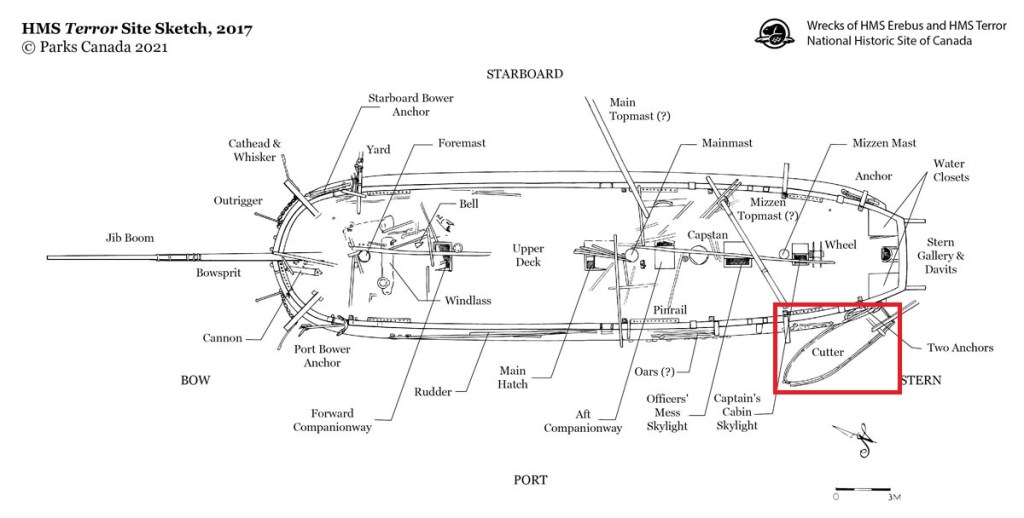

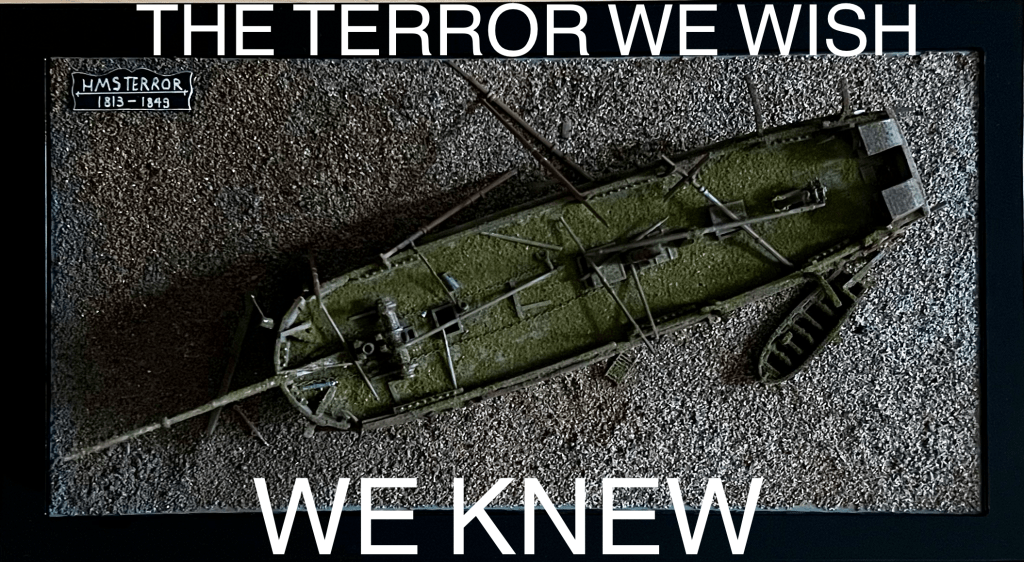

What if we could rebuild the “Boat Place” Franklin Expedition boat from its wrecked and scattered remains? In this post I will show my efforts to reconstruct the important boat I explored last week, at the same small scale as the HMS Terror wreck diorama.

