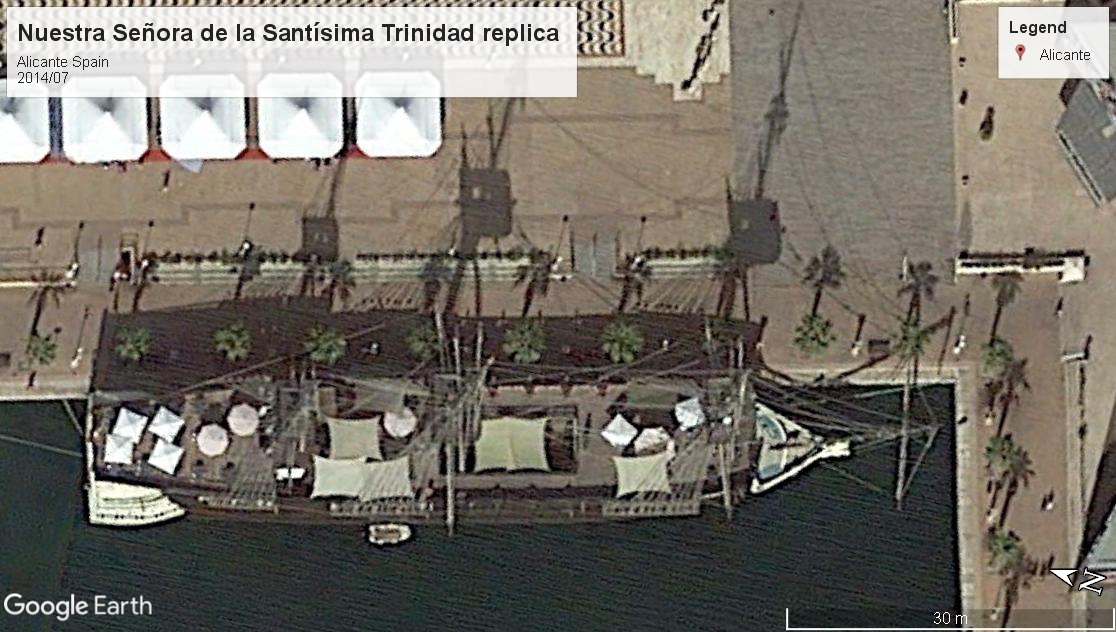

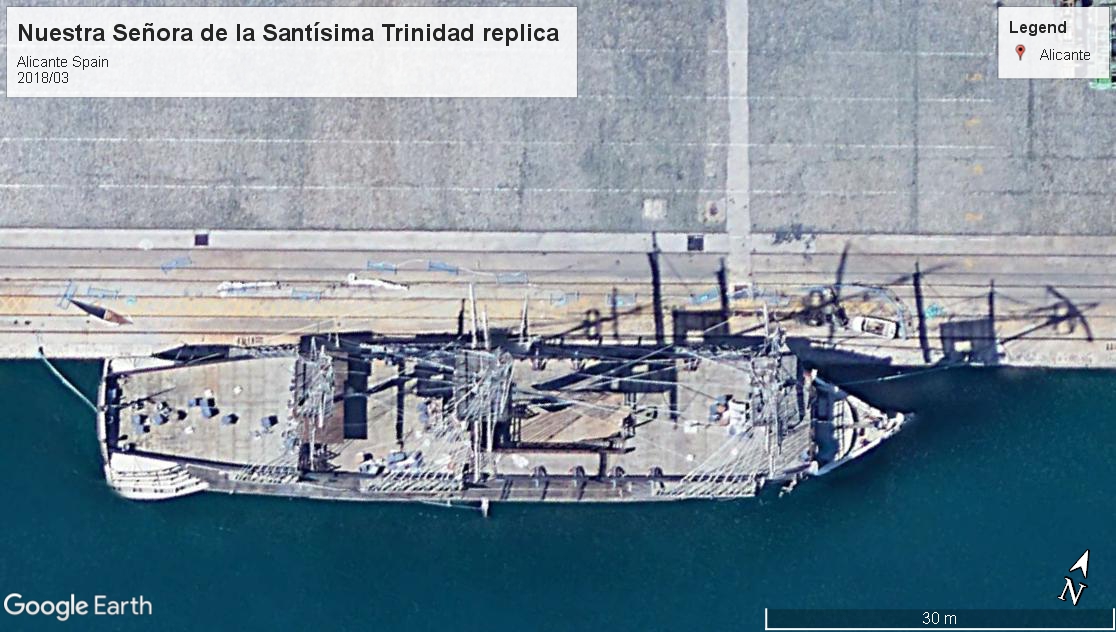

Nuestra Señora de la Santísima Trinidad replica (ca. 2005). LOA 260′ taffrail to bowsprit cap (jibboom appears to be missing now). Original ship gundeck length: 201′. This replica, located at Alicante, Spain, is of the 1769 ship, the largest of its time, which fought at several battles, and was eventually captured at Trafalgar on 21 Oct. 1805, only to be scuttled the next day in the storm that wrecked many prizes of war. The ship was originally commissioned as a 112 gun three-decker, but after several refits wound up with as many as 140 cannon, and was often described as a 4-decker, which the red paint scheme emphasized.

