HMS North Star was an outstanding ship with a most fitting name. Like her namesake, the Pole Star, she guided mariners back home from the edges of the charted World. Though overshadowed by the lost Sir John Franklin 1845 Expedition ships Erebus and Terror, and the famous vessels searching for them, Resolute and Investigator (to name two), North Star did exceptional work in the Arctic.1 Her transformation from fighting corvette to expedition depot ship may not seem as interesting as the refits those other ships received. Actually, the 1849 rebuild created an Arctic juggernaut – a vessel tough enough to withstand collisions, groundings, ice “nipping,” and general Arctic pummeling during two missions over the course of five busy years. When all other ships had to be abandoned, North Star brought the Sir Edward Belcher Expedition home – saving the Franklin searchers!

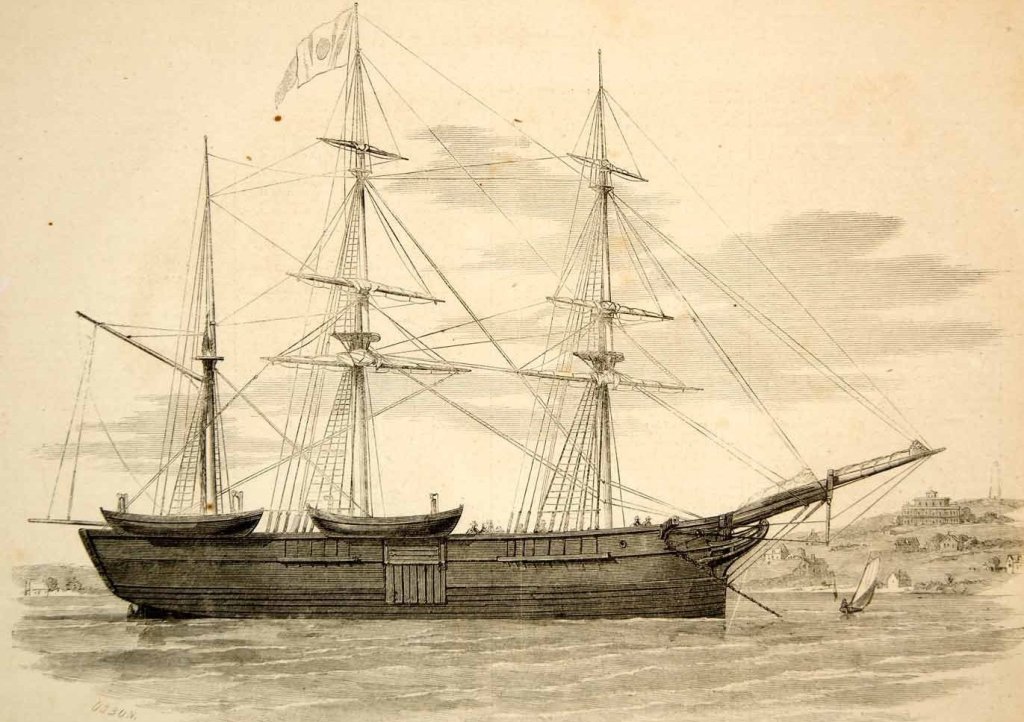

HMS North Star was launched at Woolwich dockyard in 1824 and completed in 1826, to a trim design – an Atholl class corvette – that we explored in a recent post.2 Like other “Donkey Frigates,” she spent much of her career in distant waters. “Donkey Frigates” was a contemporary term for a small frigate-like corvette performing the roles normally taken on by larger, more expensive to operate warships, such as Leda class frigates. A fine record of the 1826-1848 events of North Star exists at the “Index of 19th Century Naval Vessels and some of their movements” at RootsWeb. Her early service came as a member of the West African Squadron – patrolling to suppress the Atlantic slave trade. This was followed by participation in two of Britain’s imperial wars of the mid-19th Century.

A member of Sir William Parker’s fleet involved in the First Opium War (Anglo-Chinese War), she was present at the signing of the Treaty of Nanking in August, 1842. During 1845-46 North Star operated around New Zealand during the Flagstaff War, contributing shore parties that fought in battles against Maori warriors who were resisting the recently-imposed colonial regime. At the same time, at the frozen top of the North American landmass, Sir John Franklin and his two ships – making their bid for completing a Northwest Passage – were wintering at a location that would figure large in North Star’s subsequent history: Beechey Island.

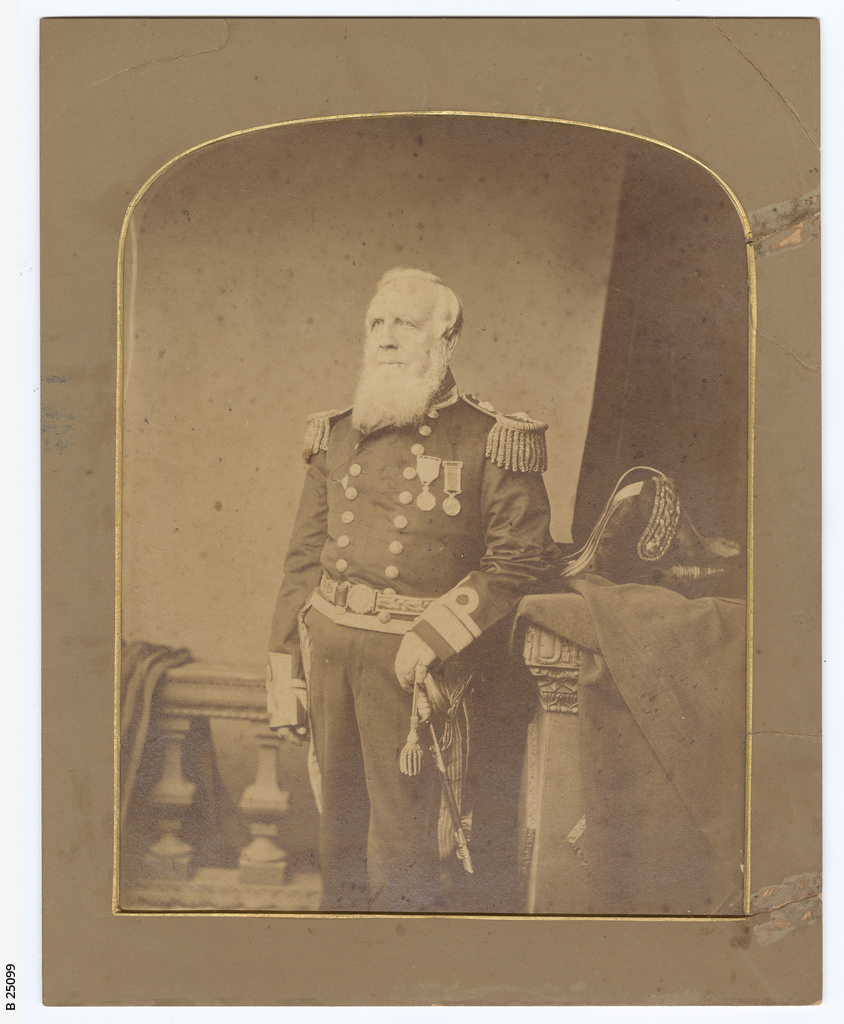

Three years later, public concern about the condition of the missing Franklin crews was reaching fever pitch. North Star was ordered north to rendezvous with Sir James Ross’s search expedition, consisting of HMS Enterprise and Investigator. North Star, under the command of Master James Saunders, would carry provisions to help continue Captains Ross and Edward Bird’s Franklin search. Saunders was familiar with the Arctic and the lost ships: he had served on Terror for George Back’s 1836 Frozen Straits Expedition. Before the veteran warship and her forty crew members could depart, she had to be extensively modified to survive in one of the harshest maritime environments.