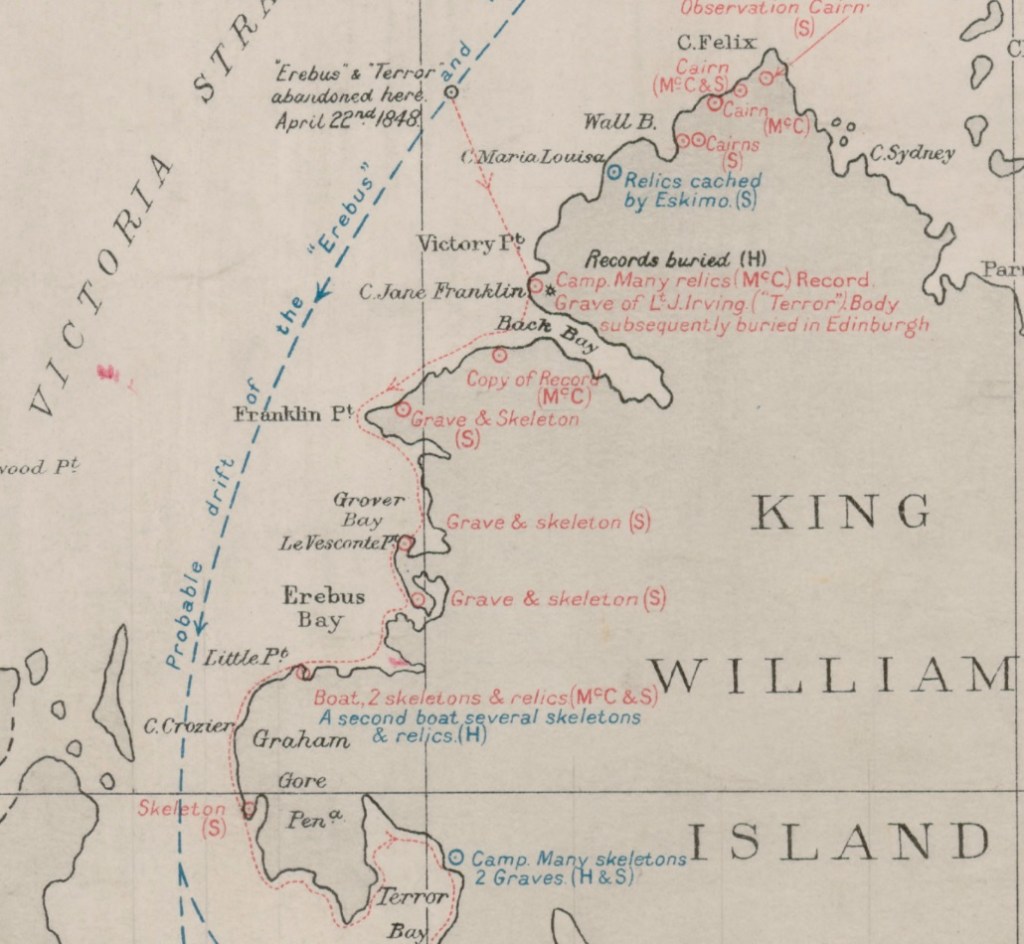

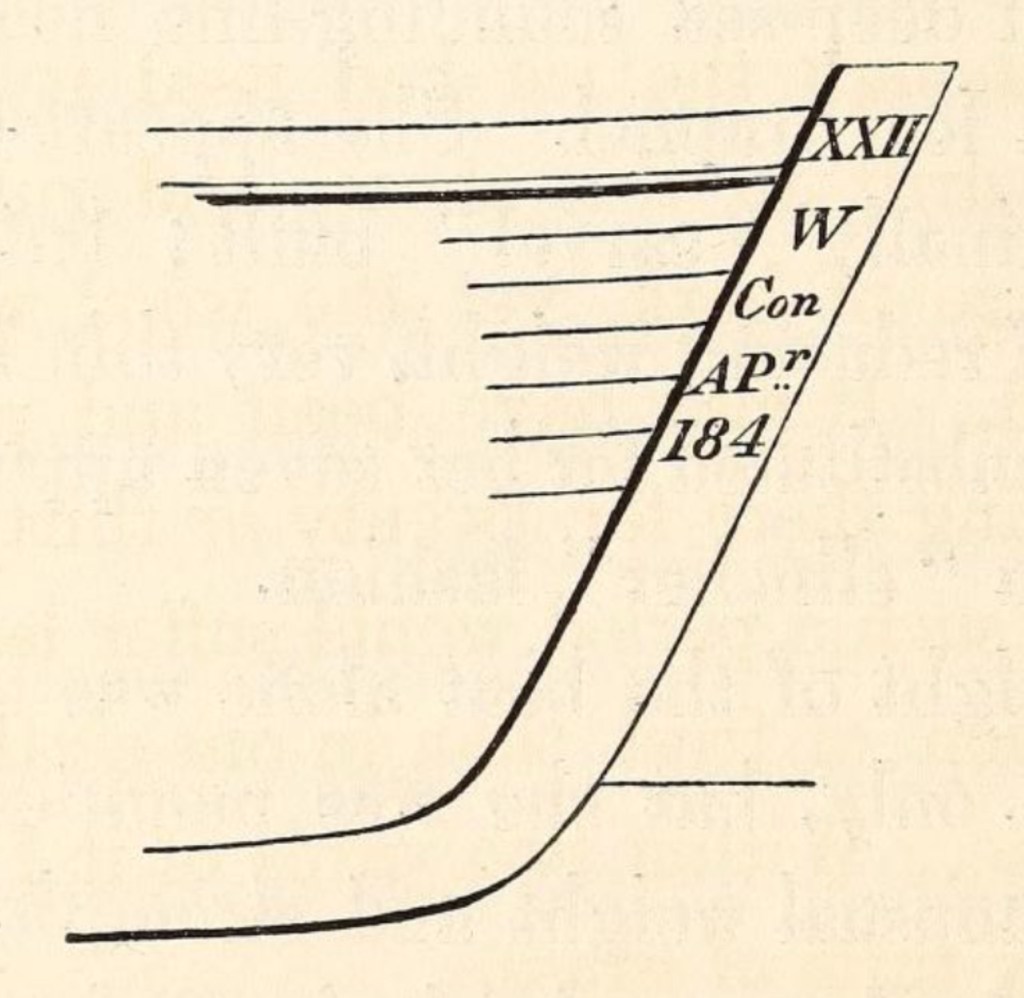

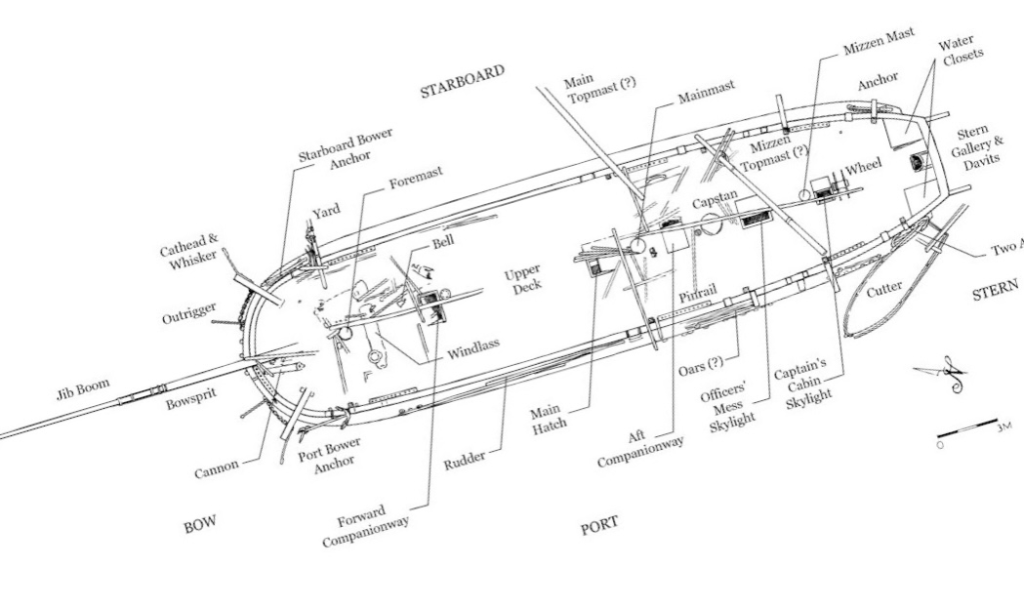

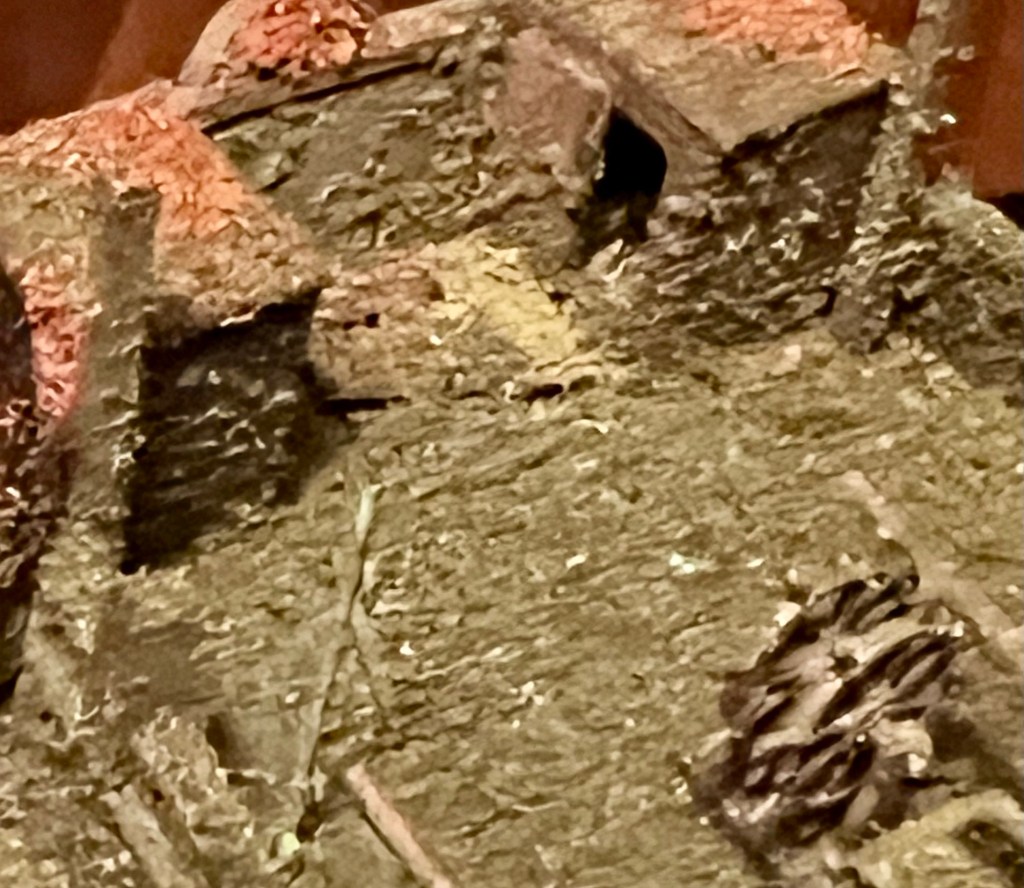

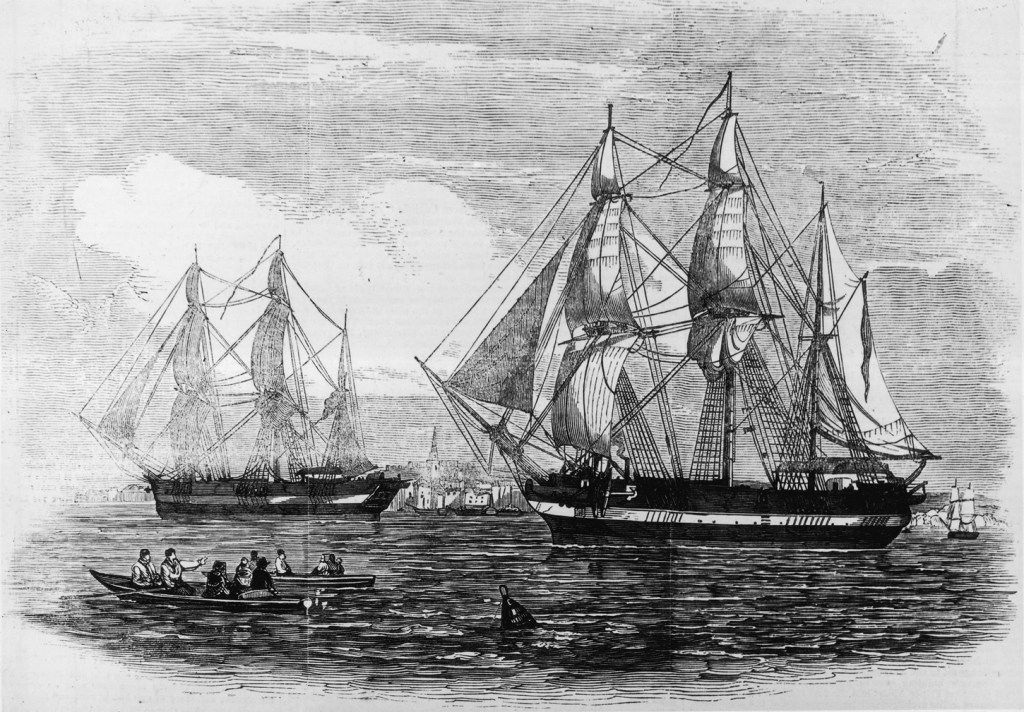

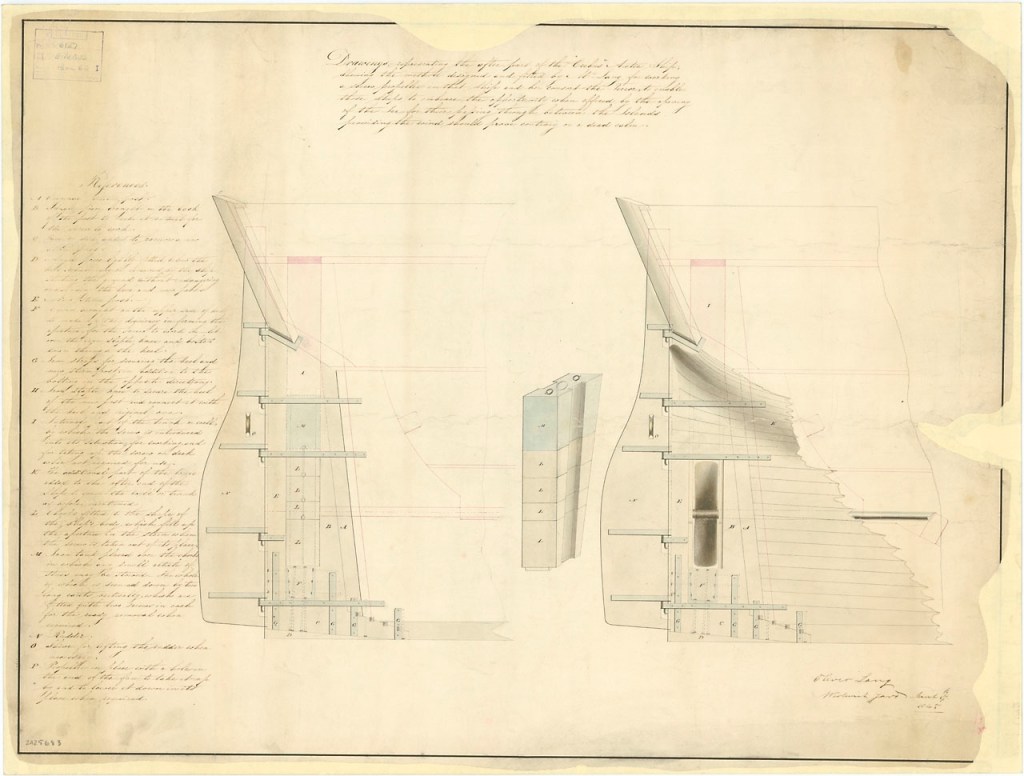

