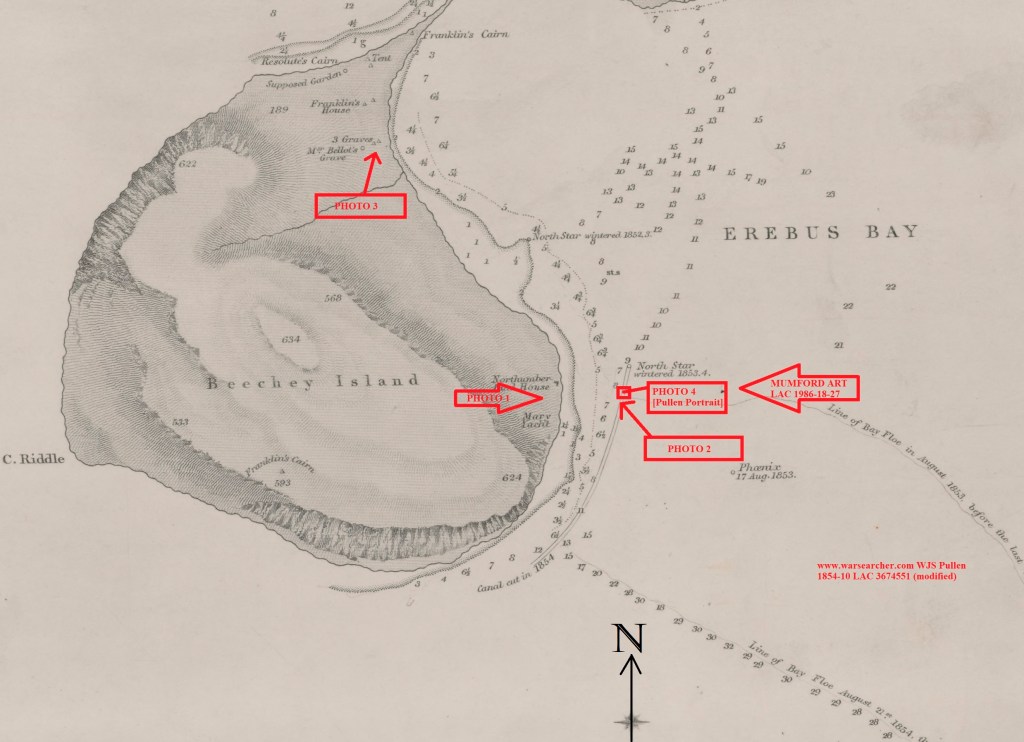

Beechey Island, Nunavut, (Iluvialuit) is an important site connected to both the Sir John Franklin Expedition (1845) and the period of searching for the lost crews of HMS Erebus and Terror. In August 1854 Commander F.L. McClintock captured the earliest known photographic depictions of the Canadian Arctic at Beechey. For anyone interested in this era of Arctic exploration, the ruins, cairns, memorials, and graves can become touchstones to the lost Franklin crewmembers and to the other sites of the ill-fated Expedition. In this post we will travel back in time to the critical moment in the creation of the built environment of the Beechey Island National Historic Site.1 We will also digitally reconstitute an incredible collection that has been dispersed across at least two continents. Join us as we accompany McClintock on his photographic expedition: A tour of Beechey in four amazing photographs!

Arctic history scholar Douglas Wamsley holds in his personal collection two historically important photographs, the earliest depictions of Beechey Island Sites National Historic Site of Canada. These were taken in an era when the crews of five exploration ships – Sir Edward Belcher’s Expedition – were engaged in the most extensive official effort to find the missing crews of Sir John Franklin’s Expedition that would ever be mounted. In their 1996 Polar Record article “Early Photographers of the Arctic,” William Barr and Doug Wamsley identified the photographer of these two views as Royal Navy Commander F. Leopold McClintock (1819-1907).2 They connected the two photos to his journal entries, and dated the first photo as having been most likely taken on 12 August 1854. McClintock – a veritable “go anywhere do anything” phenom of Arctic exploration – had commanded HMS Intrepid.

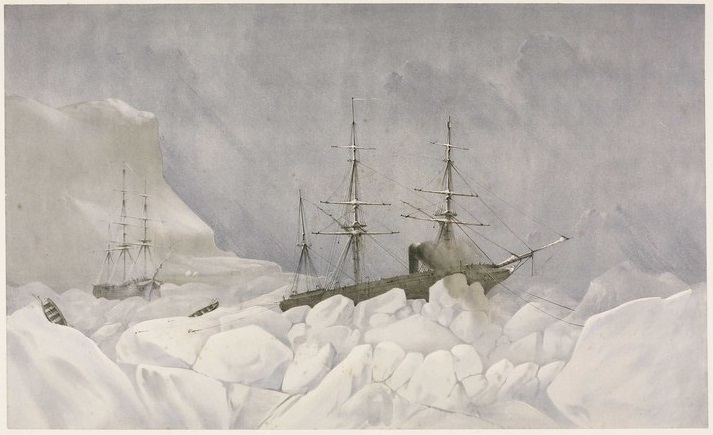

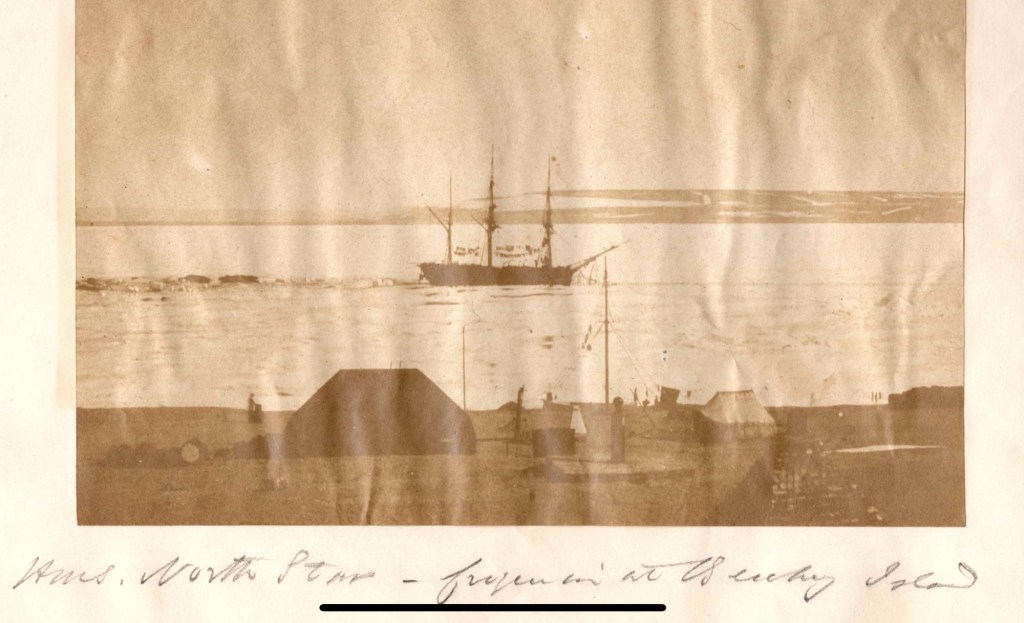

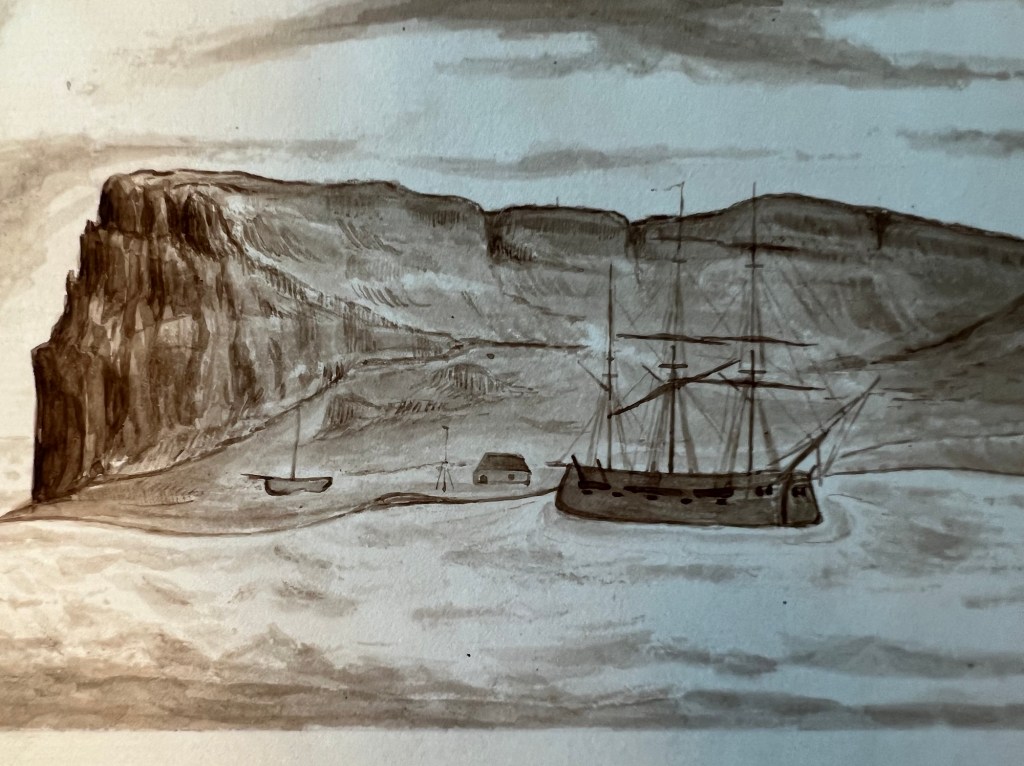

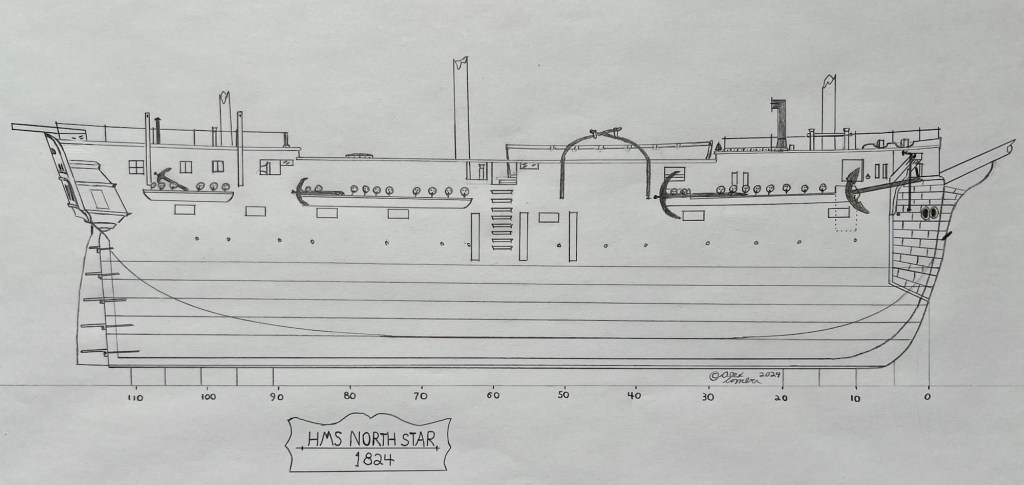

Accompanying HMS Resolute (Capt. Henry Kellett) as a steam tender on the western arm of the Belcher searches, both ships were beset in ice, with no guarantee crews could extricate them. The northern arm of the searches also being iced-in, Belcher ordered Kellett and McClintock to abandon their ships during May 1854 and return to Beechey. After sledging back eastwards over the still-frozen channels and straits, they were welcomed with cheers from the crew of HMS North Star, the Expedition’s depot ship, which was under the command of William John Samuel Pullen.3 Resolute’s Assistant Carpenter, William Mumford, worked up a view of the overall scene which they encountered on their arrival, 28 May 1854. This watercolour helps us contextualize McClintock’s subsequent photographic expeditions. North Star is shown locked in ice and pointed northeast into the Bay.4

Having returned to Beechey without a ship, and not being then engaged in long-distance sledging (which he excelled at), McClintock decided to take up the role of “quasi-official” Belcher Expedition photographer. Before the Expedition departed England, HMS Resolute’s surgeon, William T. Domville, had originally been trained on taking photographic negatives using a camera obscura and developing them into prints using the calotype process. Domville took a few early photos in Greenland in 1852.5 It appears likely the camera was then stowed away for two years. Wamsley and Barr note that McClintock began taking pictures in early August 1854, and soon gained confidence with the apparatus and the complicated chemical treatment and development process.6 Despite the incredible challenges involved in producing an 1850s photographic record in the Arctic, McClintock even tried his hand at portraiture, capturing some of his companions (more on that below).

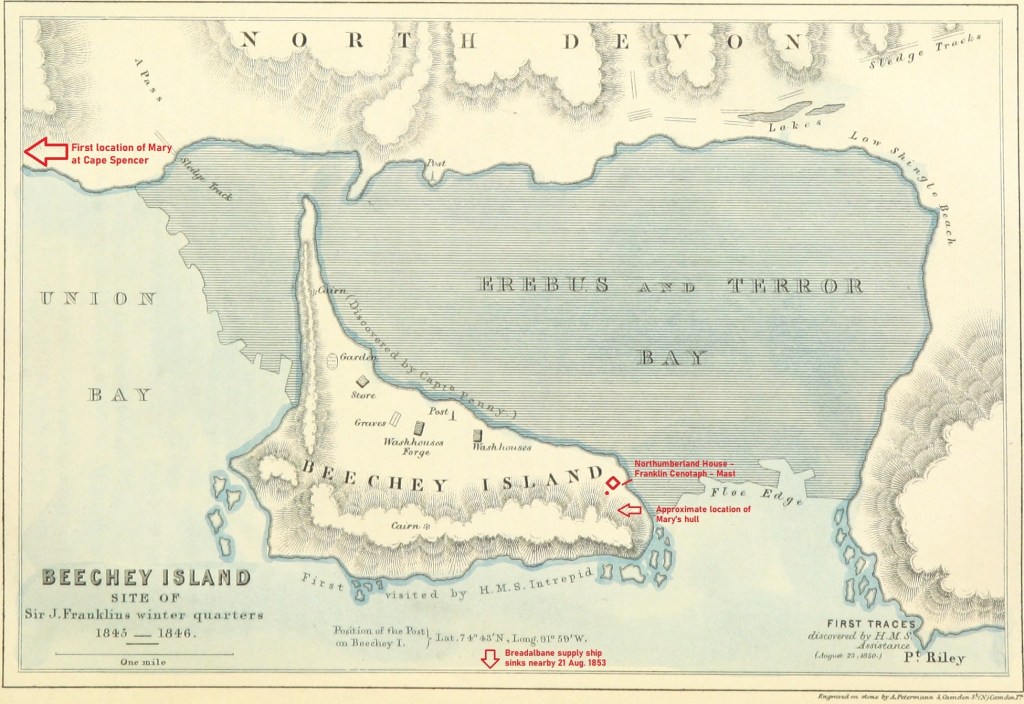

Let’s journey back to Beechey as it existed then, to accompany McClintock on his photographic excursions. In early August 1854 the explorer, now firmly in command of the northernmost example of one of Her Majesty’s cameras, struggled west across the uneven ice from HMS North Star towards the Island. He most likely led a small shore party to assist him in hefting the heavy camera and tripod. Having ascended the rocky beach, past some of the new construction the North Star crew had completed over the last two years, he tucked himself under the soaring, fortress-like cliffs, and pointed the apparatus towards the east, back across Erebus and Terror Bay (see the annotated map above).

Laid out before him was an incredible Arctic vista: The frozen bay stretched into the distance, with an almost incandescent glare rising off the ice. Above the far shore, the bulk of Devon Island (Tallurutit) extended out towards Cape Riley, whose grand headland would be just to the right of the frame. It was a view that the lost men of the Franklin Expedition would have been completely familiar with, as they had overwintered near this same spot 1845-46. The actual moment of capture was probably not attended with much drama–no flash like a cannon’s discharge, no crashing report like a musket volley fired over a crew members’ burial. Yet by removing the lens cap for a few moments, McClintock had yet again triumphed in the northern latitudes. As light passed through the lens and into the camera chamber, an image was projected and recorded onto a sheet of chemically-treated, light-sensitive writing paper placed at the back of the camera. Another wonder of the Victorian age had arrived in the Arctic! The process pioneered by William Henry Fox Talbot would have involved McClintock treating the paper with noxious chemicals before leaving North Star, perhaps having started the first washes and sensitizing steps in an improvised darkroom deep in the ship (sheltered from the 24-hour sunshine). The stages of photography and print-making can be seen in the youtube tutorial from the Victoria and Albert Museum:

Opening the lens allowed for the image of this unique scene to be transmitted onto the sensitized paper that had been loaded into the back of the camera.7 At a later moment, another treatment process in the darkroom was used to develop this now-exposed negative and fix the image in place. Through a similar (though simpler) chemical process used to prepare calotype negatives, another sheet of sensitized paper would be physically pressed beneath the negative and exposed to sunlight via contact printing. This would create a positive version of the image. These positive variants are commonly known as salted paper-prints. They display a characteristic fuzziness – from the paper-to-paper printing process- while the printed image takes on sepia-like tones.7 Here was the great advance in photography over daguerrotypes: a film developer could use the process to create MANY salted paper-prints from the single calotype negative.

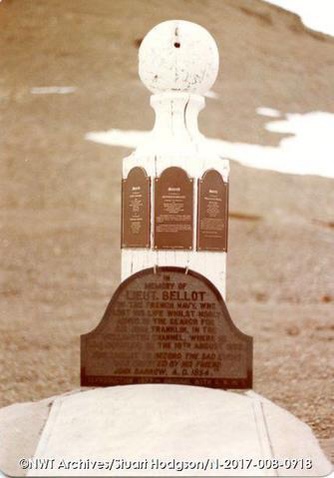

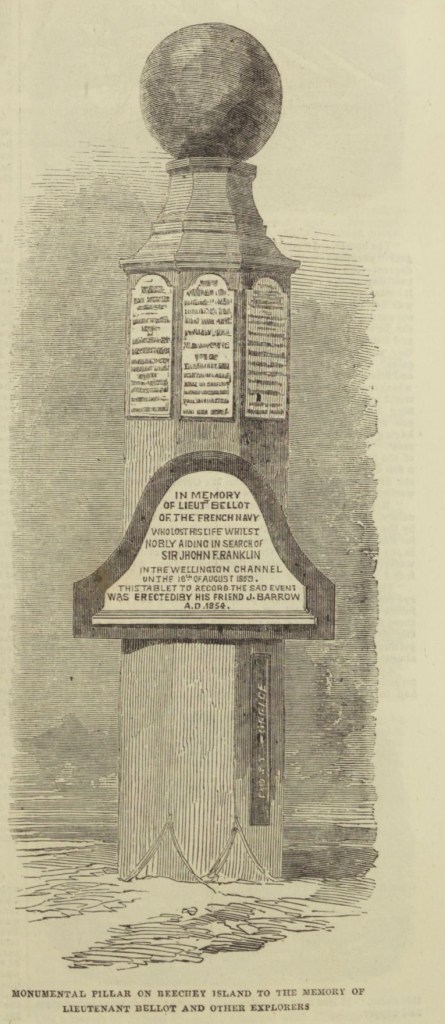

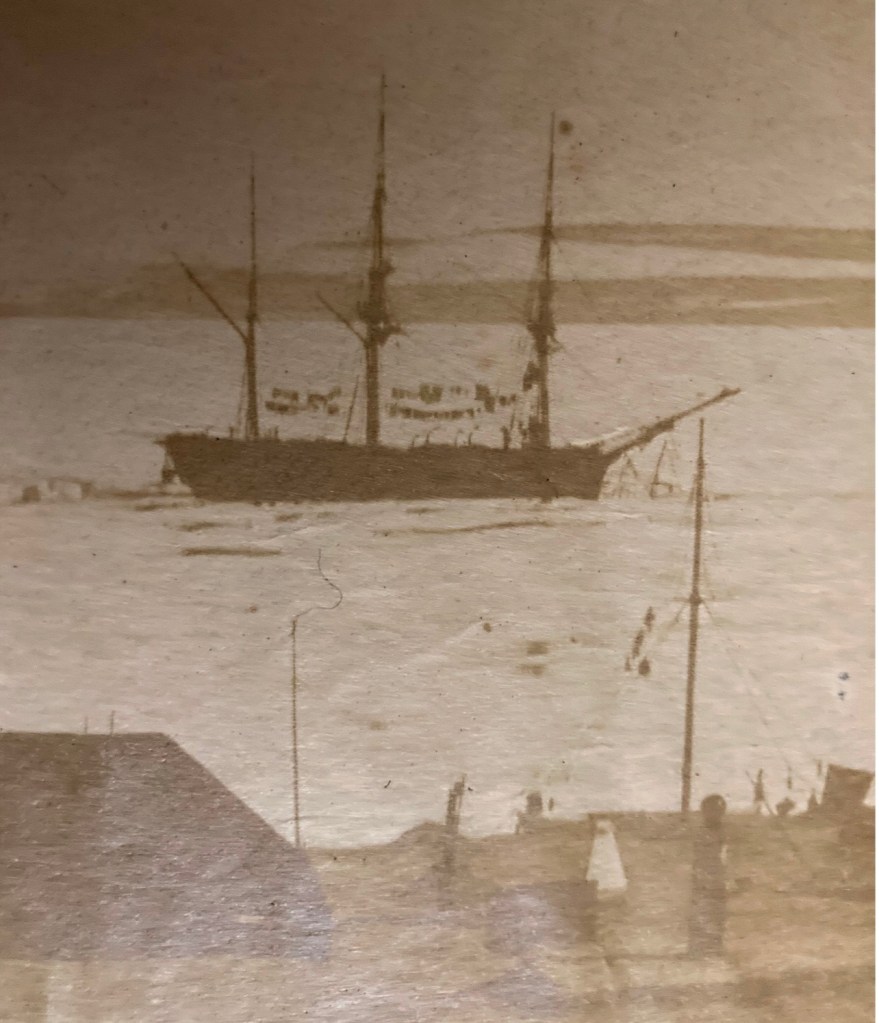

On this first print, Northumberland House appears in the left foreground as a squat roofed-over structure. This depot or Arctic storehouse had been built over the 1852-1854 summers by the crew of North Star. Captain Kellett, McClintock, and the Resolute and Intrepid crews had built a similar structure at Dealey Island.8 The house had not yet been ringed by a low wall to the north and west, which is much in evidence during Allen Young’s 1875 Pandora visit.9 To the right, a signal mast – complete with stays and a topmast – is rigged near to the shoreline, with another shorter staff standing nearer to the House.10 In the near foreground, the brand-new monument or “Franklin Cenotaph,” is conspicuous, wearing its original somber coat of black. It had been shaped by Mumford and the other carpenters from the pawl bitt of the lost whaling ship McLellan’s windlass, and raised at the very end of July. The photograph may have actually been taken on the first or second of August, when crew were paving round the monument, but had not yet finished walling in the casks on the west and north sides of the House.11 This is the only image we will likely ever see of this important cenotaph before the Joseph René Bellot memorial was affixed to the front of the pedestal at the end of that August.12

There is a pyramid of tins in the right foreground, while a tent (most likely a marquee tent raised in mid-July to prepare the site for the arrival of Captain Belcher from the still-beset HMS Assistance) had been pitched to the right. Just off the beach rests the considerable bulk of a three-masted sailing vessel in good focus. A motionless ship sailing a static sea makes for an ideal subject, given the technical limitations of 1850s photography.13 North Star was locked in ice, with masts all up but no sails bent on the yards. Though the scene has few crew members depicted, one gets the sense of industrious bustle ashore from casks lined up on the far side of Northumberland House, and what appears to be a line of boats aft of North Star. Wamsley and Barr noted that there was visible evidence at the bows that crew had commenced cutting the ice around the bows with ice saws. By the crew’s exertions cutting and parbuckling the ice, North Star had been turned with her bows now pointing south towards the open waters of the Barrow Strait.

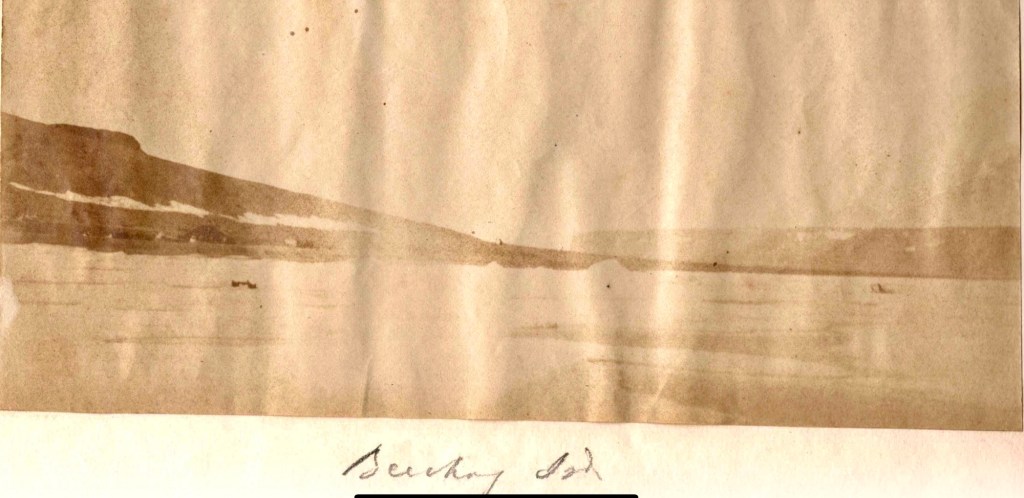

The second photo used in this post was taken from onboard the North Star, in a northwesterly direction. It shows a distant and indistinct view of the shores of Beechey Island and the land bridge stretching around the bay to Devon Island. Northumberland House can be seen on the near shore. The House appears at a greater distance from the ship than in the first photo. It seems reasonable to assume this was taken days later, as North Star was gradually hauled south towards the edge of the ice. The ice appears disrupted in the foreground, suggesting the route the crew had already cut. Some black flecks at the very center of the photo may hint at the Franklin crewmembers grave boards, our next stop!

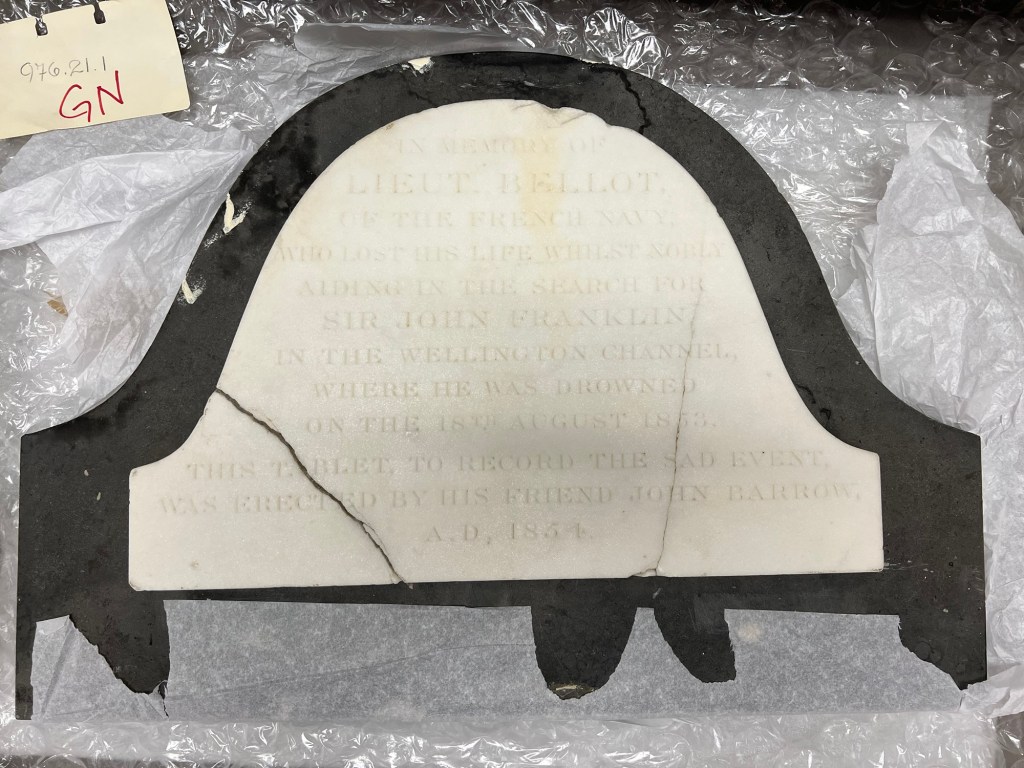

Up until a few years ago, these two prints comprised the entire extent of McClintock’s Arctic photography. That has changed over the last few years, starting with the digitization and uploading of a another salted paper print of the Franklin crewmembers’ graves located in the Gell family album at the Derbyshire Record Office (DRO). Franklin scholar Russell Potter has written an interesting contextual post about the discovery of this mysterious photograph, which we will identify here as photograph #3.14

It now seems likely that McClintock did what any modern visitor to Beechey equipped with a camera would do: He walked about 1.5 kilometers up the beach and snapped the first known photo of those famous graves, which, after all, contained the only Franklin crewmembers that any searchers had (as of 1854) yet located.15 Two important details link the McClintock prints to this mysterious DRO print of the three Franklin crew members’ graves: Erebus and Terror Bay (the shoreline to the right) is a blinding expanse of frozen ice, but there is no snow on the rocky ground.16 The dimensions of the three prints are also similar, which is consistent with having been created by the same camera apparatus.17 Since Domville is believed to have stopped taking photographs after the departure from Greenland, there is also, to date, no other known photographer using a camera combined with the calotype development process that was active in the area at this time.