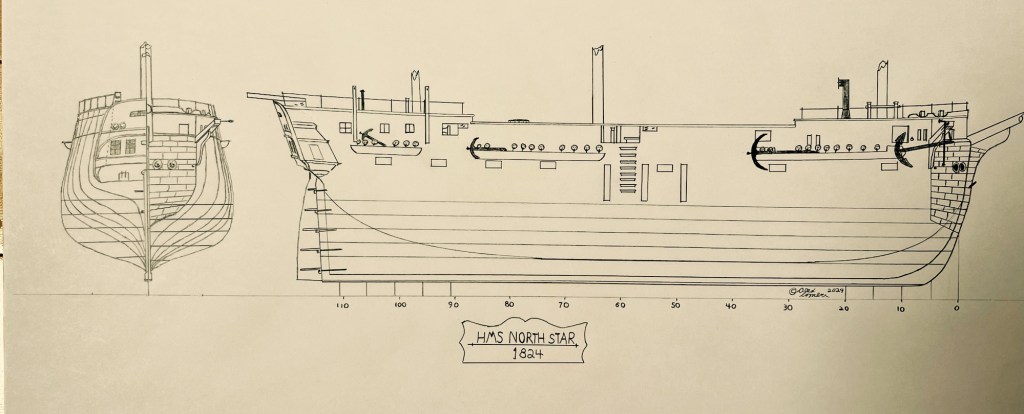

Master Shipwright Oliver Lang, who had been involved in the 1845 modifications to Erebus and Terror, supervised the work. More than a hundred shipwrights were tasked with the modifications at Sheerness dockyard from late February 1849. In April, that number surged to two hundred. They worked feverishly to get the ship ready for a mid-May sailing. Of all the ships that Lang was involved in refitting for Arctic service, North Star was special. What emerged from drydock wasn’t like the three other Atholls involved in the Franklin searches. It wasn’t last war’s corvette, a light survey vessel, a troopship, or some “Donkey Frigate.” Lang had created a monster! The design looked whacky, but it would prove to be the right kind of crazy for the challenges that awaited the Belcher Expedition in the Arctic.3

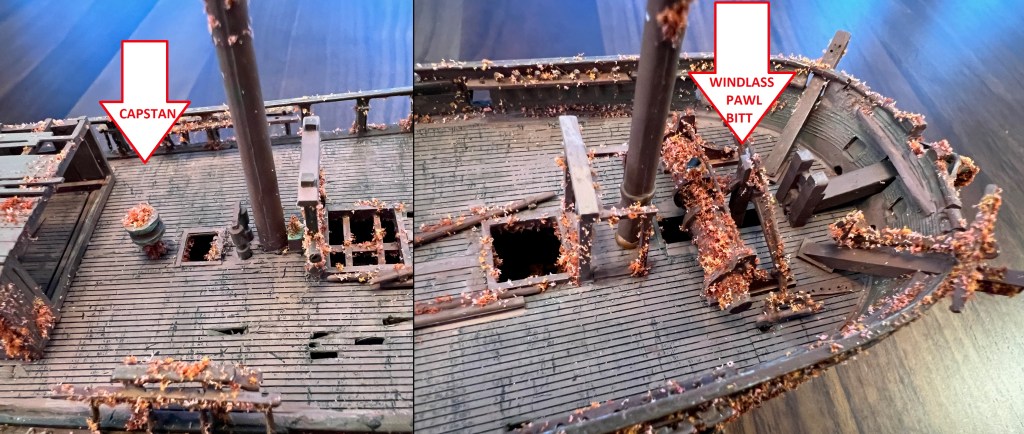

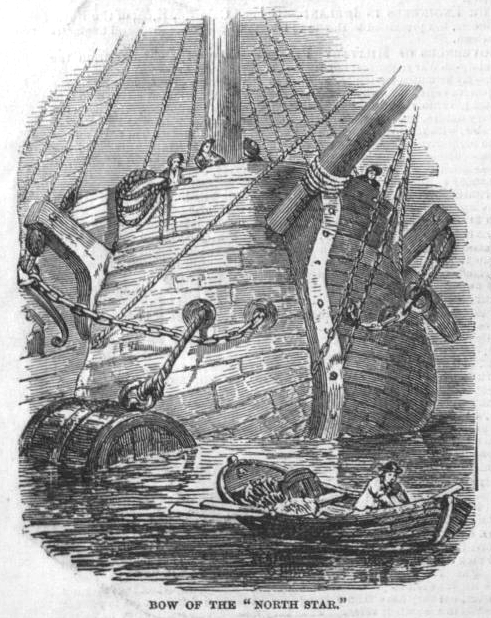

The headrails and decoration at the bows were removed and a prominent ice guard of iron sheathing was installed. This projected out on a shelf-like section. Two massive hawse holes pierced this ice guard on either bow, to pay out and haul in the thick anchor cables. Reinforced catsheads supported massive port and starboard bower anchors.

Stretching aft along the sides of the hull, the channels were filled-in to protect the shrouds against ice damage, and massive vertical riders were installed amidships near the entryway stairs. Along the gundeck, several gunports were deleted, while the remaining ones were simplified to small scuttles-an identifying feature of this vessel. Heavy davits were hung out over either quarter over the mizzen channels to hold the boats securely. The davits over the stern had to be especially strong as this was also a location to hang the comparatively fragile rudder off of when the ships were beset in ice.

The decorative stern and quarter galleries were simplified, with the lights (windows) appearing as narrow slits. Another pair of hawse holes appear to have been installed in the transom over the stern at the level of the quarterdeck, in a similar position to sister Rattlesnake’s fittings (an image of this appeared in the earlier post). These may have been intended to help position the vessel during anchoring or for shifting cargo to expedition vessels alongside. Flanking this rugged stern, the old quarter galleries were simplified. The three-masted ship rig was reduced to a barque by simplifying the yards of the mizzen mast.

