This post commemorates the sailors who perished during Christopher Middleton’s Royal Navy exploration mission to Hudson’s Bay (1741-42).1 It can serve as a Roll of Honour for these early explorers. For the context to this effort to locate the fabled passage to the Pacific in the waters of Hudson’s Bay, please see our post on HMS Furnace‘s unique exploration design. Our next post will argue that Middleton’s ship crews should be considered the first Royal Navy polar explorers (forthcoming).

Throughout the many wars and infrequent peace of the eighteenth century, the Royal Navy expanded into a massive fleet sailing from establishments strategically located along the seaborne trade routes. This growth came at a tragic cost: the human toll of crewing this British “wooden world” was staggering.2 Amidst all this death, it may seem odd to commemorate a dozen seafaring explorers who died in an incredibly remote outpost of British Empire. These were some of the very first deaths in a program of British naval exploration of what is now Canada.3 They would not be the last.

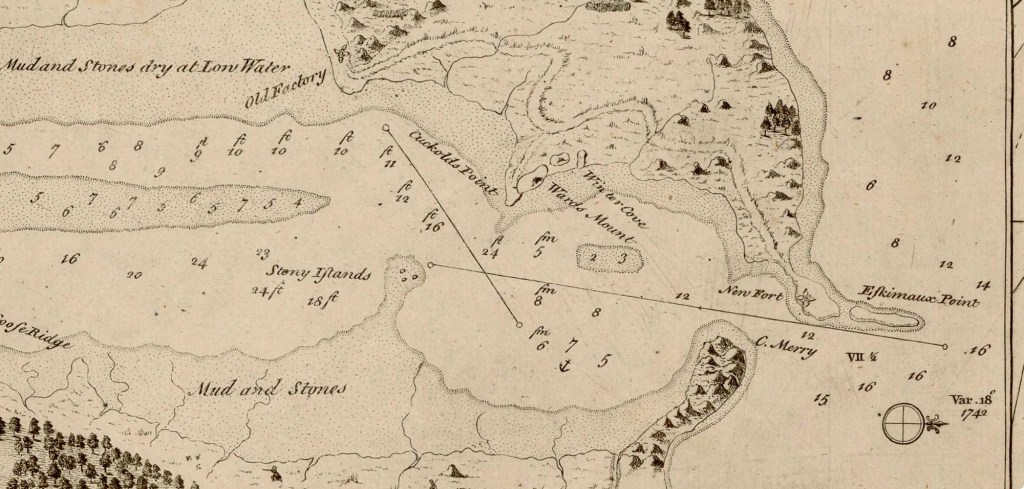

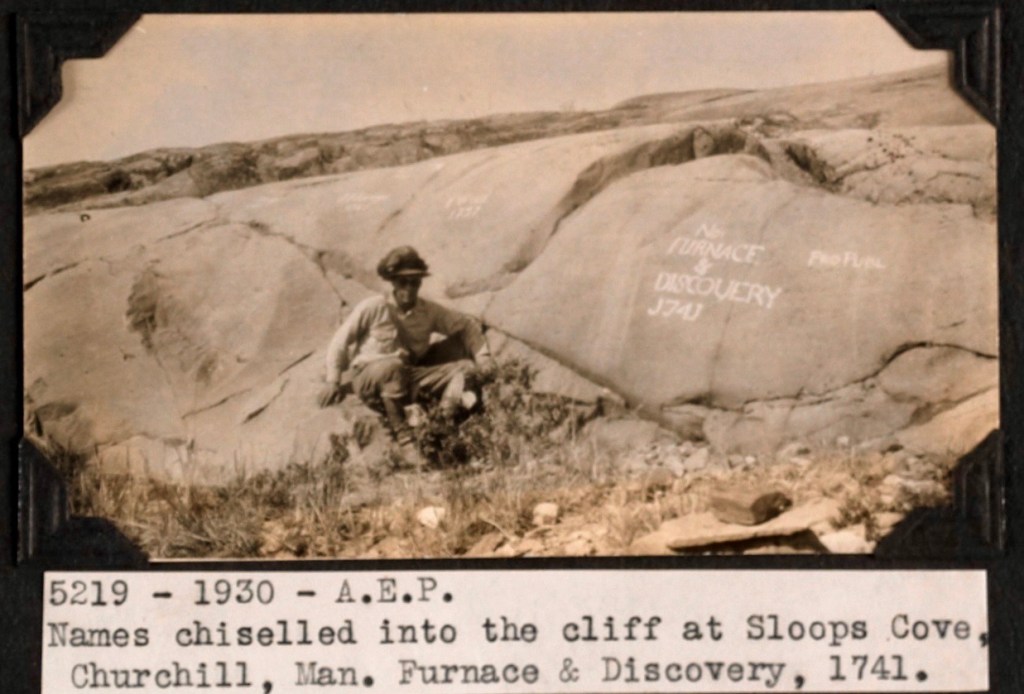

Christopher Middleton’s Northwest Passage Expedition departed the Nore, 8 June 1741. He had experienced significant problems filling out the complements of both his small ships, at their anchorage of Gallions Reach, near Woolwich.4 The seamen who wound up crossing the Atlantic to go looking for a northwest passage in Hudson’s Bay included conscripted men.5 According to their commanding officer, these ninety men were a “crew of rogues.”6 After transiting the Hudson’s Straits into the Bay, a council of officers decided to head for the Churchill River (present-day Manitoba), to overwinter. They would commence their search mission early the next navigation season. At their arrival near the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) establishment, Fort Prince of Wales, crews laboriously cut both ships into secure docks to overwinter in Sloop Cove.

Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Cartes et plans, GE SH 18 PF 123 DIV 3 P 6 via Wikimedia commons.

These northern explorers weren’t equipped with the types of cold weather gear that later expeditions would benefit from. While the officers were lodged at the new fort, crew spent a difficult winter billeted in the “Old Factory,” the former HBC trading post. Several members suffered from frost bite, and the naval surgeons were routinely called over to the old HBC factory to amputate damaged toes before gangrene spread. Worse still, scurvy made an early appearance in the Fall. This dreaded mariner’s disease continued to be a feature of the Expedition all the way back to the Thames, and would eventually claim ten lives. But for Middleton’s desperate attempts to secure fresh meat and vegetables, and the intervention of local indigenous hunters (from the Dene and Cree communities who traded near the HBC Fort and who supplied the expedition with huge quantities of foul), there would have been many more deaths.

I feel it important to compile the names of these early explorers, their dates of death, and the causes, based on the original expedition journal entries and associated contextual documents found in William Barr and Glyndwr Williams’ edited Hakluyt Society publication:

✝William Clark, sailmaker Furnace 28 July 1741 drowned after a fall from fore shrouds in Hudson’s Straits7;

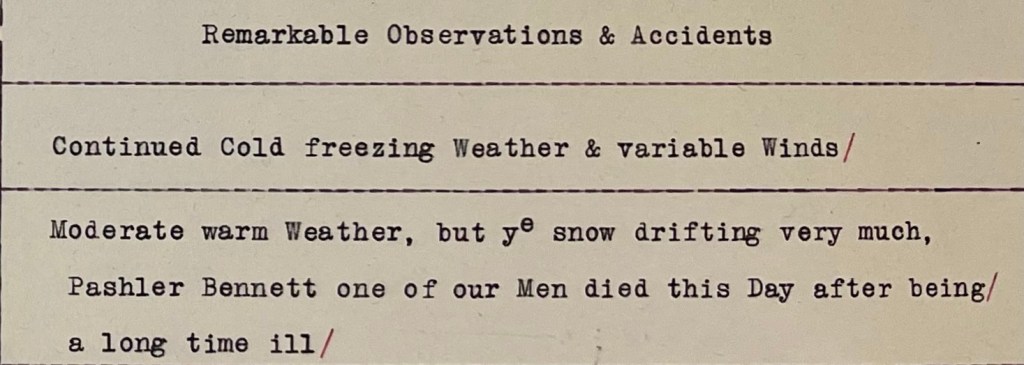

✝Pashler Bennett (or possibly “Paskler Bennet” 29 Dec. 1741 (scurvy at Churchill)8;

✝Christopher Row 13 February 1742 (scurvy at Churchill);

✝Edward Matthews 21 February 1742 (scurvy at Churchill);