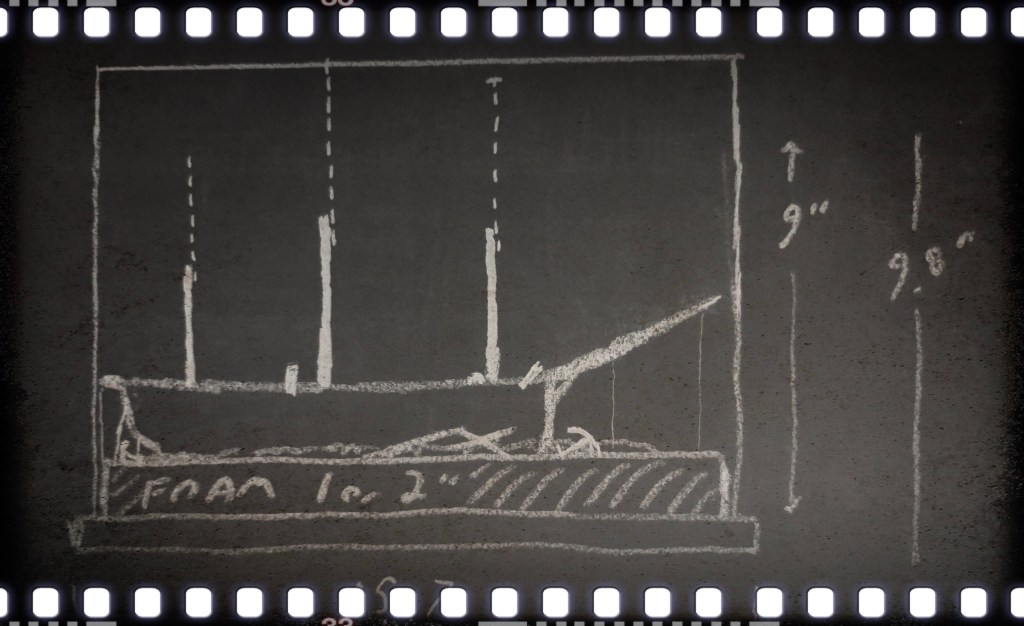

In early 2025 I set about transforming a tiny plastic model to represent the boat and sledge that searchers looking for the lost Sir John Franklin 1845 Expedition came across in 1859 on the western coast of King William Island.1 My research is summarized in the “design dossier” section of my recent post on this discovery. Stages of my build resembled some of the real modifications ship carpenters would have worked at early in 1848, as they prepared to desert HM Ships Erebus and Terror – I sawed off the old square transom (visible in the below photo) and reshaped a sharp or rounded stern using Milliput putty around a balsa wood carved-out form (later removed), and built a new curved sternpost. I added two gudgeons, on the chance that the boat could have been fitted with a rudder. As of this writing, I believe the converted boat was based on the hull of the lighter 25’ Cutter instead of the Pinnace (see below boat dimensions section for detailed information).