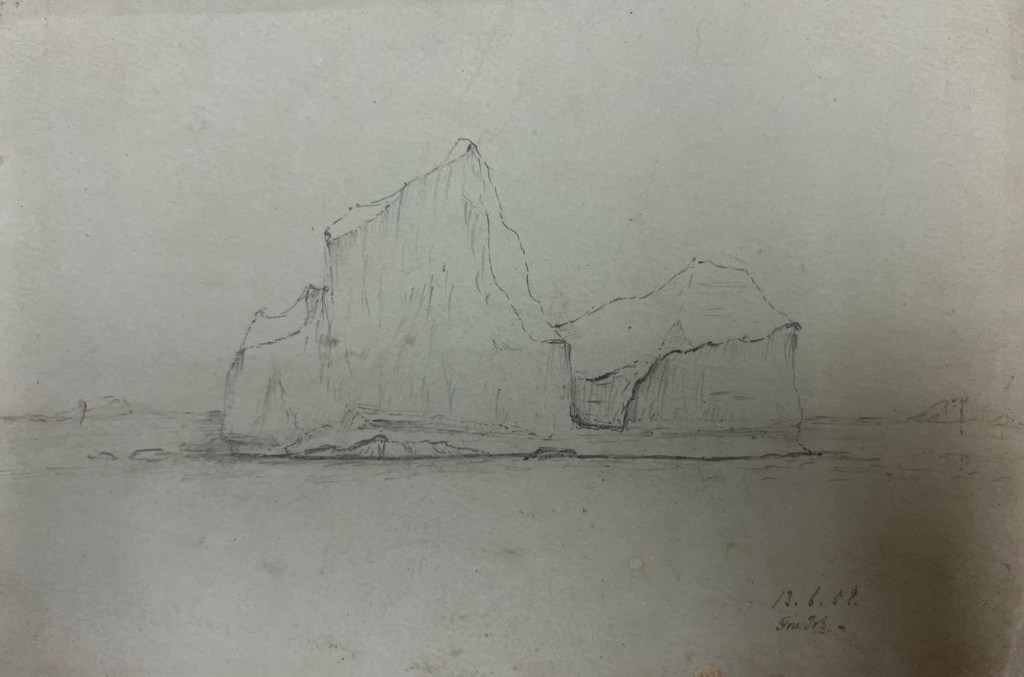

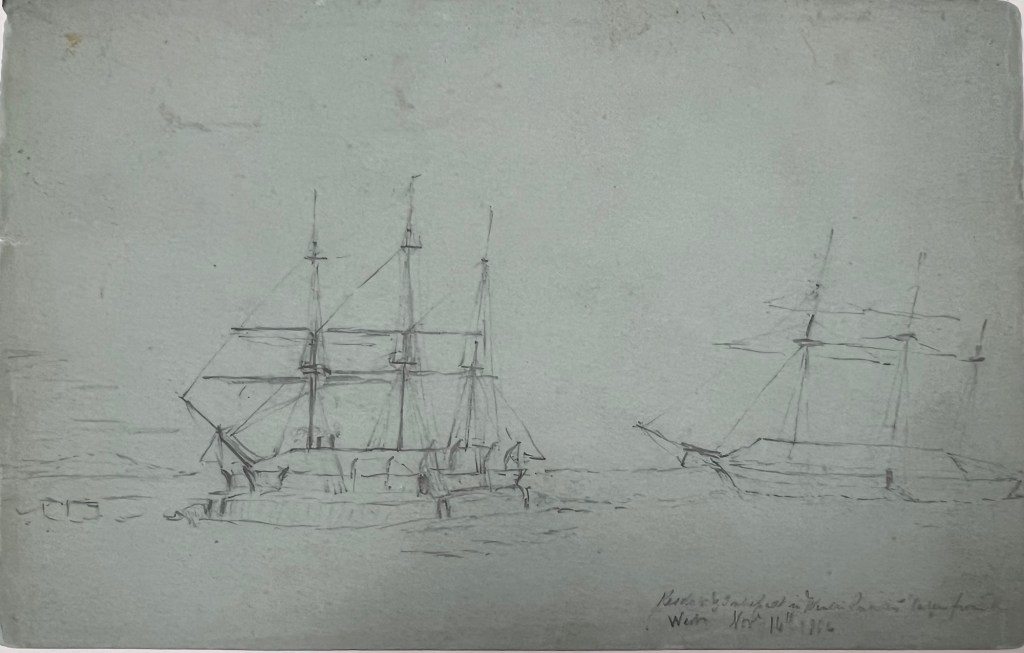

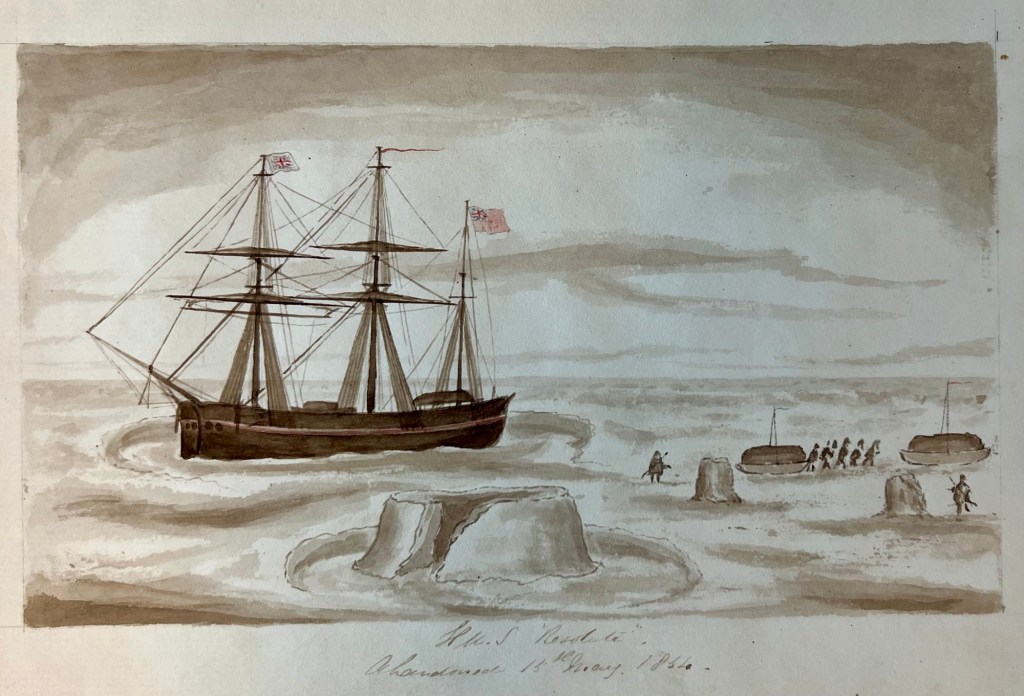

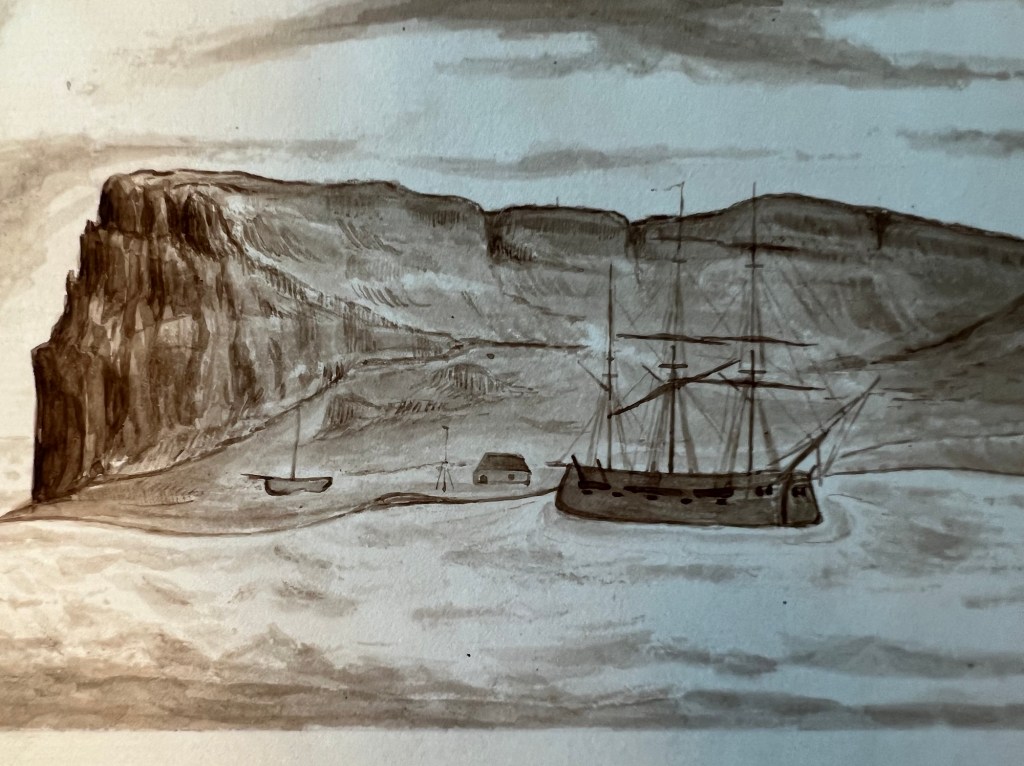

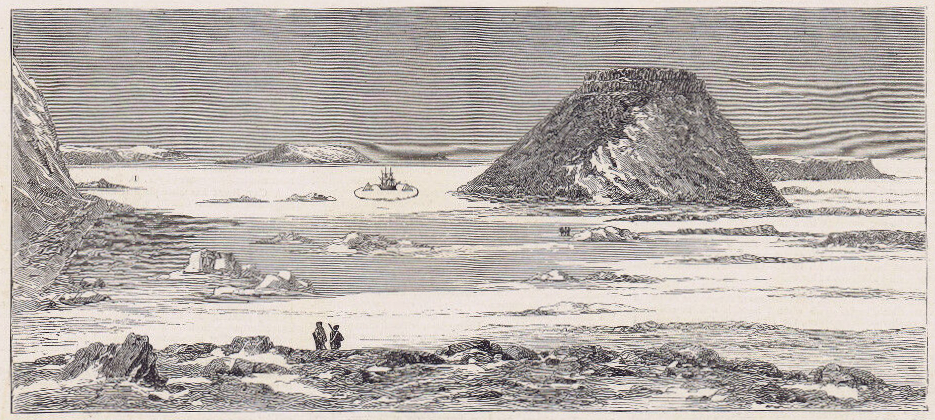

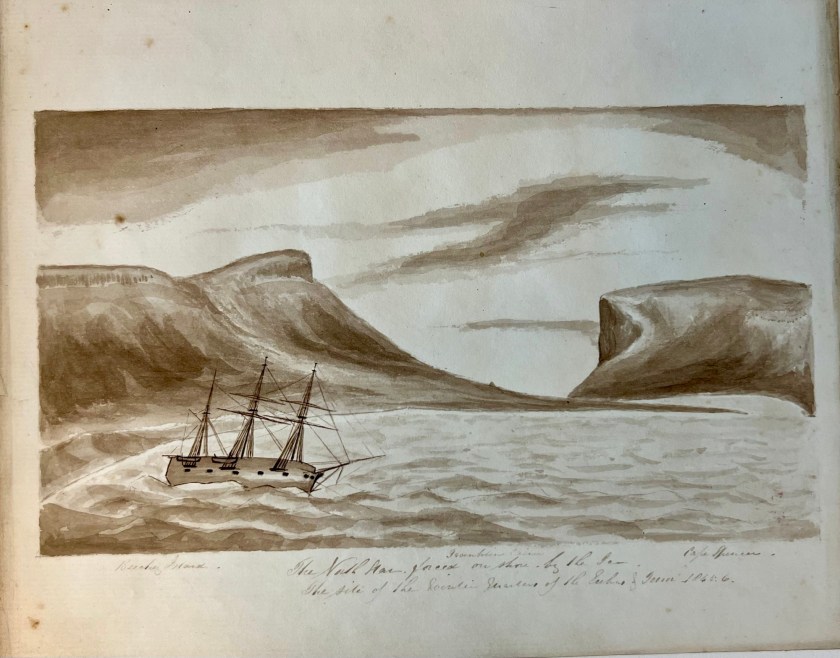

North Star was towed from Greenhithe by HM Steam Vessel Stromboli, departing 16 May 1849. As the season progressed, Saunders was not able to locate Ross, and instead dropped stores where they may have come in handy to either Franklin’s crews or expeditions searching for them. He departed the Canadian Arctic to re-cross Baffin Bay to Greenland. On the return journey, North Star endured treacherous ice conditions starting in July, and was nearly crushed several times. Eventually the crew sought shelter at Wolstenholme Fjord and the ship was beset in September. They overwintered further north than previous expeditions, on the coast of northwest Greenland near a table-topped mountain named Dundas Hill (Umanaq).