Santísima Trinidad, which some nicknamed “Ponderosa” due to her immense size, was technically a spar-deck three-decker, because the fourth deck was not a heavily built, continuous gundeck. Instead, a light spar-deck (or boat deck) linked the quarterdeck to the forecastle. Guns over the waist did create a continuous battery of cannon. The replica was built using the hull of a commercial vessel in around 2004, with metal girders creating a structure to hang the wooden timbers and decks off of. Reportedly, the restaurant/ship is now closed and in a state of disrepair, and images suggest the elaborate ship-rig and masts are collapsing. The replica, like the original, may be headed for destruction.

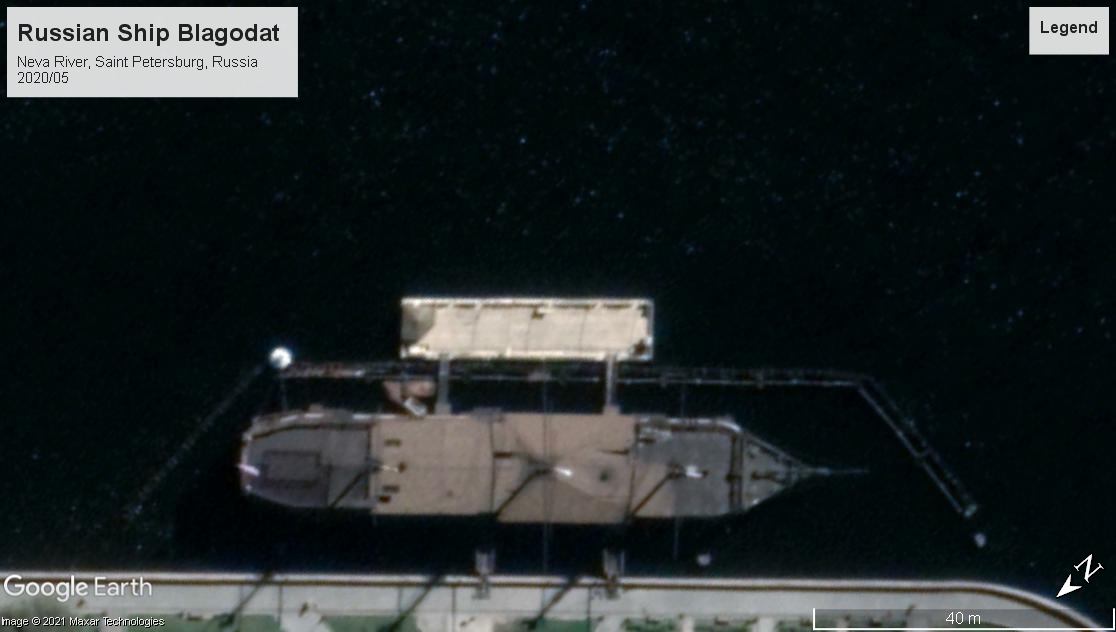

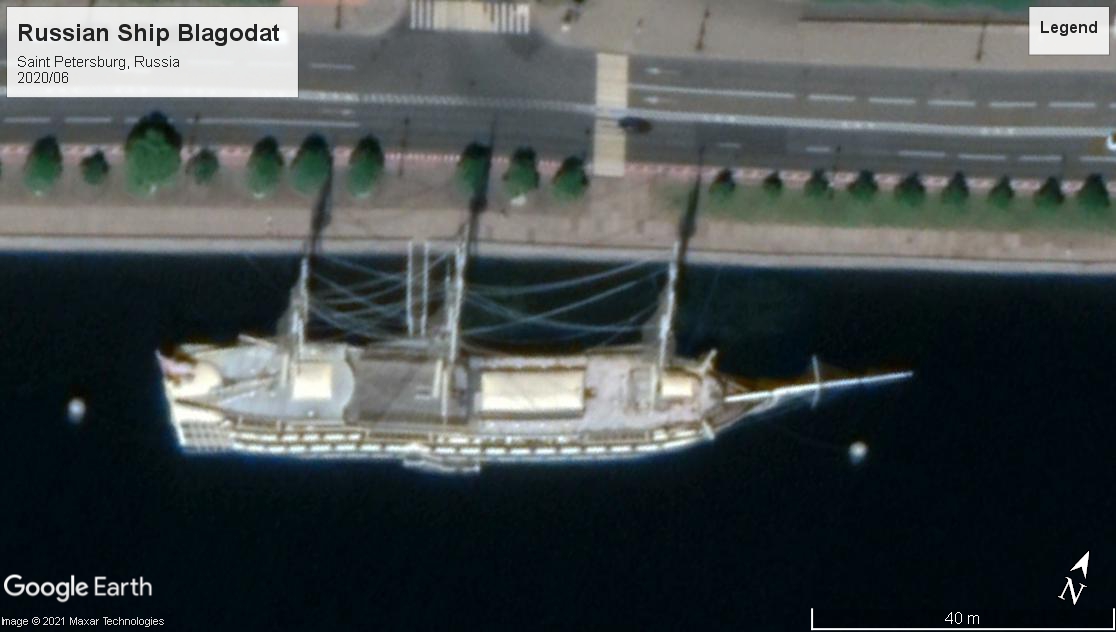

Blagodat (ca. 1990s?) LOA 325′ taffrail to jibboom tip. Original gundeck length: 198′. Another huge restaurant ship/replica of a three-decker. This is most likely a replica of the Blagodat of 1800, which served about 14 years and was Admiral Peter Khanykov’s flagship during the Anglo-Russian War. This ship was armed with as many as 130 cannon. Many features of this replica are nicely done, including the whole prospect from the bow and the tumblehome on the hull. The stern is a disappointment, and all the straight, simple lines do not appear credible for a ship launched in that era. Also, the general shape of the stern has meant the last few gunports of the lower deck near the stern quarter galleries have been omitted. Interestingly enough, the original Blagodat was reportedly based closely on the lines of a certain Spanish ship, the Santísima Trinidad!

