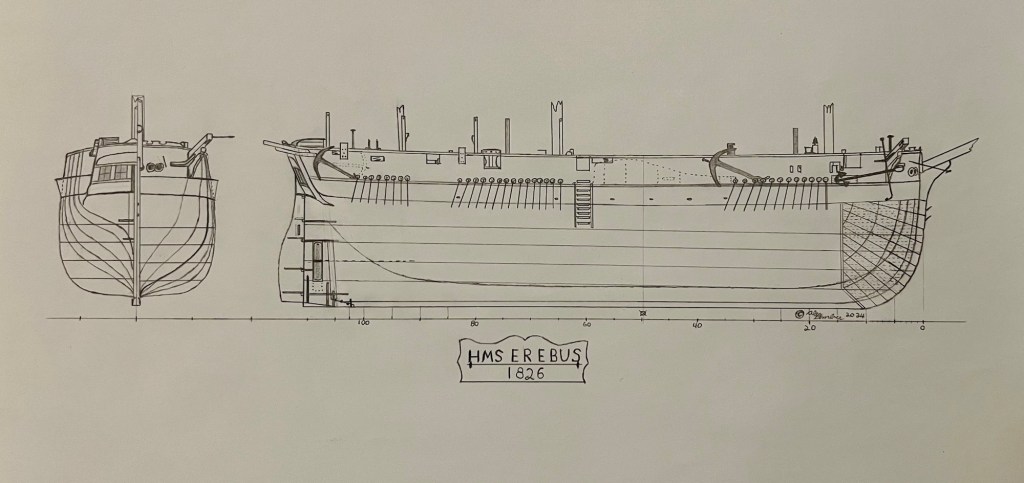

Ten years ago, the sea gifted us back a legendary ship, lost for almost seventeen decades: HMS Erebus. As visitors to our site know, there is a lot of Terror talk on this blog! HMS Terror, was the “other ship” on Sir John Franklin’s ill-fated 1845 expedition to discover a Northwest Passage. We had been neglecting Erebus, and are now trying to make amends! Interpreting a variety of archival sources, we decided to attempt a simplified set of plans of this incredible ship to mark the important anniversary of Erebus being back in our World:

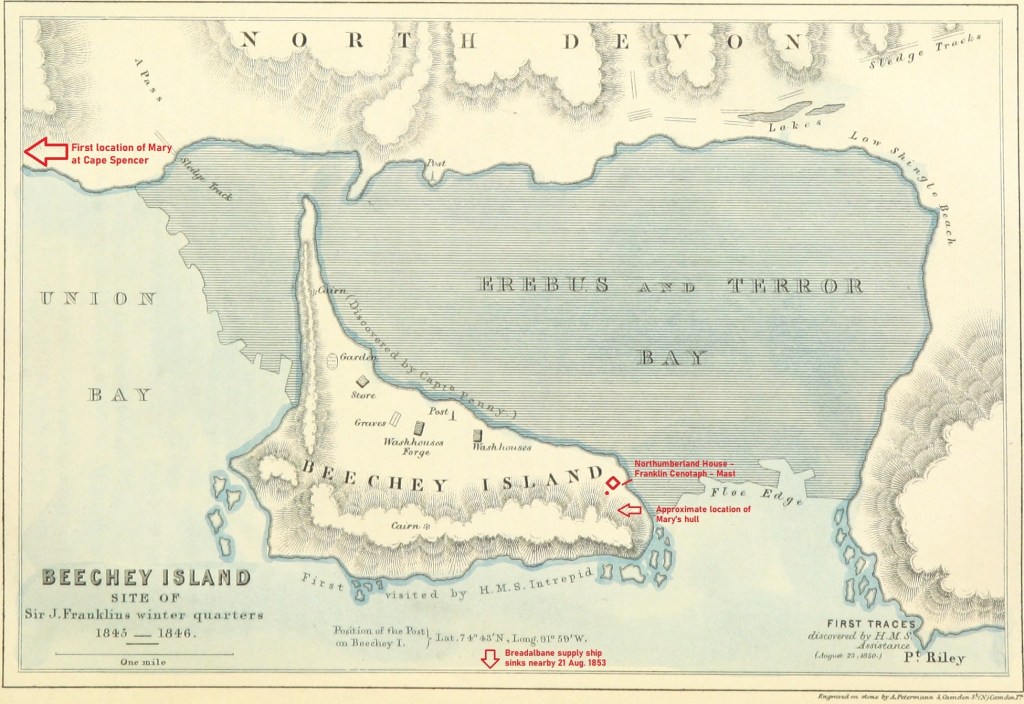

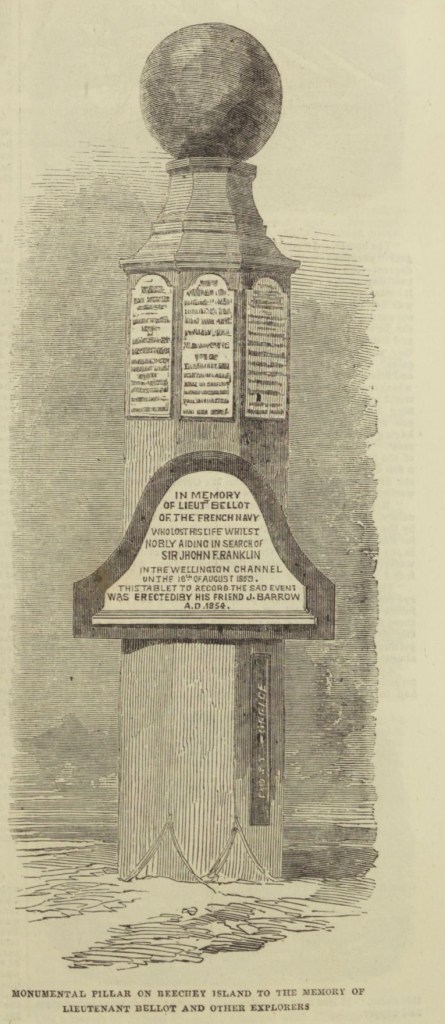

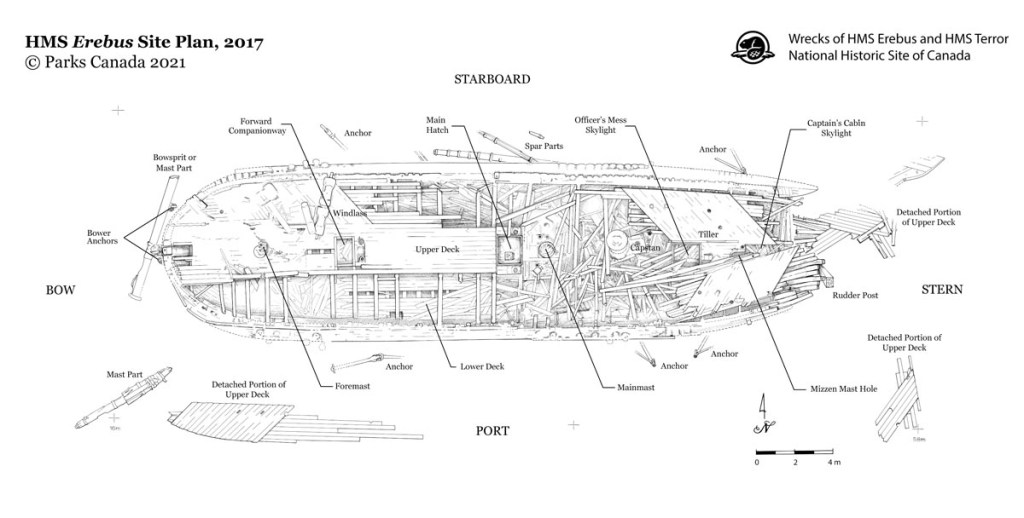

On 7 September 2014, Parks Canada, a key member of the Victoria Strait Expedition – a consortium of government and private partners – definitively located one of Sir John Franklin’s lost ships. A promising sonar target had been identified in Wilmot and Crampton Bay, Nunavut, on 2 September, after archaeological finds on a nearby island had redirected the search. The Parks Canada Underwater Archaeology Team (UAT) deployed a Remotely Operated Vehicle aroung the well-preserved remains of a shipwreck, located in only 11 meters / 36 feet of water. By the afternoon of the 7th, it was clear to the team that the vessel was one of Franklin’s elusive ships. The UAT informed Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s Office. Further investigation by the UAT dive team allowed them to definitively identify the ship on 1 October as HMS Erebus.1 The discovery tied into a rich tradition of Inuit oral history, which had suggested, down through the 166-years of searching, that one of the lost ships had come to grief on the western coast of the Adelaide Peninsula.

The moment had finally come for Erebus, that personification of darkness, of gloom, of the unseen World, to come back into the light; it was time for Sir John Franklin’s lost flagship to be restored to the public consciousness. The discovery was an immediate sensation, and ten years on, the yearly program of archaeology – of surveying, imaging, artifact recovery and conservation – continues to be followed with great enthusiasm.

On the day the find was announced, 9 September 2014, as media reports appeared on my device, I was staring at a damaged ship’s wheel and a bell recovered from another famous shipwreck – and one of Canada’s worst maritime disasters – RMS Empress of Ireland. These were on display in the exhibit Empress of Ireland: Canada’s Titanic at the Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau. I bought a commemorative bell, walked across the Alexandra Bridge to stand under the statue of explorer Samuel de Champlain – wielding his famous astrolabe over Nepean Point (now Kìwekì Point) – which looks out over the Canadian capital – and rang the bell to celebrate the discovery! It doesn’t have to make sense, it just felt right.

HMS Erebus was a Hecla class bomb vessel completed in 1826, long after the conflict the “bombs” were designed for had terminated. This small warship was about 370 tons burthen, about 105′ / 32m on the gundeck (later considered the lower deck), with a beam (width) of about 28′ / 8.5m. The class was originally armed with two massive mortars – 10” and 13” varieties – housed in rotating carriages in firing beds overtop of reinforced cribbing, that also stored their massive shells. The mortars were located along the centerline of the deck between the fore and main masts. A few cannon installed along the gundeck rounded out the armament, and enabled the ships to defend themselves and perform auxiliary service as a convoy escorts – a useful secondary role during the Napoleonic Wars, when enemy warships and privateers were a constant worry to keeping merchant sea lanes open. The first Heclas were completed at the very twilight of the Wars, and took no active role. Hecla and Fury did participate in the August 1816 Bombardment of Algiers, firing hundreds of shells into the fortified city. In 1819, to lead William Edward Parry’s first exploration mission north, Hecla was converted to the radically different role of polar discovery vessel. For Parry’s next two exploration missions (1821-1825), Fury accompanied Hecla. This revived a tradition of the crews of two reinforced bombs working together on polar missions.2

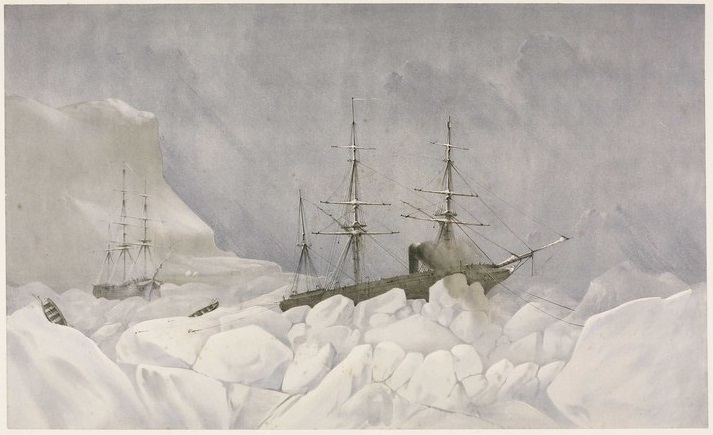

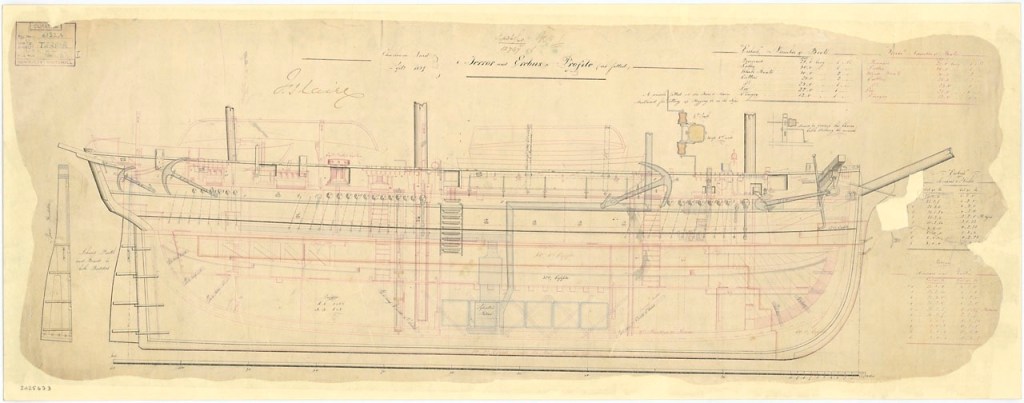

Erebus, completed the next year at the Royal Navy’s Pembroke, Wales, dockyard, remained in ordinary (out of commission), awaiting a day when the Royal Navy would have need of this compact, incredibly specialized warship. Her first missions saw her employed in the Mediterranean making ports-of-call visits and showing the flag, the typical peacetime routines of the “wooden walls” – the ships of Britain’s massive naval fleet.3 In 1839, Erebus’s moment came to be modified, but it was for an entirely new theatre of polar operations: The exploration of Antarctica. Erebus was selected to be the lead ship in James Clark Ross’s expedition south. The older and smaller Terror (commanded by Francis Crozier) accompanied her. The waist was decked over in a continuous weather deck, as the mortars were unshipped and the massive beds were removed. The ship’s basic skeleton – keel, frames and knees – was reinforced, hull planking was doubled, and this new weather deck was overlayed with diagonal planking. An enormous ice channel or chock now extended from bows to the stern, girdling the hull more completely than earlier exploration ships. The elaborate seven-light (windowed) stern with overhanging quarter galleries was reduced to five lights across the transom, in a simplified design. The entire underbody of the ship was clad in a shining layer of copper plating, but certain areas, such as the bows and waterline, were reinforced with special thickened copper. The vessel that emerged from refit looked less like a pint-sized frigate from the Wars, and more like a bulked-up whaling ship.4

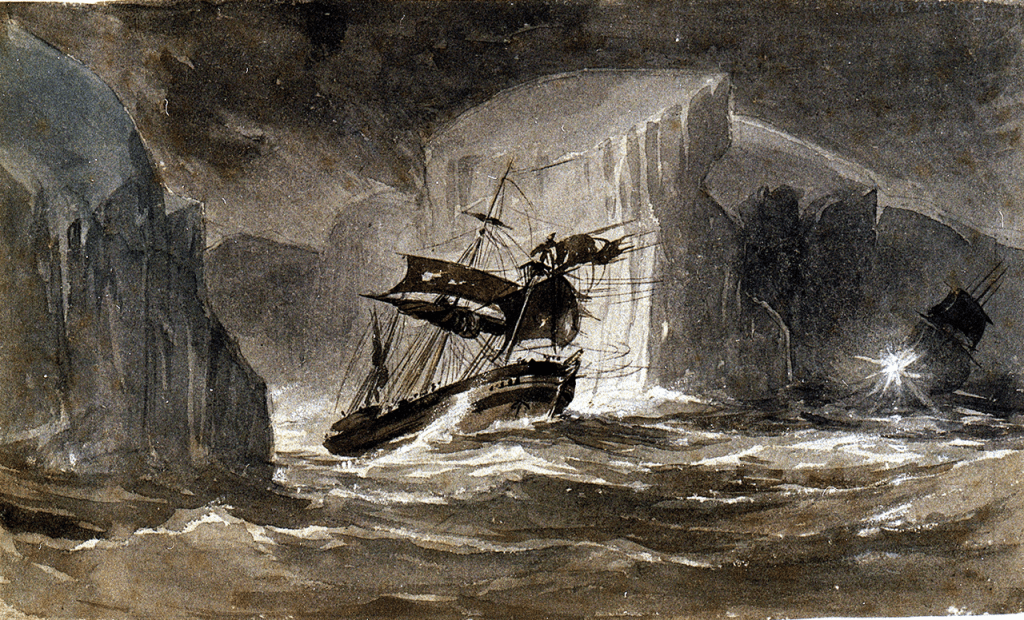

The crews of both vessels succeeded brilliantly on their four-year surveying odyssey, charting vast coastal expanses and ice shelves of the most southern continent, and making important scientific discoveries in biology, zoology, and magnetism. Operating in totally uncharted waters was perilous work, with Erebus and Terror both being damaged in an almost fantastical collision while dodging icebergs. Despite the hazardous environment, casualties on the voyage were incredibly light.

After repairs and a brief lay-up, the “Discovery Duo” was selected for the next major polar effort: Sir John Franklin’s 1845 bid to chart the last section of the Northwest Passage along the top of the North American landmass. Another major rebuild followed. A reinforced iceguard of massive iron plates was fitted to the stem and forefoot under the bows. A radical alteration to the stern timbers allowed each ship to operate a screw propeller, powered by a converted railway steam locomotive (please see our subsequent post about HMS Terror’s screw propeller to explore this interesting technological update). When not in use, the screw could be uncoupled from the drive shaft, and raised into a protective cavity that hung inside the stern. These small engines, with a very limited supply of coal for fuel, were intended to help the ships navigate in the challenging Arctic environment without being fully dependent on the wind’s vagaries.

Franklin, installed on Erebus, would lead the expedition. James Fitzjames commanded the flagship, while Crozier, Second-in-Command of the effort, remained in his familiar Terror. As most visitors to this site likely are aware, this was to be a one-way trip for ships and crew, that ended in disaster, shipwrecks, boatwrecks, and a trail of abandoned items, burials and bones. Of the lost 129 expedition members, 67 had served on Erebus. The hulk somehow wound up wrecked in Wilmot and Crampton Bay, south of King William Island. Just like the wrecking of HMS Terror nearby, the exact details of the Erebus sinking have yet to be established.

What were the main differences between Terror (Vesuvius class) and Erebus (Hecla class)? These were not sisterships, though they appeared so similar most observers may have thought they were. Both ships were tubby, and very similar to merchant designs, with their bluff bows and broad hulls. The differences were summarized by Dr. Matthew Betts, an expert in HMS Terror’s design and history, in his blog post “What’s the Difference – Franklin’s ships compared“. Henry Peake’s original 1813 design for the Hecla class emerged iteratively out of his earlier design for the Vesuvius class. The enlargement of 50 tons displacement and deepening of the hull are less visible than the overall impression the original plans provide: Terror’s lines harkened back to a time of more elaborate decoration and sweeping sheer (sheer being the lengthwise curvature up by the bows and stern, down at the waist); Erebus was more upright, with stem and stern posts that dropped from the ship’s built-up rails almost straight down, and a flatter sheer. The very bottom of the ship, out from the massive keel, was broader in Erebus, while Terror had a noticeably more “V” shaped lower hull.5

During the 1845 refit, Terror’s bowsprit was seated much further aft, so that this heavy mast angled out forwards at the level of the rails. Erebus’s bowsprit remained in its traditional location, piercing the bow lower down, between the anchor hawse holes, and just above the visible ledge of the ice channel. As detailed in the “Design Dossier” link below, what is revealed from a close interpretation of plans and depictions of these vessels through their lengthy service is that Erebus, and the Heclas, had upper counters beneath their stern windows, whereas Terror and her two Vesuvius class sisters did not. Erebus also had six large scuppers a side that discharged via pipes halfway down the ice channel. These drained the weatherdeck. Terror had four large scuppers that discharged higher up, level with the deck and above the channel. Thus, by the time of their departure from Greenhithe on 19 May 1845, the ships featured distinctive elements to sort one out from the other at the bows, amidships, and aft.

To conclude, when it comes to the design of these two incredibly unique vessels, we are still very much on a voyage of discovery! It has been a decade since the heady days of the Victoria Straits Expedition’s location of Franklin’s lost flagship, HMS Erebus. Much has been discovered, and much remains to be found at both Erebus and Terror sites. Along with artifacts that allow us to explore the human tragedy – the loss of two shiploads of exceptional individuals – our knowledge about the exact design and advanced technology of both ships will continue to expand over the next decades. Parks Canada’s Underwater Archaeology Team is at the Franklin ships at this exact moment! What will they find this year?

“Westward from the Davis Strait, tis’ there twas’ said to lie; the sea route to the Orient, for which so many died. Seeking gold and glory, leaving weathered broken bones, and a long-forgotten lonely cairn of stones” (S. Rogers Northwest Passage – 1981)

CLICK HERE to read the “Design Dossier” for HMS Erebus, and Acknowledgments

The Design Dossier: To create my reconstruction and simplified plans, I had to interpret a variety of sometimes contradictory sources. This project followed on from the reconstruction of HMS North Star, Franklin search ship, and HMS Ontario historic shipwreck. This may only interest a few readers, so I will summarize this research. It adds up to a unique perspective on HMS Erebus. My starting point was the excellent archival collection of plans held at the National Maritime Museum (NMM), Greenwich. My simplified reconstruction omits some frame lines along the midships section for clarity, and because I drew the plans at a small but consistent scale of 1:125. A particularly fine set of technical drawings that show the body plans or hull lines exist at the NMM for Erebus sisters Meteor (1823) and Fury. These made it possible for me to reconstruct both the overall hull lines, and also the bow and stern elevations and body plans for Erebus. Without close adherence to these plans it would be virtually impossible to reconstruct these ships, absent more information from the wreck archaeology. Another guide in this reconstruction was the artistic works that Lt. Graham Gore [Scott Polar Research Institute item 35195957] and Capt. Owen Stanley [National Library of Australia collection item 2484731] created in 1845, as the squadron moved north. I am privileging their first-hand observations over certain other technical evidence. Gore, as First Lieutenant, would have had direct involvement with readying the vessels for sea in 1845, whereas Stanley had sailed in Terror during the 1836 Frozen Strait Expedition, and temporarily accompanied the squadron northwards while commanding HMS Blazer, a steamship towing Erebus. Gore sent his artistic depictions back for Lady Jane Franklin while the expedition members posted their final letters from Disko Bay, Greenland (Qeqertarsuup tunua).

- Erebus had a large -almost hemispherical- iron iceguard fitted to the bows. Parks Canada’s archaeology has documented iron plating extending from the stem all the way back to be level with the foremast. Their commissioned wrecksite diorama (built by professional model builder Fred Werthman) also demonstrates this expanse of plating. This appears to be larger than any polar-modified ship from before the Expedition and any of the search vessels that followed in the wake of the lost ships. Correspondence with Parks Canada’s Underwater Archaeology Team and Dr. Matthew Betts have substantiated this feature.

- A distinctive difference in the sterns of the ships is that Erebus always had an upper counter, whereas Terror never had one. An upper counter (see below HMS Victory model) is a space traditionally found under the lowest level of lights (windows) on the stern of a vessel, which also often has the nameplate or lettering identifying the ship. Developing to its classical appearance in the early 18th century, the design of the upper counter was mostly aesthetic, and made a visual transition to the more concave space of the lower counter (where the ship’s rudder usually enters the stern, and stern chase ports, if they exist, are located):

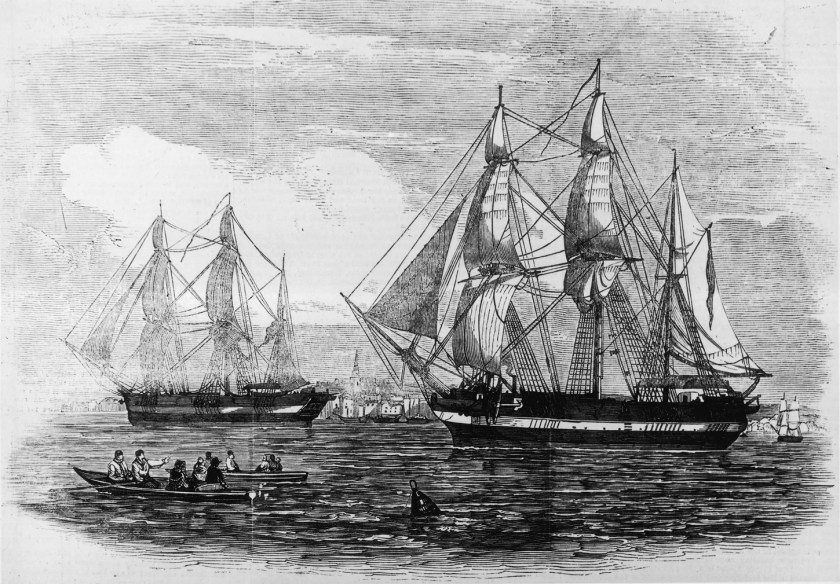

This small feature can be readily seen under the stern windows of Parry’s ships in the illustration of Hecla and Fury at top. Terror and her two Vesuvius class sisters (RMG ZAZ5615), by contrast, were more constricted aft and had less deck height in the great cabin, so no upper counter existed under the lights, even when the ship had full, frigate-like stern and quarter galleries. Terror lacked the upper counter in 1813, in 1836, and again in 1845, according to the NMM collections of plans, and a variety of depictions. The upper counter is documented for Erebus on Meteor and Fury‘s 1823 plans and her own 1839 plans as rebuilt for the James Clark Ross Antarctica mission.