Four crew members perished during this time, and were buried nearby. When the ice cleared, Saunders turned west to return to the Canadian Arctic, to Baffin Bay and Wellington Channel, depositing more supplies at Navy Board Inlet. He learned that Ross had sailed for home from a chance encounter with William Penny (leading a privately-funded search expedition). North Star returned to England in the summer of 1850. Penny and Capt. Horatio Austin’s crews jointly discovered that Beechey Island had been the site of Franklin’s first overwintering – an event that would focus subsequent searches.

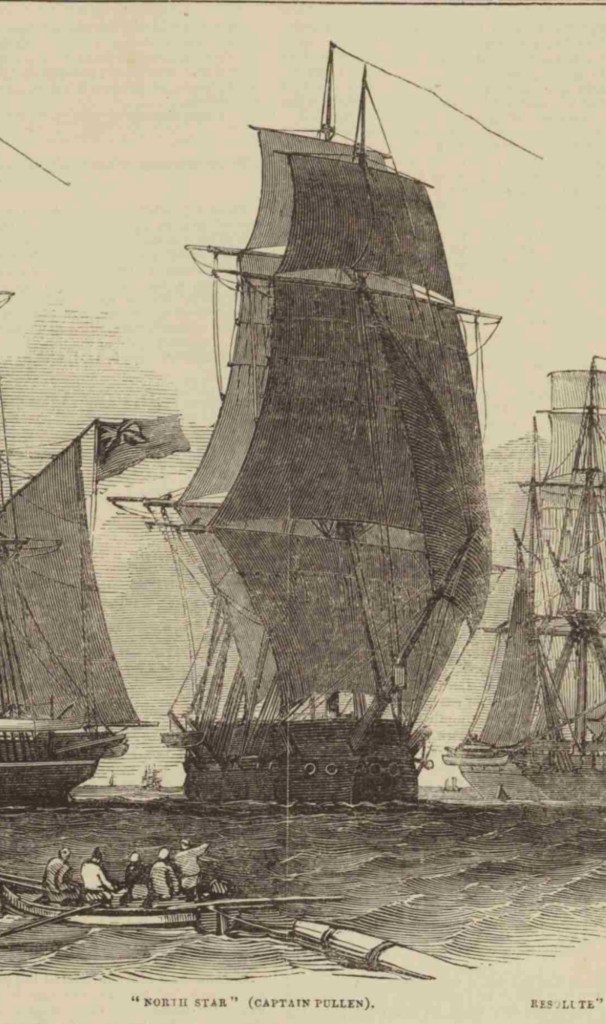

The Admiralty sent North Star back up again in early 1852, under the command of William J.S. Pullen. Pullen had distinguished himself in boat-led exploration missions while detached from the early western Arctic searches of HMS Plover and Herald. The new assignment was to travel with the large search squadron now being assembled by Sir Edward Belcher: HMS Assistance (Cmdr. George H. Richards) and HMS Resolute (Capt. Henry Kellett), and their steam tenders, Pioneer (Cmdr. Sherard Osborn) and Intrepid (Cmdr. Francis Leopold McClintock). North Star’s role was the unglamorous-yet-vital one of supply and provisioning.