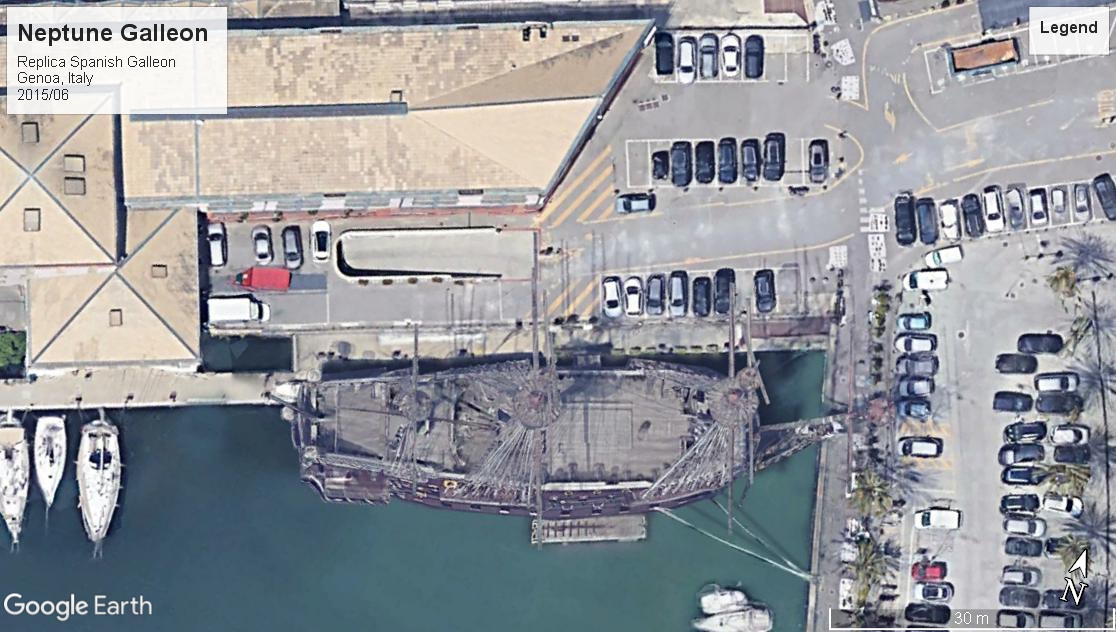

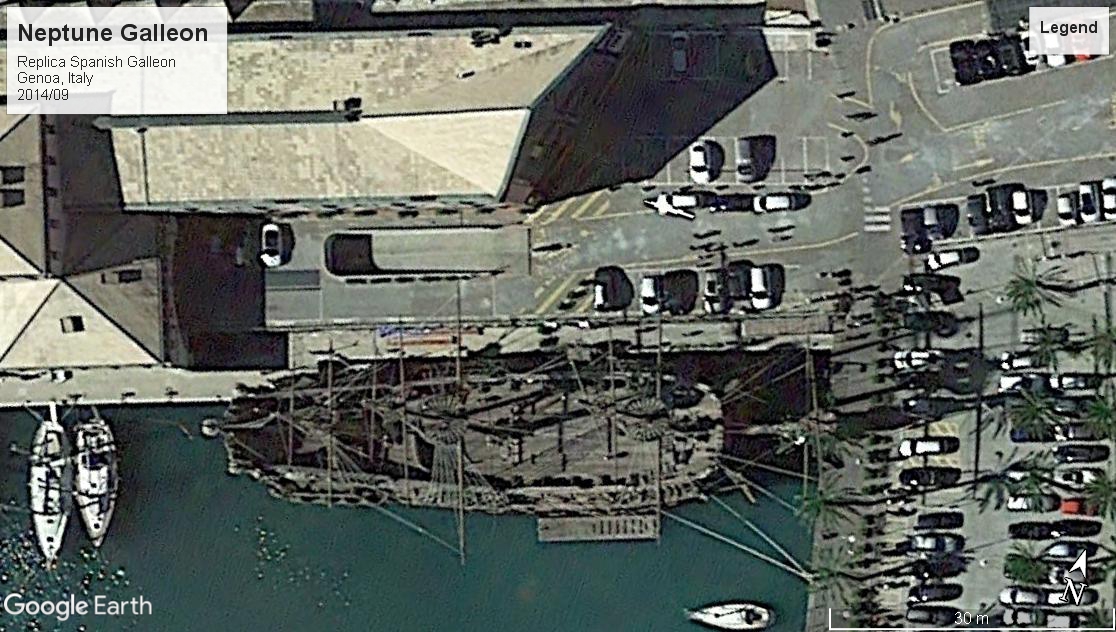

Neptune “Galleon” replica 17th Century Spanish Galleon (1986), LOA 215′ TDISP 1,500 tons. Located at the marina in Genoa, Italy, this ship was originally built in Tunisia at Port El Kantaoui, for the 1986 Franco-Tunisian adventure-comedy film Pirates. She cost 7–8 million to build, and is steel-hulled below the waterline and powered by an auxiliary engine. The hull is pierced for more than 70 gunports over three decks. While, by later standards, this is a “small” three decker, the upper deck appears to be a structural deck, and there are additional quarterdeck guns above this. It seems to us this is not an exact replica of any specific ship, and appears a good deal larger than most galleons. As noted above, Nuestra Señora de la Concepción y de las Ánimas was the first Spanish three-decker. The Neptune’s general layout has some similarities to this ship. However, the different stern galleries, the more pronounced sheer, and the general appearance of a vessel from the first half of the 17th Century, make it unlikely that this is a replica. The design seems instead to have been inspired by the great Spanish treasure galleons, but with a massively enhanced armament.

*For our purposes, we have defined the three-decker as a warship whose principal armament of heavy batteries of cannon are arrayed on three structural decks, in a more-or-less continuous row. These ships often have additional partial batteries of cannon on the quarterdeck and forecastle deck and can also have a continuous deck of lighter cannon on a spar-deck which joins quarterdeck and forecastle batteries, but is not a structural deck over the waist of the ship. We have had many disagreements about what constitutes a three-decker, or what counts towards the total number of gundecks. There were very large ships before this period, and some had a hundred or more various cannon of various