✝Abraham Page 13 March 1742 (scurvy at Churchill);

✝John Blair 21 March 1742 (scurvy at Churchill);

✝Henry Spencer 26 March 1742 (scurvy at Churchill);

✝James Thrumshaw 28 March 1742 (scurvy at Churchill);

✝Ralph Pearce Carpenter’s Mate Discovery 9 April 1742 (scurvy at Churchill);

✝Robert Rattery 31 May 1742 (scurvy at Churchill);

✝John Furnix 24 May 1742 (scurvy at Churchill)9;

✝John Matthews Master’s Servant Furnace 20 June 1742 (drowned at Sloop Cove near Churchill)

In some sources Middleton referred to two or three additional deaths. If anyone locates a reference to these other fatalities, or has any information about any known shore burials of the men who died near Churchill, please leave us a comment below.

- The title of this post was inspired by the lyrics of the traditional ballad Lady Franklin’s Lament, which date from more than a century after Middleton’s time. ↩︎

- We need only think of the thousands of the loss of four of Admiral Sir Cloudsley Shovel’s ships and about 2,000 crew in 1717, the Yellow Fever deaths in Admiral Hosier’s fleet at Porto Bello during the 1720s, the 1744 loss of Admiral Balchen’s HMS Victory, with more than 1,150 crew aboard, or the ca. 1,600 members lost from diseases including scurvy at the exact same time as Middleton Expedition on Admiral Anson’s circumnavigation of the World. ↩︎

- These Middleton Expedition posts are careful to refer to the British Naval exploration program (therefore dating it to after the Acts of Union in 1707). I also haven’t encountered any prior official, Admiralty-sponsored English naval missions. The largest loss of life in the Bay, somewhat astonishingly given the toll disease normally took on far-flung expeditions, had actually occurred in September 1697, during the Battle of Hudson’s Bay, when Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville’s French ship Pélican had caused the English 50-gun ship Hampshire to explode, killing its full crew of more than 250 men. ↩︎

- Dates and information about the Middleton Expedition is primarily drawn from Middleton’s 1741-42 journal of HMS Furnace titled “Master’s Log, kept by Christopher Middleton.” Library and Archives Canada holds a fully-transcribed version of the journal, created from the original handwritten copy that Middleton had sent to Arthur Dobbs in 1742 (one of four known contemporary copies created in 1742 from an original that no longer exists). See Arthur Dobbs fonds, MG18-D-4 Volume 4. The daily entries are from March, 1741 until October, 1742. This transcription was created in 1927 by the Public Archives of Canada (overseas) copyist program from the original in the Public Records Office of Northern Ireland, Belfast, where is can now be located at reference D162/37. ↩︎

- Unlike later British naval exploration missions, such as Parry’s 1820s missions or the ill-fated Sir John Franklin Expedition of 1845, the Middleton Expedition was not made up of an all-volunteer crew of experienced professional seamen. During the early 1740s, as a war against Spain escalated into the broader War of the Austrian Succession (with Britain now fighting a naval war against both Spain and France), the Royal Navy resorted to impressment to operate its expanding fleet. ↩︎

- Voyages in Search of a Northwest Passage 1741-1747 Volume 1 The Voyage of Christopher Middleton 1741-1742 Eds. William Barr and Glyndwr Williams (London: Hakluyt Society 1994) Middleton to Thomas Corbett, 16 October 1742. P221. This excellent publication, with introductory information and explanatory notes by Barr and Williams, includes additional information about fatalities which were sourced by Barr and Williams from Lt. John Rankin and John Moore’s journals, as well as HBC official James Isham. The portion of Middleton’s journal transcribed in their work runs from 17 July 1741 18 August 1742. The editors transcribed the copy of the log found at the National Archives (UK) at ADM 51/379. ↩︎

- Located in original journal transcription in Arthur Dobbs fonds at LAC MG18-D-4 volume 4. ↩︎

- The transcribed copy at LAC records the first spelling, while Barr and Williams, who were examining the handwritten copy at the National Archives (UK), recorded it differently. ↩︎

- HBC Factor Isham recorded this death, not Middleton or Rankin (Barr and Williams P169). ↩︎