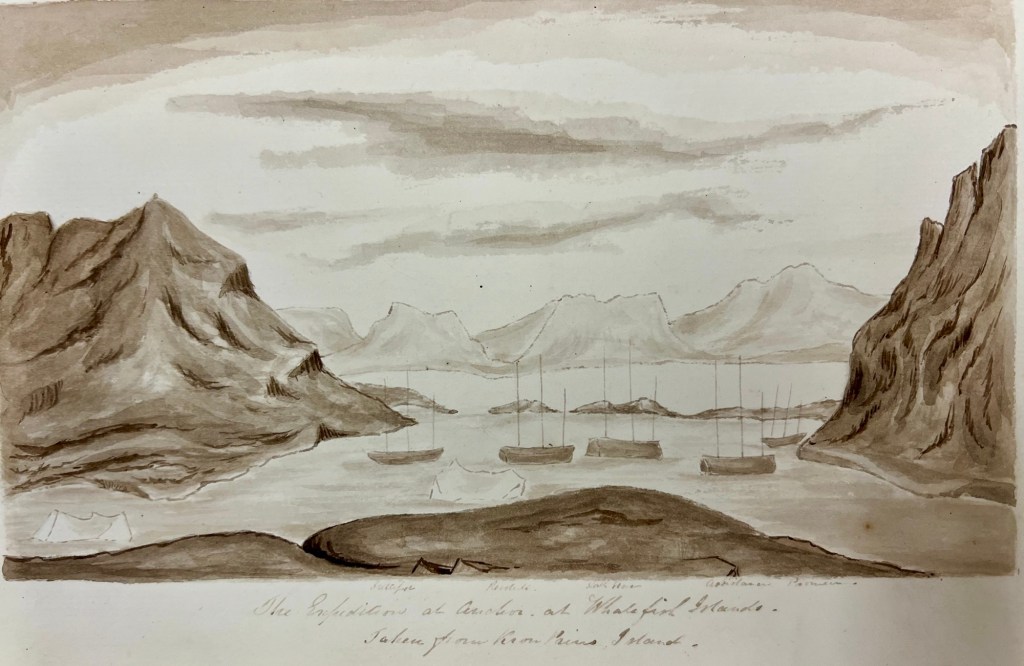

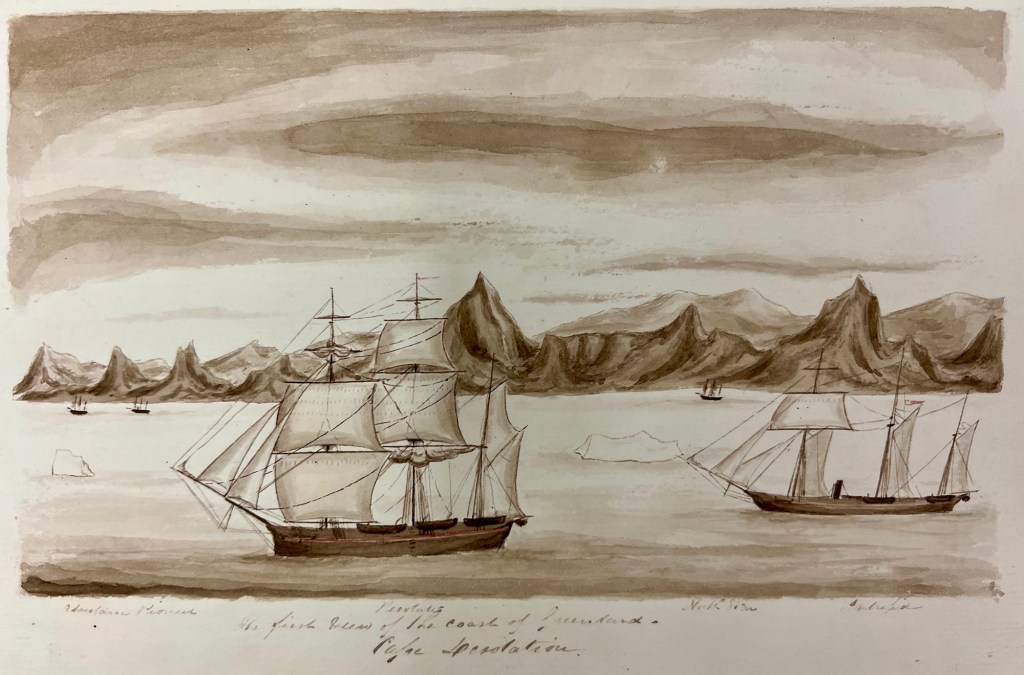

“The first view of Greenland, Cape Desolation 21 May 1852” the Belcher squadron is all depicted, with Kellett’s and McClintock’s commands, Resolute and Intrepid, in the foreground, passing some bergy bits. Credit: Mumford Fonds, Library and Archives Canada 86-18-3

The Belcher Expedition used the same successful quartet of vessels that had gone up under the command of Austin in 1850, but added the depot ship to the mix. This, it was hoped, would help the search ships explore further and stay on mission longer than previous attempts to locate the long-lost Expedition.