This small feature can be readily seen under the stern windows of Parry’s ships in the illustration of Hecla and Fury at top. Terror and her two Vesuvius class sisters (RMG ZAZ5615), by contrast, were more constricted aft and had less deck height in the great cabin, so no upper counter existed under the lights, even when the ship had full, frigate-like stern and quarter galleries. Terror lacked the upper counter in 1813, in 1836, and again in 1845, according to the NMM collections of plans, and a variety of depictions. The upper counter is documented for Erebus on Meteor and Fury‘s 1823 plans and her own 1839 plans as rebuilt for the James Clark Ross Antarctica mission. - This era saw a lot of experimentation in naval architecture around the stern, to establish the most optimal means of fitting a screw propeller into an existing wooden warship. Oliver Lang (the shipwright for the 1845 modifications to both ships) was at the very heart of this innovative furor, and was involved in the design of the stern of revolutionary new types of steam sloops, frigates, and line-of-battle ships, all modified or designed from the ground up to fit the new models of screw propellers. I believe, when he came to modify these two veteran exploration ships with new propulsion, he omitted the traditional lower counter design from under the transom/stern galleries of both ships, rounding the tuck up, or carrying and uniting the hull planking upwards to meet the transom timbers. His 1845 technical drawing for the stern of both ships (RMG ZAZ5683) is an approximation, even when overlaid to produce the June 1845 “green ink” updates on the 1836 Terror plan (RMG ZAZ5672). The plan had to work for both ships, which had some significant differences in dimensions and stern post orientation. This plan’s inaccuracy can easily be observed when it was traced over to the 1836 Terror plan: The 1845 updates create lines at the level of the ship’s upper rail that have no sheer and terminate hanging in space! Those lines are a simple tracing of the left side sectional stern plan from the 1845 technical drawing, not the right side exterior elevation. This means they are a sectional view imposed inaccurately over Terror’s 1836 lines, with nothing added about what this all looked like from the outside! My interpretation is one of three possible options for the 1845 stern: Round the tuck up to the level of the upper counter in Erebus and the transom/stern galleries in Terror; round the tuck up to the level of the galleries and also remove Erebus’s upper counter; deviate from Lang’s 1845 technical drawing and retain the lower counter in both ships, with Erebus likely also retaining her existing upper counter. As I hope I have indicated with linked examples above, the green tracing on the 1836/45 Terror plans are not accurate – but especially not for the larger Erebus! Only the wreck archaeology will determine the true dimensions and precise geometry of either ship’s 1845 stern configuration. I believe that Lang, familiar with what had happened to Terror’s old-style traditional stern during her 1836 Frozen Straits Expedition ordeal – the near fatal damage to the stern timbers – would have followed his general program of propeller installations, and planked the strongest stern he could have into the two ships- to give the vessels the best chance of not being destroyed by Arctic ice. In my plan, I drew in a “quarter badge” element which tails downwards and which would have flanked the original lower counter in Erebus. This is a stylistic decision and also allows me to easily pencil in a lower counter dividing line towards the stern post if I end up being wrong!

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: We would like to acknowledge the assistance of staff at the National Maritime Museum / Royal Museums Greenwich, as well as HMS Terror expert Dr. Matthew Betts, and Jonathan Moore at the Parks Canada Underwater Archaeology Team, both of whom generously corresponded with me about elements of Erebus’s design over the course of my often-ambling 2022-24 correspondence. Their assistance does not imply that they endorse the above interpretations.

Notes:

- This summary of events is drawn from several chapters of John Geiger and Alanna Mitchell Franklin’s Lost Ship: The Historic Discovery of HMS Erebus (Toronto: HarperCollins Pub. 2015). Ryan Harris, Parks Canada’s project lead on Erebus, provided an incredible guided tour of the wreck in October 2014: https://youtu.be/ZxH18XKqt-k?si=OCrC1XHYZa6AfpvC ↩︎

- Earlier expeditions of the 19th Century had used converted whaling ships, but Captain Christopher Middleton’s 1741-42 Northwest Passage Expedition featured the converted bomb vessel HMS Furnace, while Constantine Phipps 1773 Expedition “towards the North Pole” (which a young Horatio Nelson journeyed on) used a pair of bombs, HMS Racehorse and Carcass. Fury did not survive her Arctic ordeal, and, it is hoped, one day this near-sister of Erebus, with earlier Arctic modifications, will be discovered near Fury Beach, Somerset Island, Nunavut. ↩︎

- Michael Palin’s book, Erebus: The Story of a Ship (Random House: 2019), is an essential source for information about all periods of the vessel’s service. The equivalent work for Terror is Dr. Matthew Betts’ HMS TERROR: The Design, Fitting and Voyages of a Polar Discovery Ship (Seaforth pub.: 2023) ↩︎

- Hecla was in fact sold for conversion to a whaling vessel in 1831, and a very good whaler was she! ↩︎

- In technical parlance, Terror had slightly more steep-rising floors. A useful description of the changes to sterns, bows, and sheer in the first half of the nineteenth century can be found in Dr. Frank Howard’s Sailing Ships of War 1400-1860 (Greenwich: Conway Maritime Press, 1971) P271. Howard also mentions an interesting and cautionary issue about interpreting contemporary 19th C. naval plans: The ability to draft accurate technical depictions to represent new design elements on paper lagged behind the innovations themselves. ↩︎