types, but none that meet the criteria of a three-decker. There were also merchant ships and other warships with three decks before and during this period, but these were not armed in the way we define above. Our definition is based on scholarly works, including Dr. Frank Howard’s detailed account of the evolution of fighting ships, Sailing Ships of War; 1400-1860 (Greenwich: Conway Maritime Press, 1979). Out of interest, we would note that there was at least one design for a true four decker first rate line of battle ship: the 170-gun juggernaut that would have been named HMS Duke of Kent. A model at the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, and, reportedly, a draft plan, are all that remains of this.

** Some reconstructions show the Scottish royal ship Great Michael (1512), an enormous carrack, as a three decker, with a mix of cannon on three gundecks, one of which was an open waist, and enormous fore and after castle structures.

***HMS St. Lawrence was a vessel adapted to service on the Great Lakes. It was longer and heavier than HMS Victory, with a few more cannon. It had three long structural gundecks, but nothing above those, and a simplified stern with a single level of stern and quarter lights (windows). This massive vessel’s commissioning during 1814 effectively ended the naval war on Lake Ontario.

****In the British classification system, which evolved over the 18th Century, warships were categorized by the number of cannon they were armed with. First-rate battleships would eventually be armed with 100 or more cannon; Second-rates, 90-98 cannon. Some smaller Third-rates, which were the usual ships of the battle fleet, also, up to about the mid-18th Century, could be three-deckers. Other states in Europe employed similar systems. Also, the rating system had kept pace with the increased size of warships. A hundred years before this, in 1650, ships with more than 50 cannon were considered some of the largest.