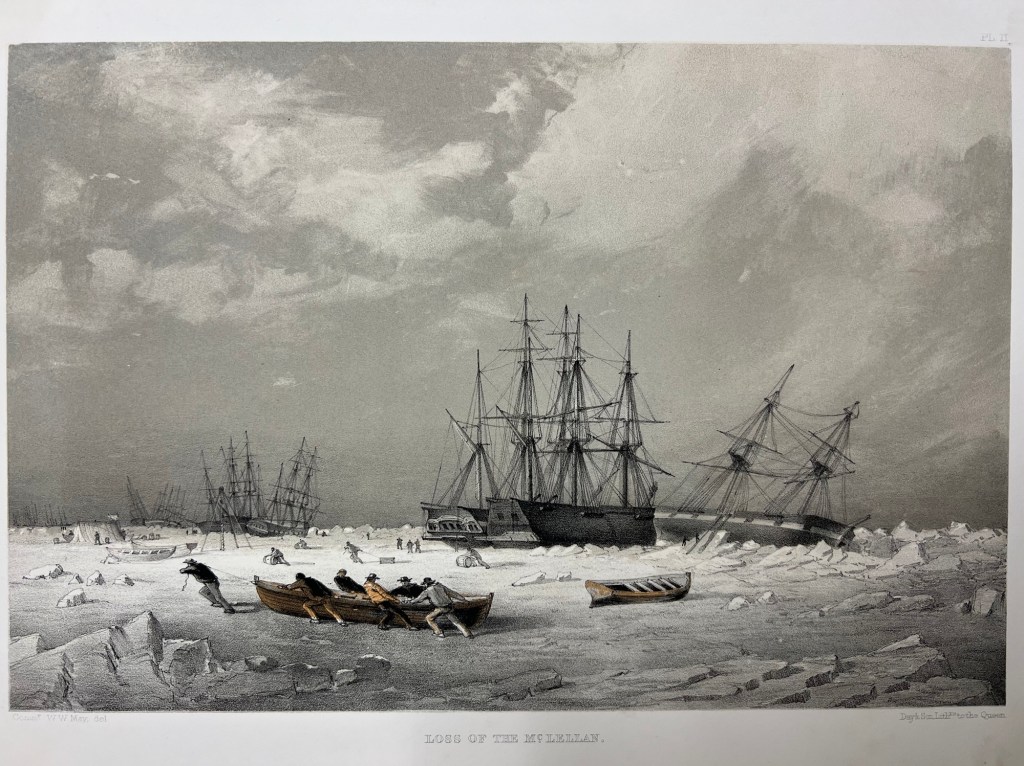

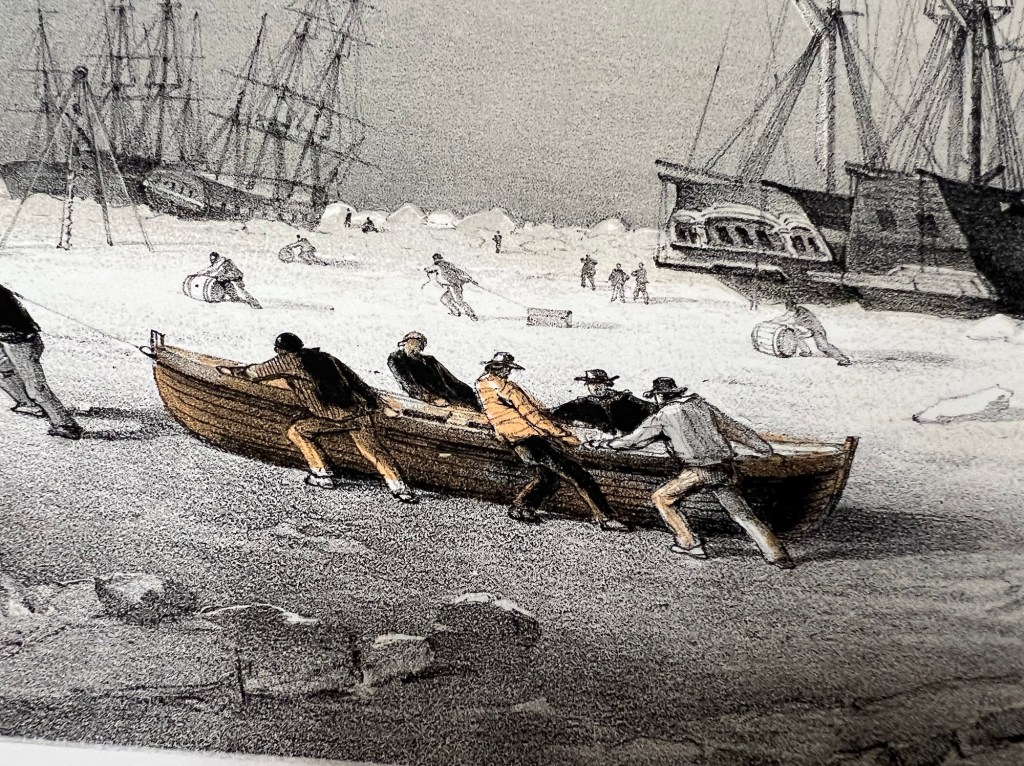

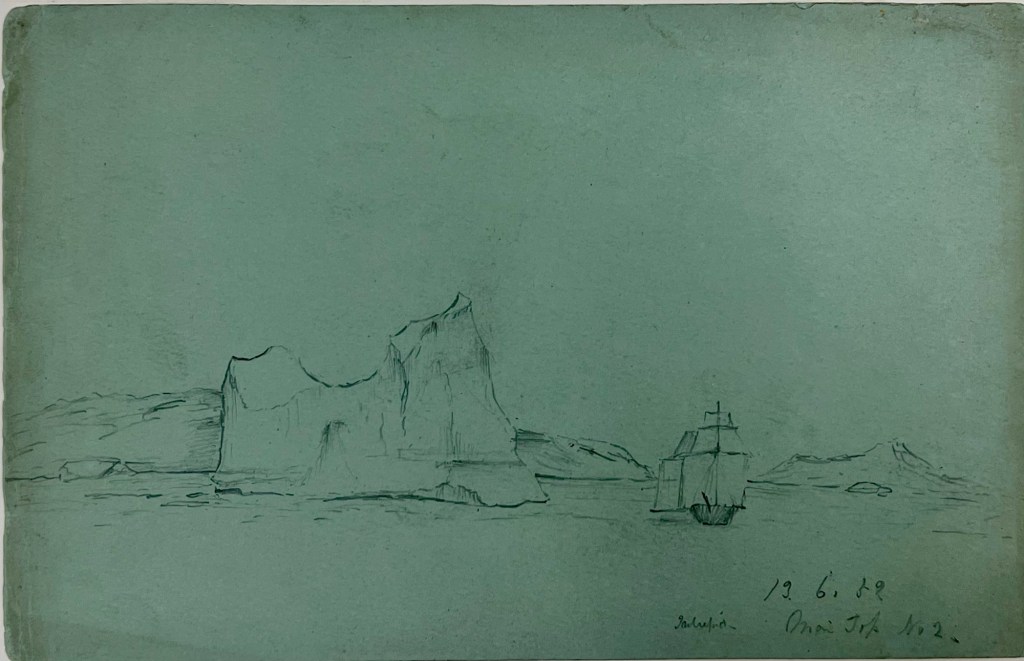

In early July 1852 the squadron was moving up Baffin Bay. They encountering some of the yearly whaling fleet while navigating along ice floes. North Star was damaged by the American barque McLellan. The threat of being caught between land floes and the floating pack ice was ever-present. A moment’s change in conditions could “nip” ships between these two frozen masses, without sufficient time to cut a protective “ice dock” into the land floe. Several whalers and North Star were nipped July 7th. The shuddering and wild pitching of hulls created a demonic clanging of ships’ bells. The unfortunate American whaler had also been forced against both North Star and the Alexander whaler (from Dundee). North Star‘s starboard cathead was mauled, and crew worked frantically to save the jibboom and bowsprit. As McLellan was further destroyed on the 8th, carpenters salvaged much of the hulk, and set North Star to rights.