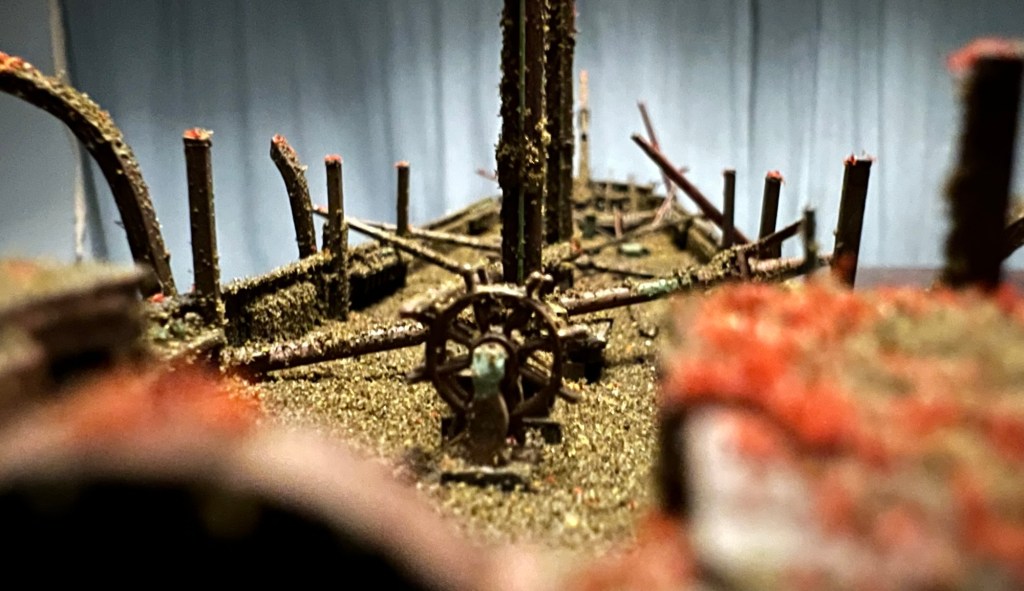

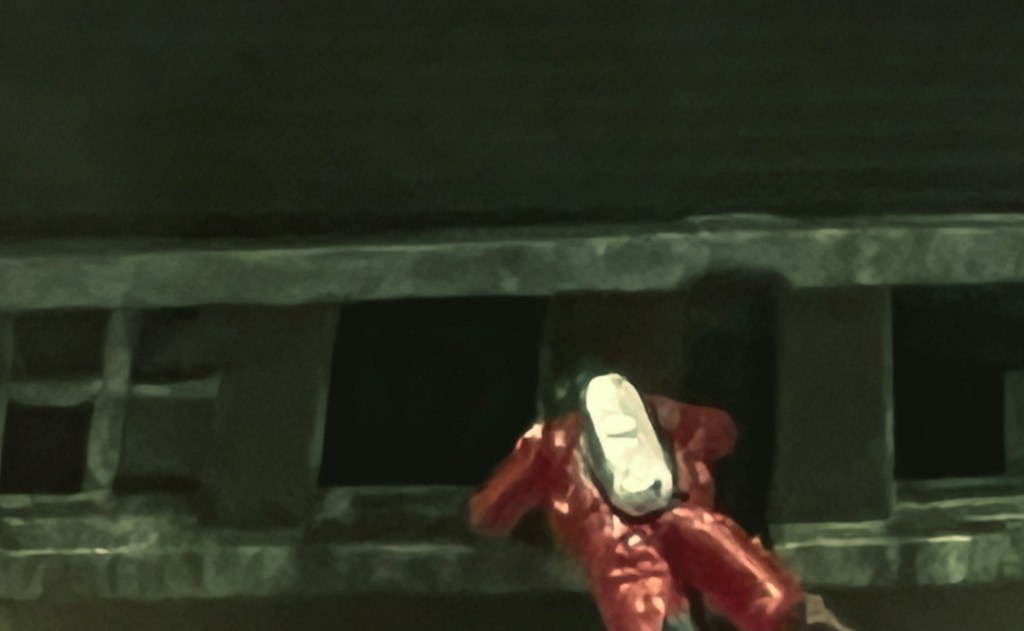

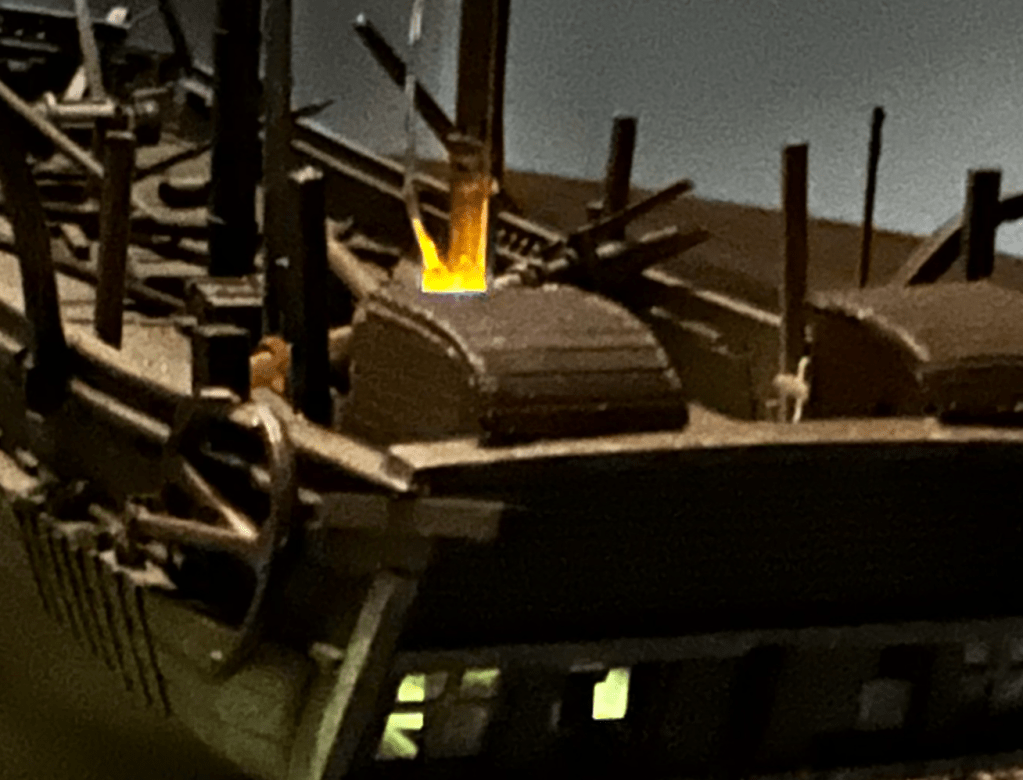

I modelled the stanchions (the two posts rising out of the hull painted two-tone black and white) to be high, with gaff jaws at their tops (as described by Lt. Hobson). Some practical tests with the model revealed that the pronounced list observed in 1859 meant that, in order for Hobson’s team to have spotted anything emerging from the high drifts of snow, that stanchion would have to be significantly taller than represented in most reconstructions. With its gaping jaws open to the sky, it must have appeared a grim marker, indeed!

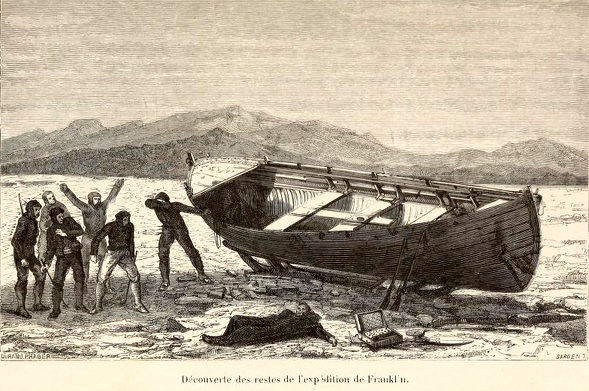

I decked over the bow and stern areas based on the Durand-Brager illustration (seen in the last post). The internal layout is similar to the whale boats that the ships carried. I like to think that the crews had a space in each boat to shelter an exhausted or ill member. A foredeck and covered stern sheets may also help explain the decade-long survival in decent condition of some of the artifacts that Hobson and McClintock discovered in the boat.

The gunwales were drilled for the thowells – tiny metal rods. I believe there was no washstrake boards, so I spaced the twenty-four thowells to support a washcloth that wrapped around the hull between the posts. Hobson noted these thowells (National Maritime Museum artifact AAA2143) were doubled up to assist the paddling. I paired them to create four rowing positions a side, and ran a rope along the top of the thowells, which the washcloth would have been rove into along its top edge.

Artifacts currently placed in the model hull include six modified oars (cut down with add-on blade extensions), the sheet block (AAA2198), the folded-up lead sheets (AAA2280), and some sailcloth that could be the awning or the washcloths (AAA2144). Basic pieces of boat equipment, such as two masts, and a rudder, have never been found. I have added a mast step amidships, in case information or evidence of these details turn up. When under sail, the boat would likely have carried lugsails on its two masts.2 I hope someday to model the ice grapple/anchor encountered by the searchers. The bewildering assortment of personal items, cutlery, packets of chocolate, and human remains have not been represented.

This boat and sledge combination may look unwieldy, especially when compared to the supremely well-adapted Inuit equivalents: animal hide boats (Umiaks) on sledges built of lightweight organic materials. But in 1859, Francis Leopold McClintock – a masterful long-distance sledge traveler – seems to have been impressed by the lost crews’ efforts at lightening it.

As with so many of the specifics about the 1845 Franklin Expedition, we continue along our own voyages of discovery. This is not the first interpretation of the Erebus Bay boat, nor will it be the last. I have created a sad miniature of that “melancholy relic.” [Read more in the Appendix below for technical info about the boats and sources]

Appendix-JC Ross (1839) and Franklin (1845) Expedition boat types and sizes and notes: