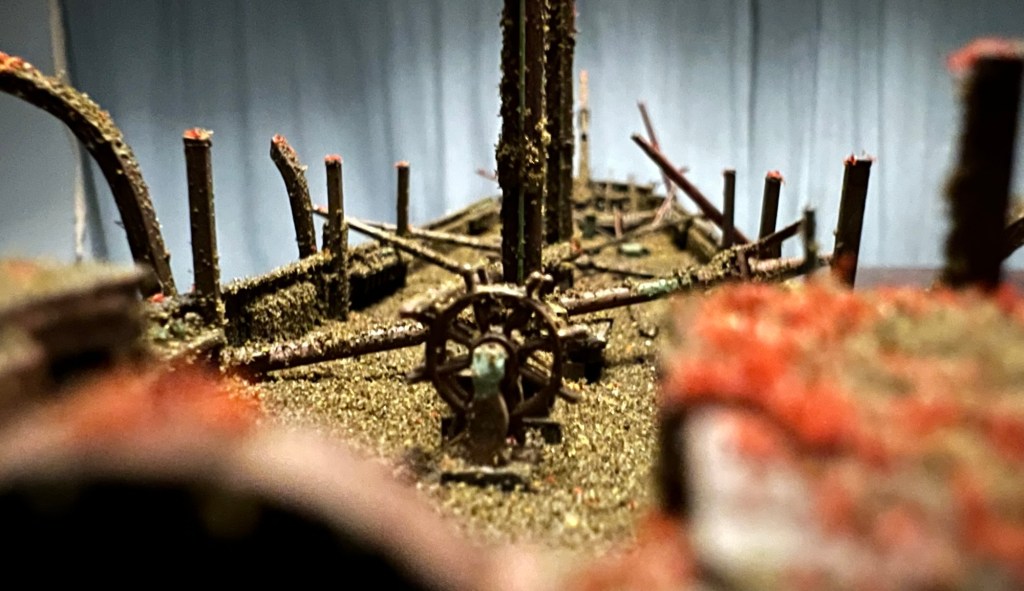

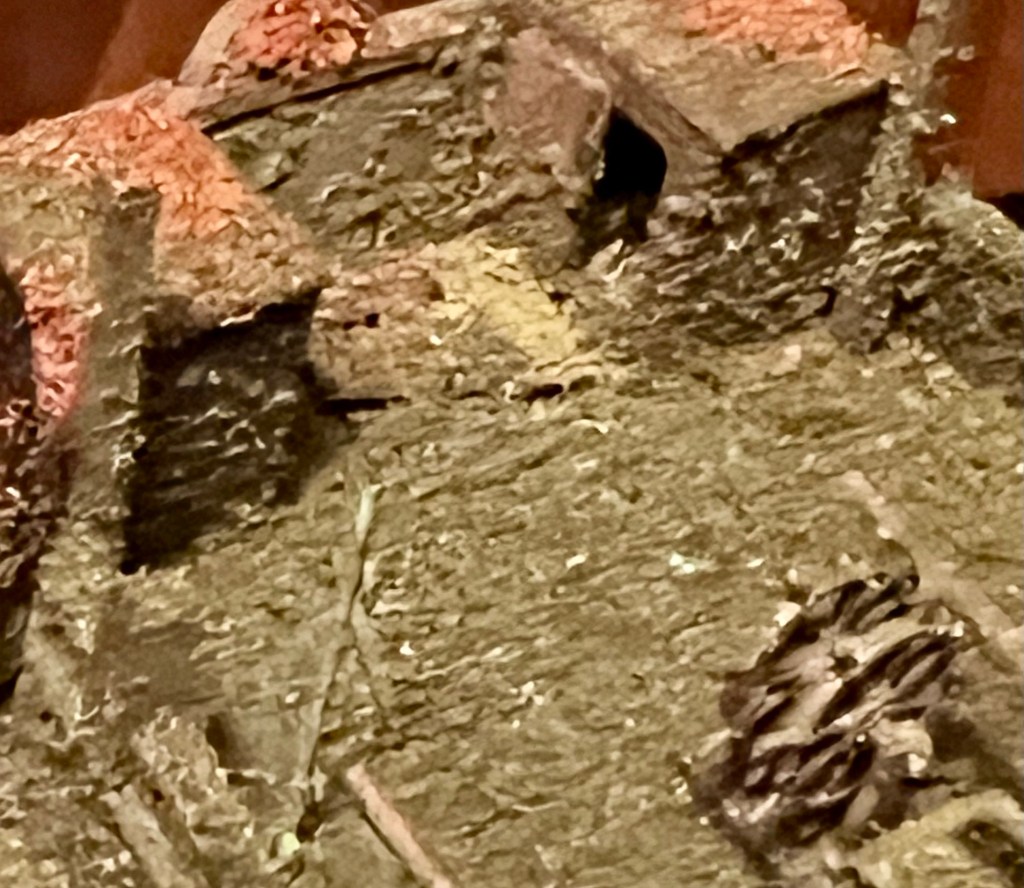

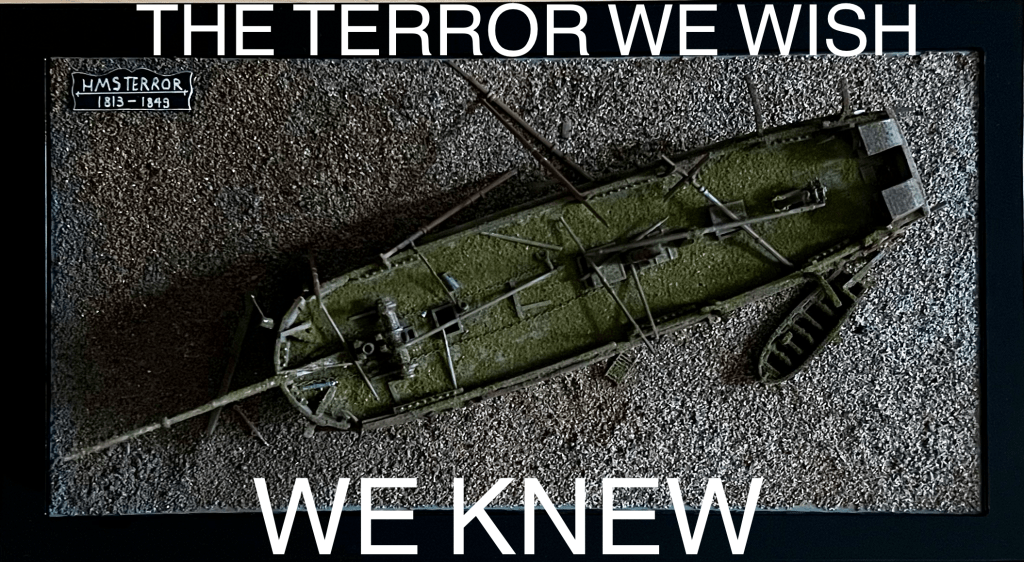

I recently wrote “Could I contemplate a scenario where new information would compel me to get back to work revising my Terror diorama?”1 Well, that situation happened almost immediately! In this post, I focus on what may seem a minor discovery – HMS Terror’s 1845 screw propeller. I argue that it is one of the outstanding finds at either Franklin Expedition wreck site. I will explore the history of this well-preserved artifact and situate it in a revolutionary program of naval ship design. I will conclude by showing how I incorporated the propeller into my diorama of the wreck site.

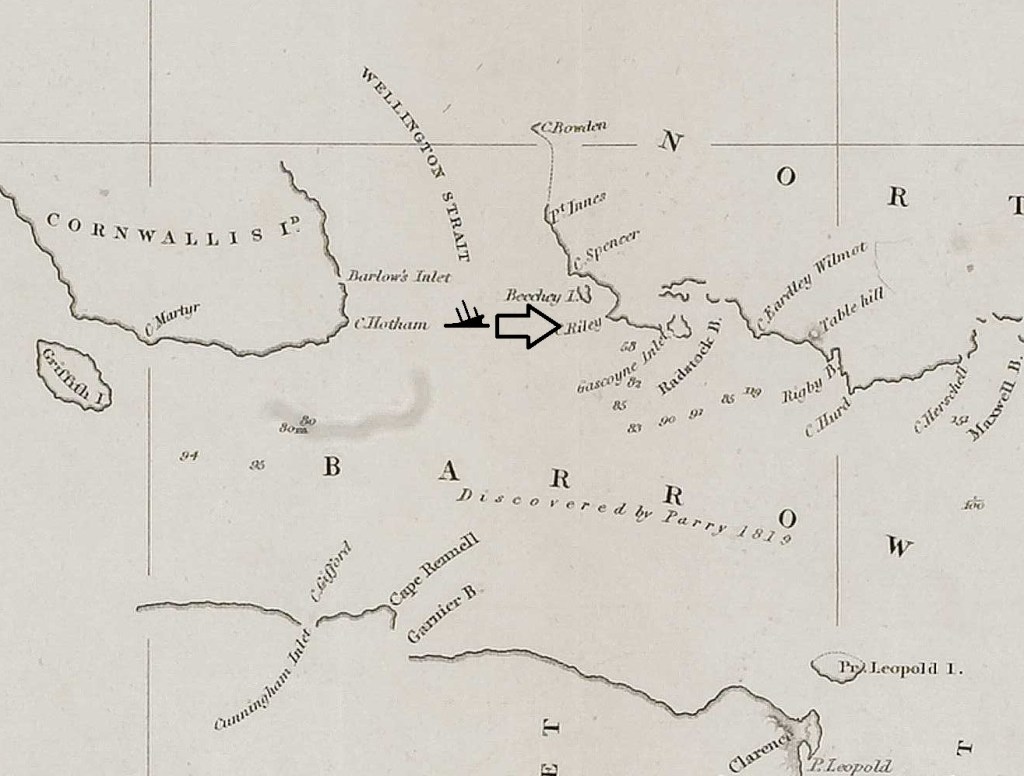

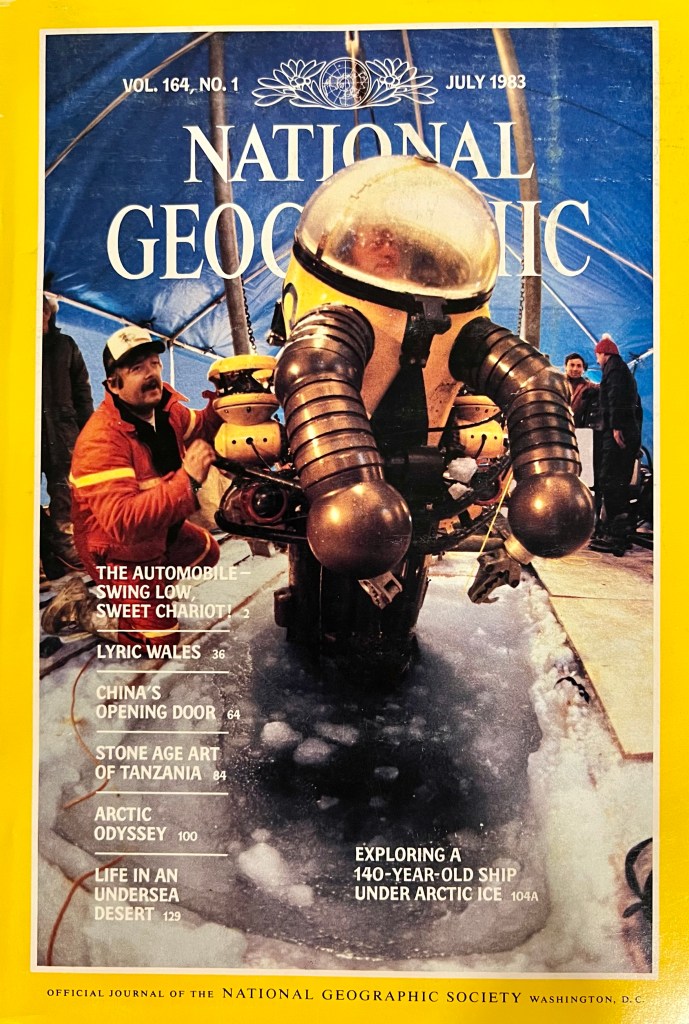

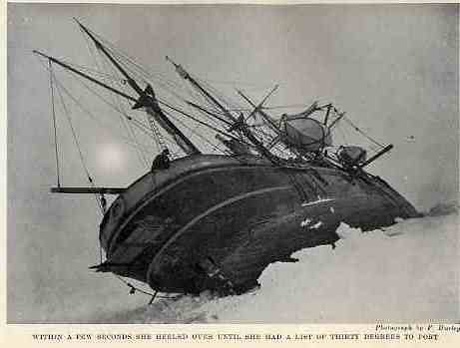

One hundred and eighty years ago, a visitor to Her Majesty’s Dockyard, Woolwich, near London, would have been treated to a memorable sight: one of Queen Victoria’s warships – under refit to explore the Arctic – was up on the stocks in dry-dock. This was one of a pair of bomb vessels (a type of specialized mortar-armed bombardment ship) which had been converted years before for polar missions. These tough ships had more than proved their mettle during James Clark Ross’s wildly successful expedition to Antarctica. Now the duo – each painted in severe black with a broad white strake stretching along the hull – had been selected for a new “Discovery Service” mission, to be commanded by Sir John Franklin: Complete a Northwest passage across the top of North America. Walking around the dock to the ship’s stern, that visitor would have seen something unusual: a strange cavity low down at the swollen stern post. This was just inboard from an enormous rudder. The hole opened clear through to the other side, like some casemated gun embrasure. Set into this void was a metal monstrosity: A cylindrical shaft with two broad blades twisting away from it. The visitor may have recognized this as a screw propeller – a marvel of the age. When coupled by a long shaft to a steam engine mounted in the bowels of the ship, the rotating screw could propel the vessel – all without a single sail of the lofty three-masted rig drawing a favourable breeze. If that same visitor had returned later, they may have felt the dupe of some trick: the machinery could have completely disappeared, leaving the man-sized hole. As if by some further sleight of hand, the whole cavity could have also appeared closed up, with only a faint rectangular outline now in evidence. What category of navy ship was this anyways? A sometimes-steamer with a propeller that unscrewed right off?! Indeed, here was something completely new: The first auxiliary screw-propelled polar exploration vessel!

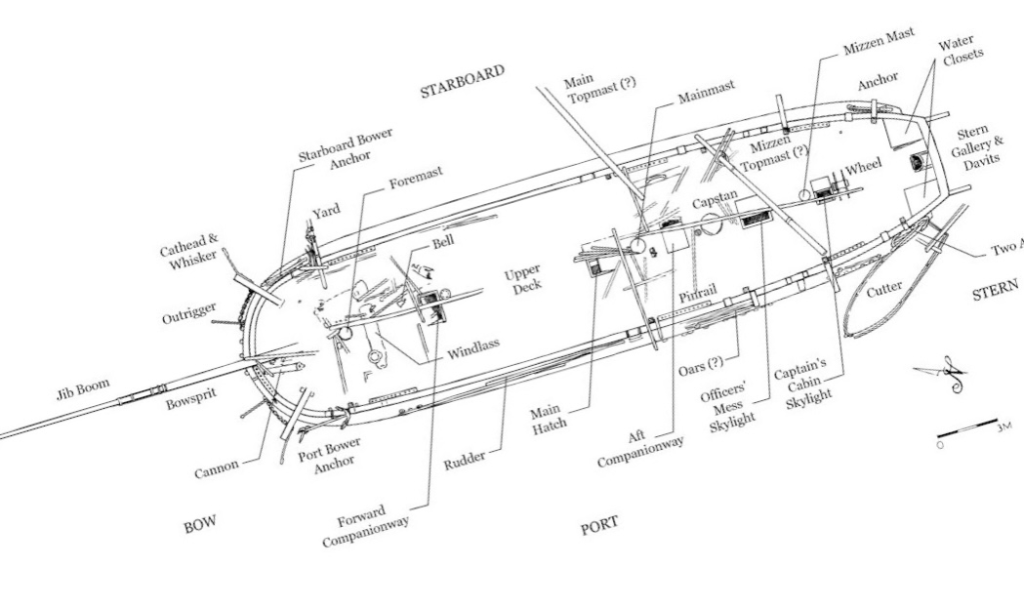

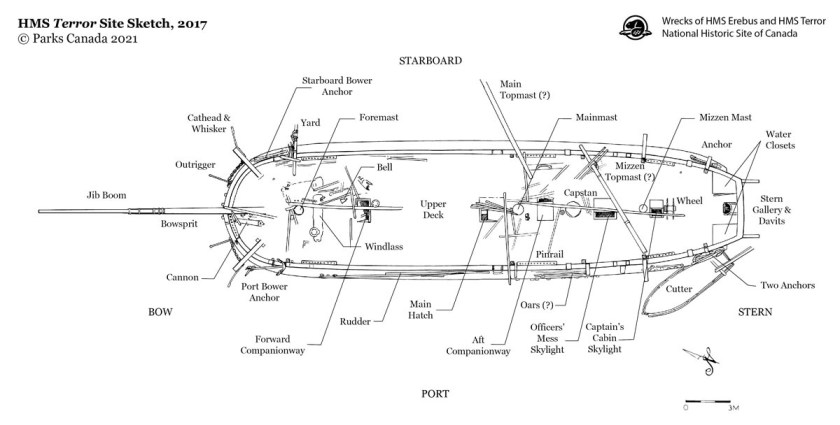

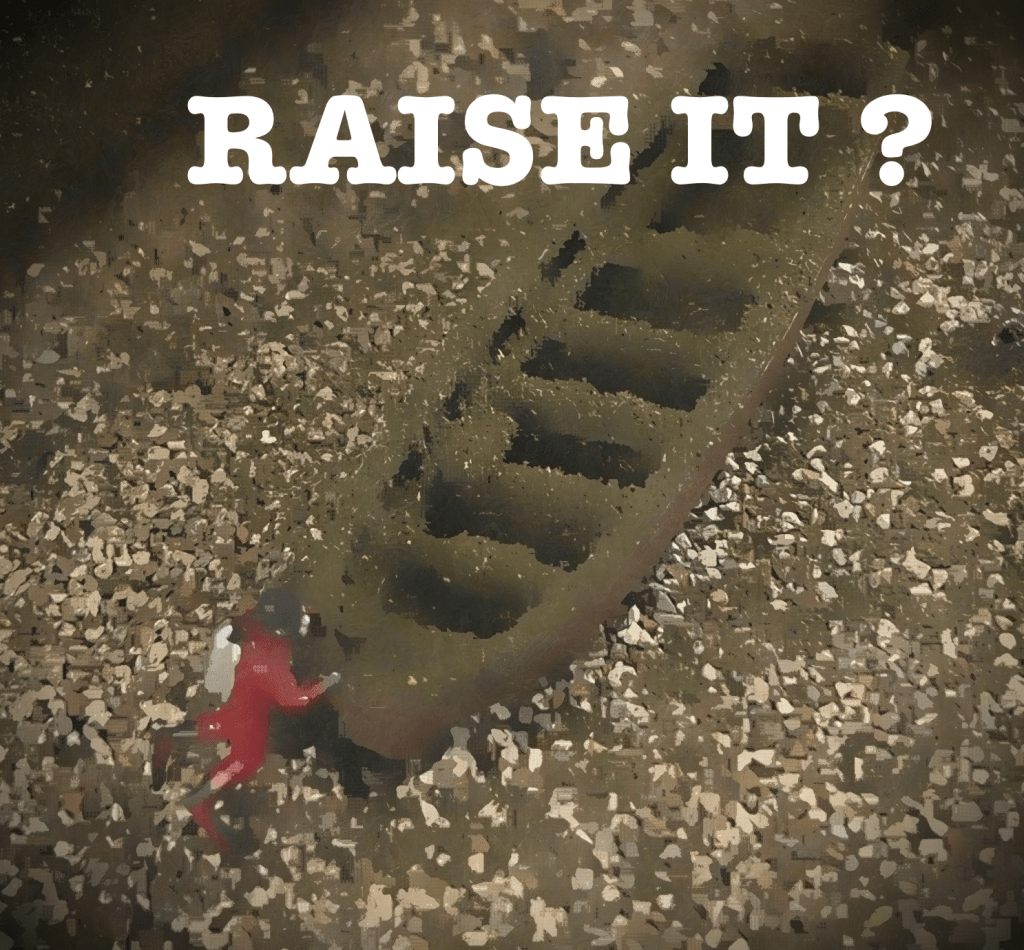

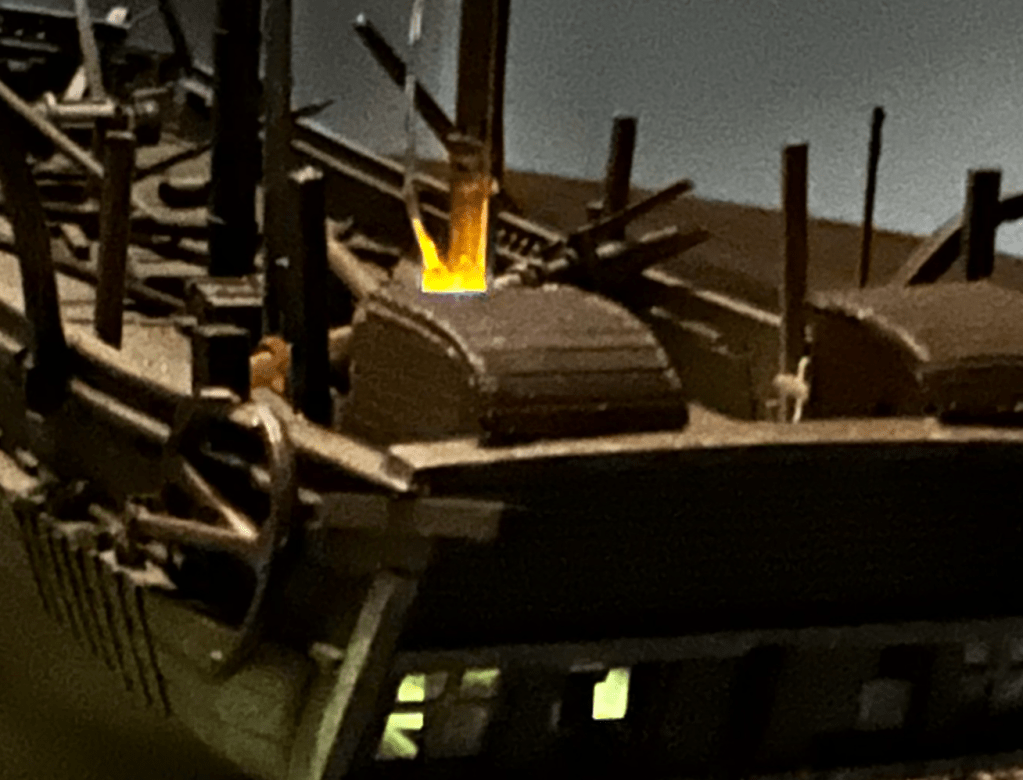

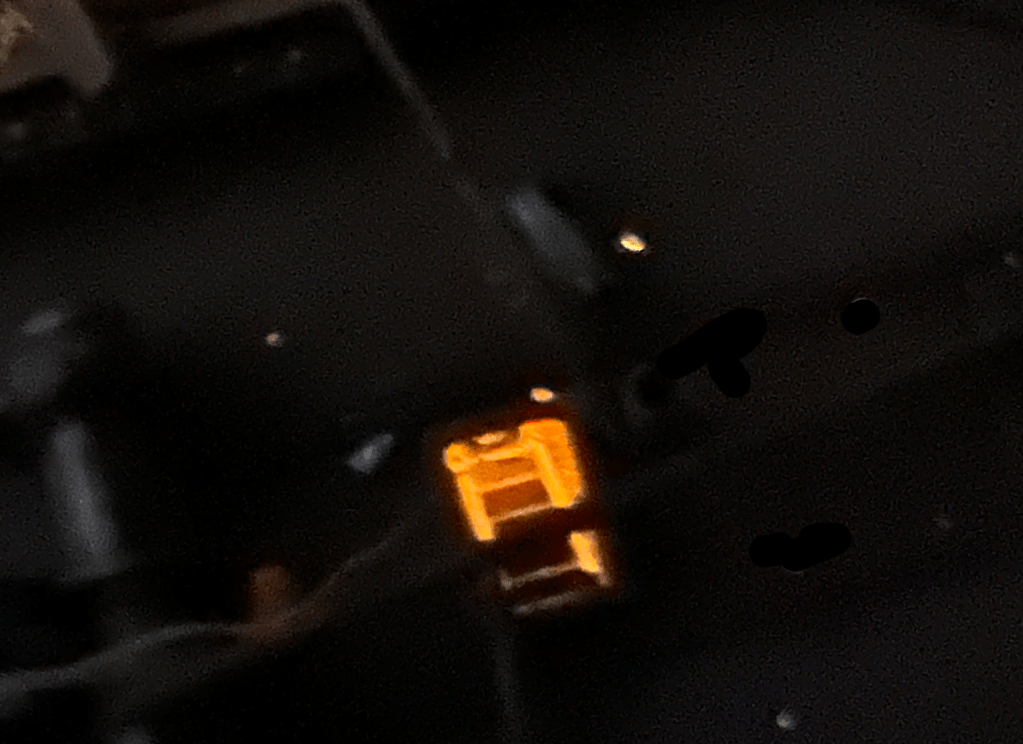

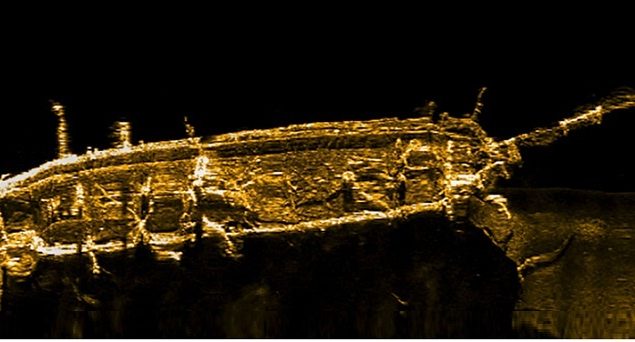

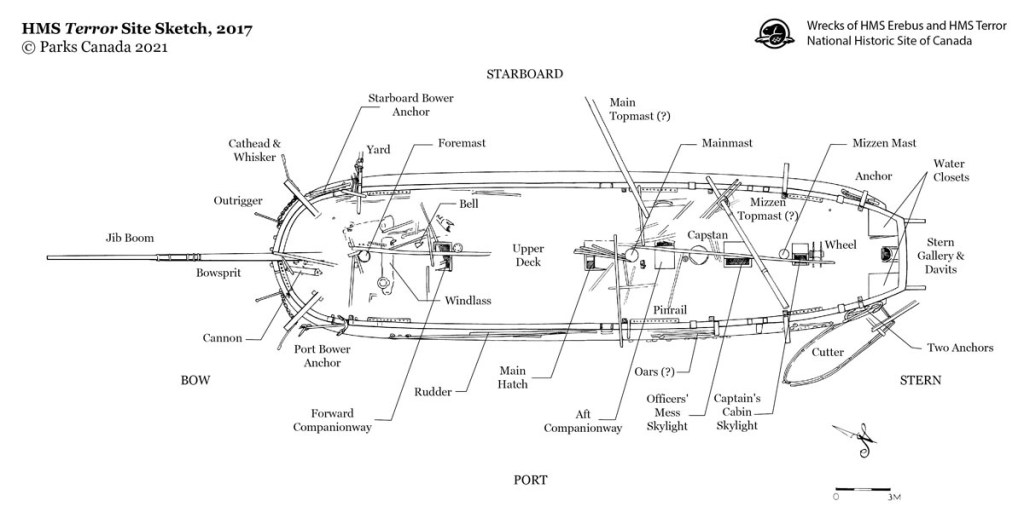

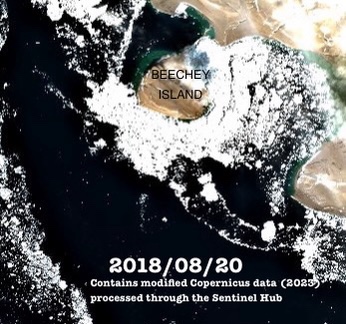

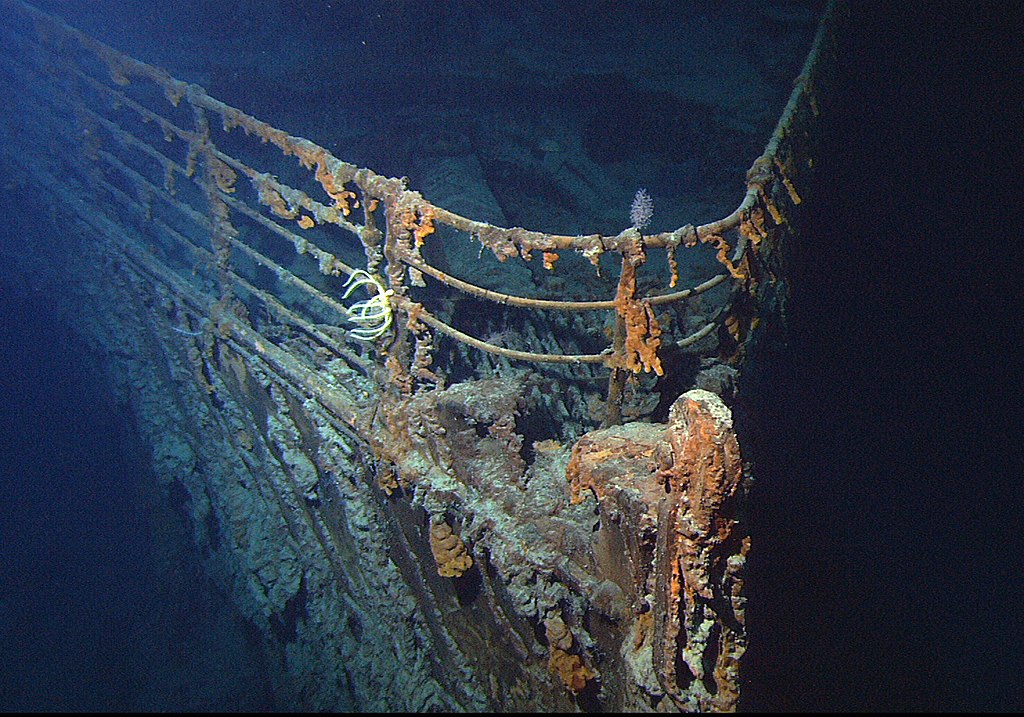

Early this year I was searching for information about the 2024 Parks Canada program of archaeology on the Sir John Franklin shipwrecks, HM Ships Erebus and Terror in Nunavut, Canada. Instead, I stumbled upon a new post “Anchors and Propellers” by Franklin Expedition scholar and veteran searcher David Woodman on his site: Aglooka.2 This update assembled interesting information about the ships’ complement of anchors, and also their propellers. Reading on, I encountered a previously unpublished image from the Parks Canada Underwater Archaeology Team (above). I was stopped dead in my wake! Here we see Terror’s screw propeller, installed in its aperture! With this photograph, we have the first visual confirmation that a marvelous piece of Victorian maritime technology has survived relatively intact after more than 175 years of immersion at Terror Bay.3

This simple two-bladed screw is one of the most important artifacts existing at either Franklin shipwreck site. The Commemorative Integrity Statement relating to this National Historic Site of Canada specifically identifies the marine screw propulsion as a character-defining aspect of the sites, demonstrating the 1845 technological innovation of the Expedition.4 From the waterline up, both ships looked much like they had during J.C. Ross’s expedition to Antarctica (1839-1843). Erebus and Terror were also not the first ships with an auxiliary steam engine to go north: In 1829 Ross’s uncle, Sir John Ross, had taken Victory north with an experimental – and mostly useless – steam engine.5 However, the idea of fitting a removable screw propeller into a Discovery Service exploration vessel was truly original. The suggestion came from a superstar in polar exploration. As Dr. Matthew Betts relates in his book HMS Terror – The Design, Fitting and Voyages of the Polar Discovery Ship, the seasoned Arctic explorer Sir William E. Parry – who now had an official role in investigating the optimal methods of steam propulsion in the Royal Navy – believed that the new propulsion technology could give vessels operating in the Arctic Archipelago a big advantage: The ability to navigate tight passages free from any dependence on the vagaries of the winds.6 Having auxiliary steam propulsion available to the Expedition captains could help force a constricted passage, position the vessels to better meet the rigors of overwintering in ice (for example by allowing them to get to a safe harbour or a more sheltered section of coast), or get them clear of an immediate hazard, such as an errant iceberg or a perilous lee shore. Parry’s experience commanding similar vessels in the Arctic provided him with an invaluable perspective on how screw propulsion could support this new attempt to transit the Northwest Passage. The Admiralty endorsed Parry’s idea.

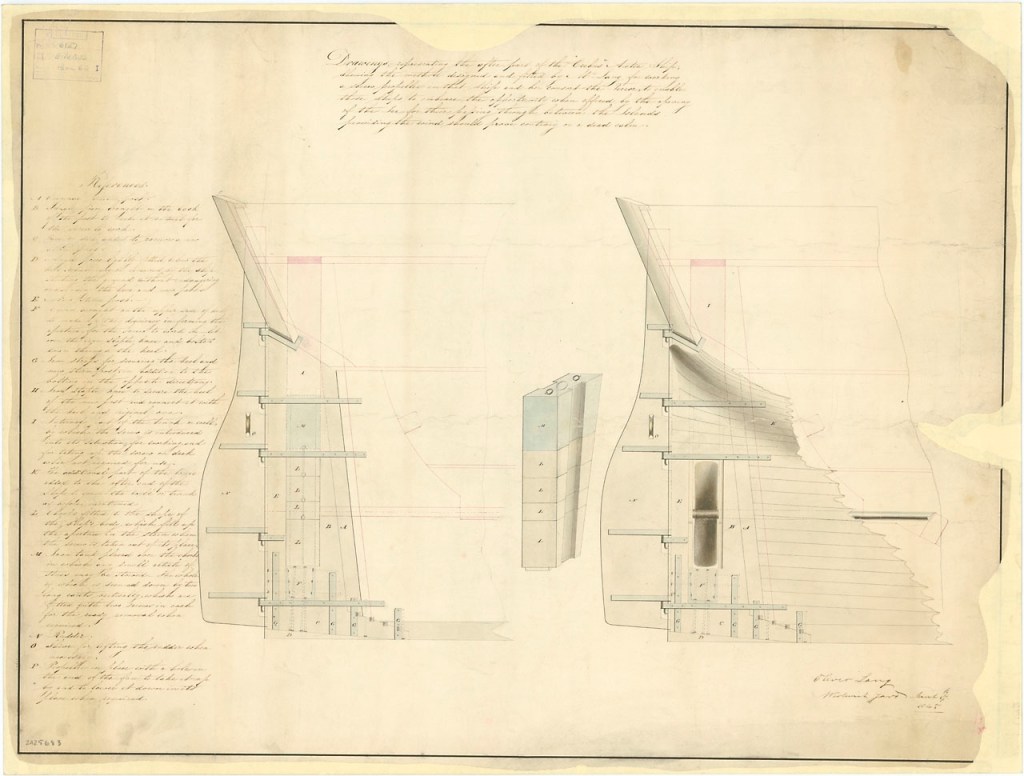

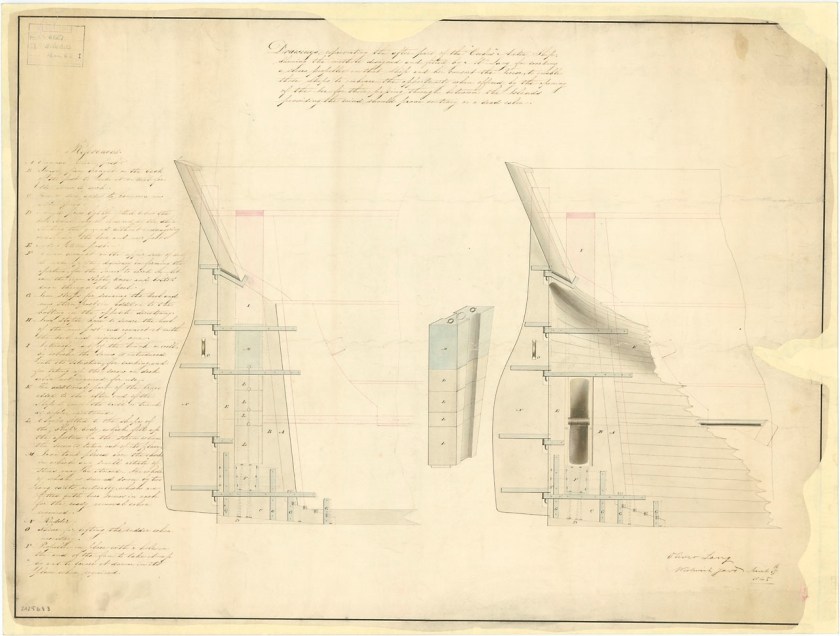

Oliver Lang, Master Shipwright at Woolwich, was responsible for working up a technical plan to meet this new requirement. A half-century after he had begun drafting designs, he remained at the forefront of marine technological innovation. During the early 1840s, the military strength of the Royal Navy still rested on the line of battle ships of the sailing navy, those wind-powered “wooden walls” whose broadsides of cannon had allowed Great Britain to dominate the World’s sea lanes. Lang applied new technologies to both mercantile and Royal Navy vessels. He strengthened the basic structure of warships, packed their hulls with new innovations, and enhanced crew comforts onboard, especially to improve lighting and circulation of air. His innovations helped equip the fleet with larger, stronger, and safer warships. He had recently turned to incorporating steam technology into his designs. There had been experiments with steam engines and, since the early 1820s, some small naval units had been propelled by paddle-wheel. The Admiralty was conducting a series of trials of steamers to test a variety of newly-designed screw propellers against paddle-wheel propulsion.7

Lang’s own treatise Improvements in Naval Architecture (1853) is an important source for understanding his remarkable career. In his own words he “Arranged and fitted the first SCREW propeller to ship and unship in a TRUNK, so as to be taken up on deck in the ships “Erebus” and “Terror” on the late Arctic Expedition for Sir John Franklin.”8 The years 1844-46 were a busy period for Lang, which saw him embark on an ambitious campaign of propeller experimentation, design, and installation. He had first improved upon Rattler’s recently-installed propeller by re-rigging this steamer with a new mizzen mast, which could be used to lift the propeller in its frame straight upwards through a slot which communicated with the steamer’s weather deck. This allowed the crew to ship and unship the propeller, without specialized dockyard facilities.

While building the large steam frigate HMS Terrible (1845 – fitted with paddle wheels), he moved on to designing and fitting his first complete naval propeller assembly. HMS Phoenix (1832) was modified from a paddle-wheeler to a screw steamer. Most of the essential elements of a Lang screw-fitted stern were now in place: propeller aperture, screw propeller, false stern or rudderpost behind the sternpost, a passage for lifting the screw upwards to the weather deck, and the means for lifting it out. The modifications to the Phoenix were underway when he got the “rush order” for the work on the two Northwest Passage exploration vessels.9

The main difference in modifying Erebus and Terror with auxiliary propulsion (with much less powerful steam engines converted from railway locomotives) was that the screws would only be fitted during occasional steaming, and chocks would fill each ship’s propeller aperture most of the time. This filler needed to streamlined into the lines of the hull to not weaken a vulnerable area, and to continue to guide the flow of water aft to the rudder. Lang’s other designs had the propeller fitting into its own iron frame, with the entire assembly lifted through a narrow passage to the deck, or lowered back in place. Erebus and Terror, by contrast, had rails that guided the propeller, which was lifted on its own.

Phoenix was ready in February 1845, and Lang moved to the design of HMS Niger, which would go on to be used in a more balanced round of evaluations of screw-versus-paddle propulsion (with Niger and Basilisk a closer match than Rattler and Alecto had been). During April, the Franklin ships were modified with their unique combination of adapted railway steam locomotive – installed deep down in the after hold – and auxiliary propeller. Woolwich dockyards had its own highly specialized engineering facility – the “Steam Factory” – with the equipment and docking slips to install the new steam systems. Lieutenant Henry T.D. Le Vesconte of HMS Erebus provided a contemporary description of the work. Writing to his father on 2 April 1845 – after he discussed the excellent prospects for promotion that would come his way by serving with the Franklin Expedition – he noted: “The ships are at present in dock where we are rigging each and stowing them while the shipwrights are altering their sterns by bracing on abaft the stern posts an large mass of timber of the same thickness in which to work the screw propellers the engines will be put in next week[…].”10 After the engines and propellers were tested, and the ships finished provisioning, the Expedition departed from Greenhithe, 19 May 1845. (Continue to explore Terror’s screw propeller on the next page)