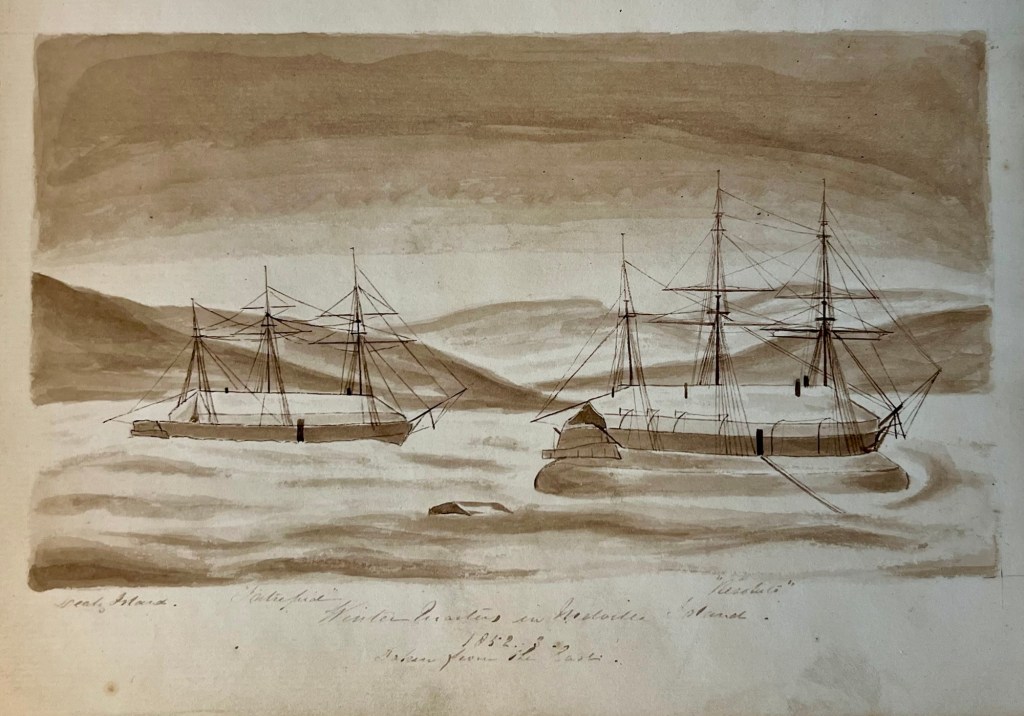

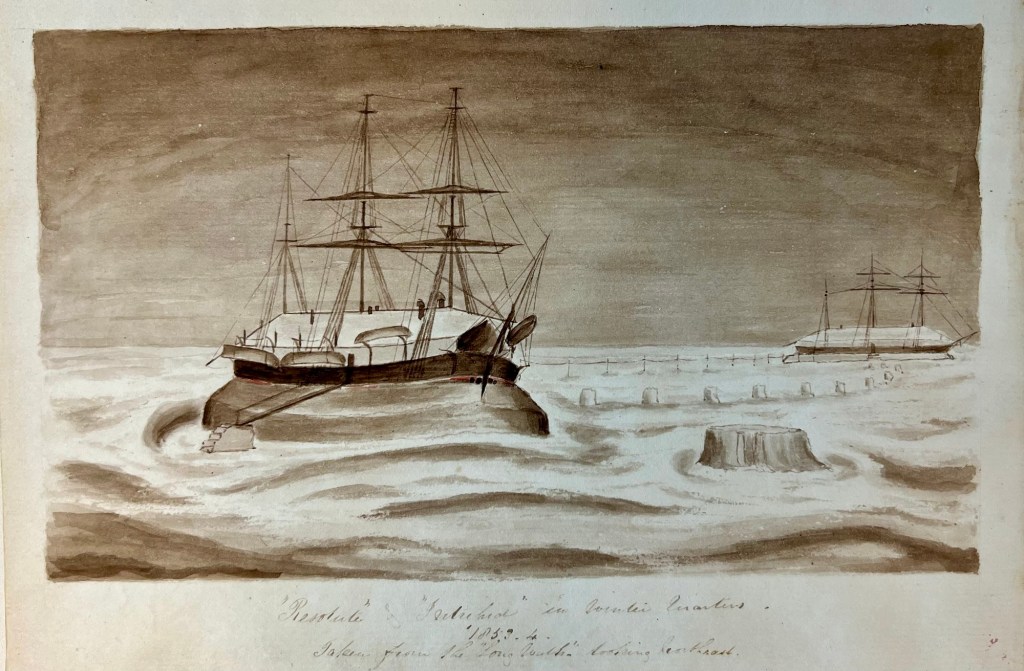

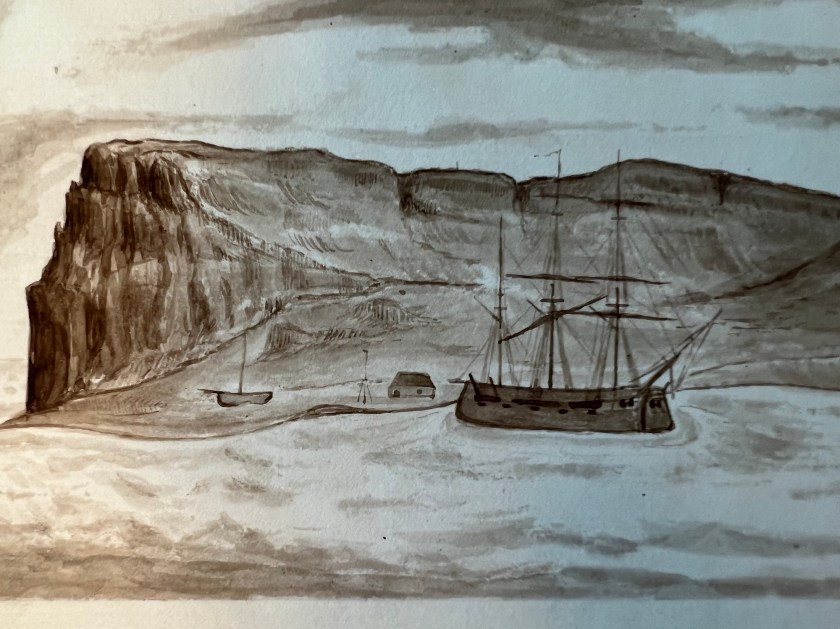

Days later, the ship was proceeding up Lancaster Sound along the southern shores of Devon Island. Even with her rugged alterations, North Star proved the finest sailer in the squadron.4 In August, at Beechey Island, the search ships topped up coal stocks from the depot ship’s supplies. Assistance and Resolute departed separately with their steam tenders to search different areas of the Arctic archipelago. They deposited caches of supplies and left records in prominent cairns as they went. North Star’s coal supplies were vital to extending the range of the whole effort: The combination of sail and towing by steam tender proved especially successful to advancing deep into uncharted passages and extricating Assistance and Resolute from perilous conditions. North Star remained at Beechey Island from 1852-1854, overwintering twice in Erebus and Terror Bay.

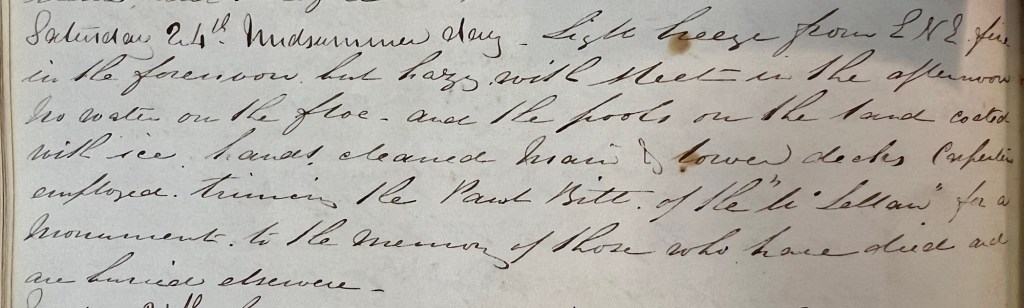

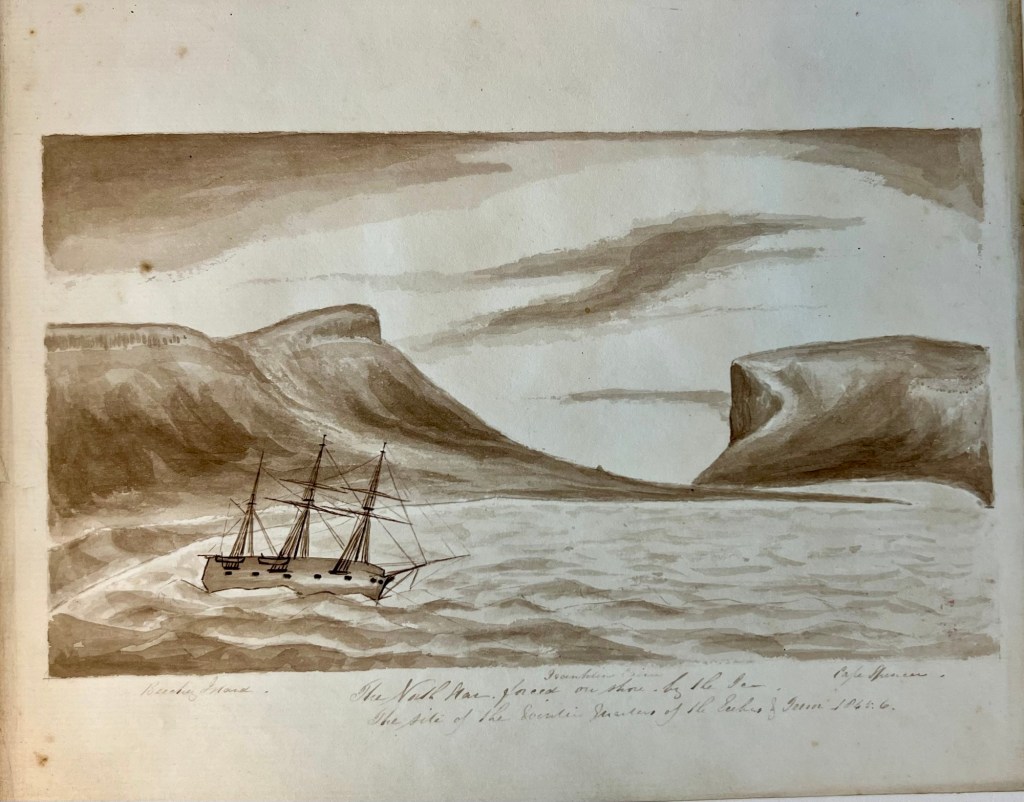

In September, as the Barrow Strait became a treacherous seascape of shifting ice, the Bay froze over. North Star was almost destroyed against the shore. The next June, she was again forced up. In between existential crises, Pullen kept his crew busy building up the shore establishment at Beechey with a new depot/storehouse, Northumberland House, built from components of the lost whaling ship. Crew moved Mary, a yacht left by Sir John Ross, to Beechey from nearby Cape Spencer to serve as a “rescue yourself” lifeboat, should anyone require it. In 1854 ships’ carpenters even built a cenotaph to commemorate their lost shipmates, again from timbers salvaged from McLellan.

The North Star and the Beechey establishment remained as the vital link in the logistical chain that sustained the Franklin search. Other vessels, under the command of Captain E.A. Inglefield, journeyed from England to resupply North Star at Beechey in the high summers of 1853-54. In early 1854, with crews weakening from the effects of scurvy and other ailments, and with no immediate prospect of escape for the ice-imprisoned search ships, Sir Edward Belcher took the difficult decision to order his captains to abandon their ships. Crews would sledge back to Beechey, along a route they knew, that they themselves had stocked with supply depots. Pullen and his forty crew assisted in bringing them in, provided medical assistance to the weakened, closed up Northumberland House in good order, and cut their own canal out of Erebus and Terror Bay to start for home at the end of August. Five crews adding up to about 230 sailors had abandoned their frozen ships and were in sledging parties marching a long trail through difficult terrain. But, unlike the 129 dead men they had been sent to find, these sailors knew they were trekking back to salvation – a beacon in the High Arctic – their familiar North Star.5

- This account draws from the article “Icy Imprisonment: the 1848 Voyage of the HMS North Star” at https://beyondthebackyard.com/2014/09/03/icy-imprisonment-the-1849-voyage-of-the-hms-north-star/ and from Richard J. Cyriax (1964) “The Voyage of H.M.S. North Star, 1849-50” The Mariner’s Mirror, 50:4, 302-318. (which was provided to us with thanks from Randall Osczevski). I would also like to thank Fabiënne Tetteroo for providing higher-resolution images of the first and third ILN illustrations used above, and Elizabeth Matthews of HMS Resolute, for the same help with G.F. McDougall’s “The Loss of the McClellan – American Whaler.” ↩︎

- Please see our earlier post on the Atholl Class sister ships that were involved in the British search efforts for the missing Sir John Franklin Expedition, for a description of the original design of the class of fourteen ships and a brief account of the Franklin search-related careers of HMS Herald, Rattlesnake, and Talbot. The group contributed a lot to the Franklin search efforts! ↩︎

- To see how far the original Atholl class corvette design had evolved, see for example, the 1844 plans of sistership HMS Crocodile (1825), modified for rugged service as a surveying ship, also with a fortified bow guard, and a built-up weatherdeck: National Maritime Museum ZAZ5498. This was an important source for our reconstruction. There would also have been an extensive doubling, fortification, and interior strengthening of the hull of North Star. Our plan is not considered a final plan, but is a simplified representation, and it is the only of its kind. ↩︎

- Observers on HMS Resolute, George McDougall and William Mumford, both commented in August 1852 entries on North Star’s turn of speed while detached to arrive at the rendezvous of Beechey to check for Assistance and Pioneer (who had become separated but were themselves were still miles away). McDougall’s 1857 published account is currently available online at babel.hathitrust.org. Mumford’s invaluable diary exists as the main part of his archival fonds at Library and Archives Canada. ↩︎

- HMS Investigator’s 61-man crew, frozen in at Mercy Bay, was fortuitously located by a party from HMS Resolute under Lt. Bedford Pim on 6 April 1853. Robert McClure abandoned Investigator, and moved his ailing crew over to Resolute and her steam tender Intrepid (which eventually allowed him to claim his crew had been first to transit-not sailing- the Northwest Passage). I have counted the crew in with the 180 other men of the search ships. HMS North Star’s crew was about forty strong, if she had the same numbers born as for the 1850-51 voyages, making the Expedition total to about 281 men, 13 of whom, tragically, died in the course of their service and are commemorated by name on the remote but important Beechey Island Cenotaph. The French officer Lt. Émile-Frédéric de Bray, in his published account, lists the total number of personnel at 263 (Quoted in Barr and Stein’s “Frederick J. Krabbé, last man to see HMS Investigator afloat,

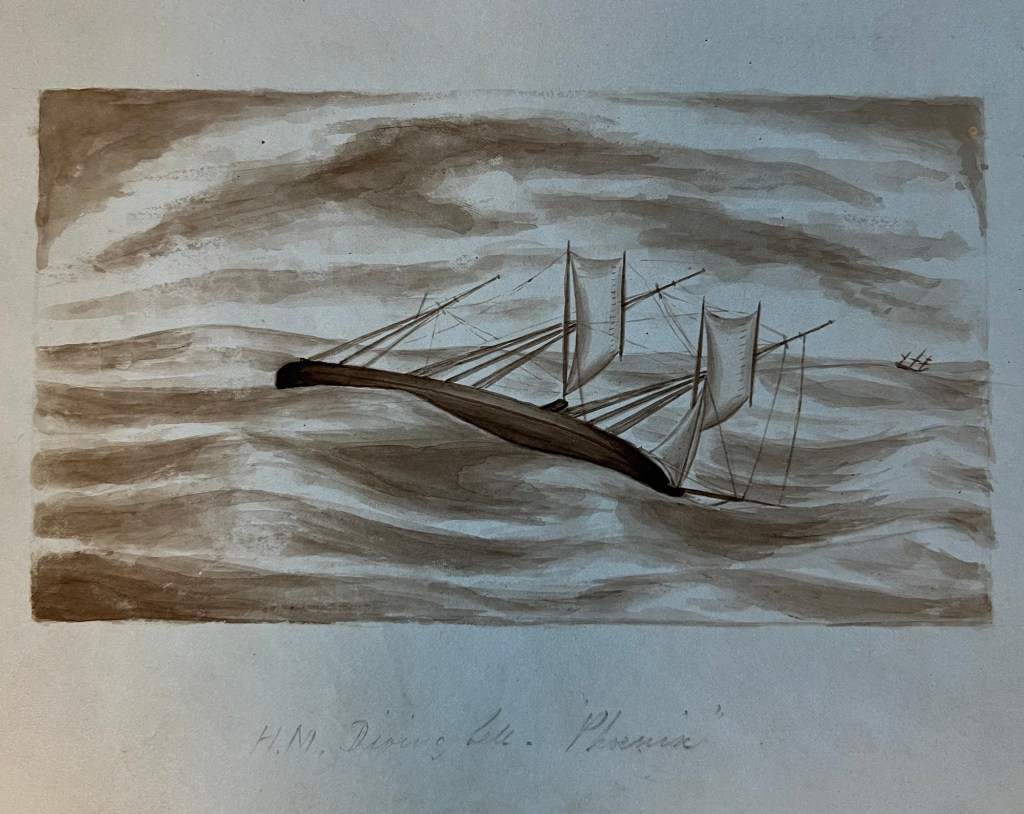

May 1854″ Journal of the Hakluyt Society 2017/01 P28). As North Star was leaving Beechey on 26 August 1854, HMS Phoenix and Talbot (North Star’s sister ship) arrived on their resupply mission, and so helped disperse the Belcher crews to transport them home to England in three vessels. ↩︎