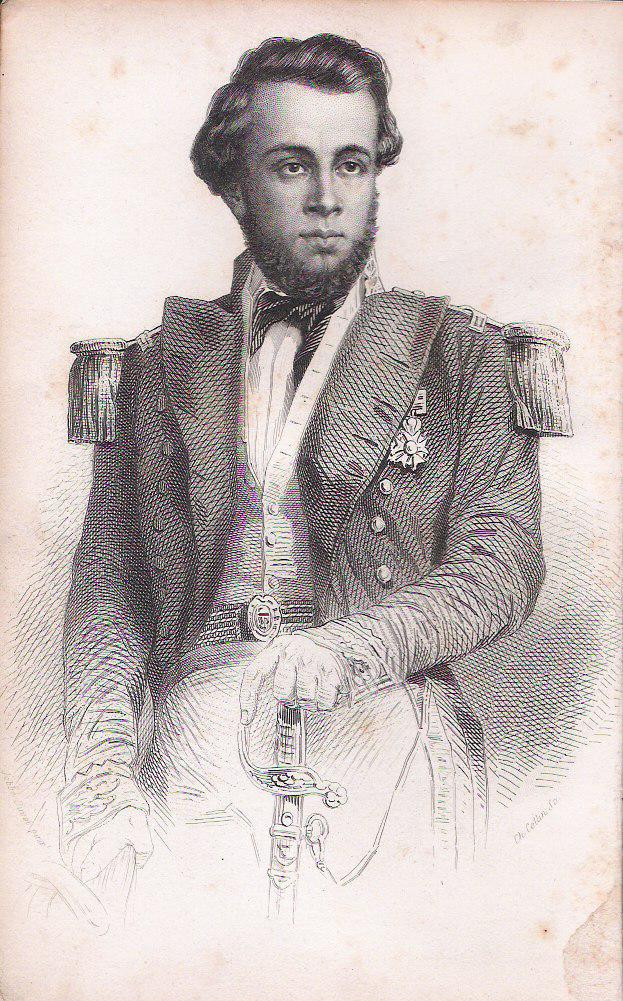

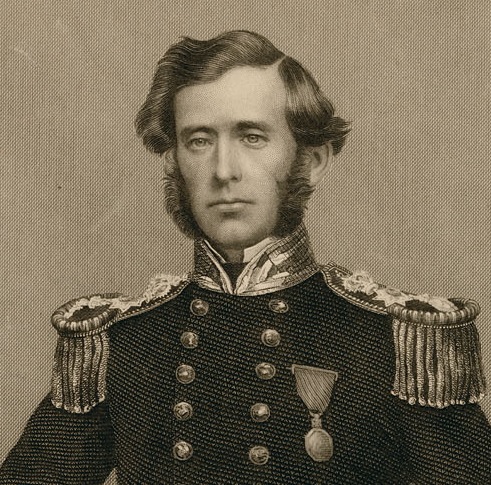

Wamsley and Barr noted (in 1996) that none of McClintock’s calotype portraits from mid-August 1854 had ever been located.18 I believe we may now also have one example of this series, which, according to the journals of both McClintock and George Ford (ship’s carpenter from HMS Investigator), were taken on 21 August 1854, on the deck of North Star.19 Recently, an item came up for sale on ebay with a strong Beechey 1854 connection: A seated portrait of an officer of the mid-nineteenth century Royal Navy (photograph #4). Notations below the print indicate it to have been taken in 1850 aboard HMS North Star, before “Father” departed on an Admiralty search for Sir John Franklin in the Arctic region. “Remembering the Franklin Expedition” Facebook group member Conner Nelson noted a strong resemblance to Cmdr. W.J.S. Pullen.20 The portrait appears consistent with an unwaxed positive, salted paper-print, from a calotype negative taken using the camera’s portrait lens setting (or possibly a separate lens formatted for portraits).

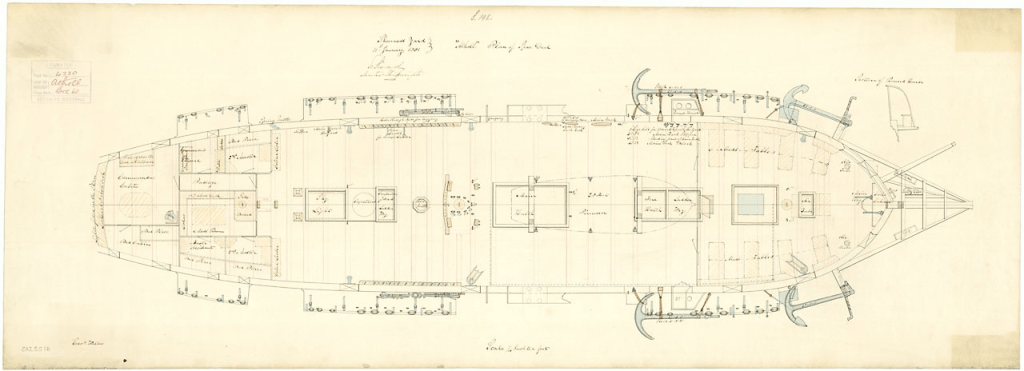

I believe this portrait was most likely taken onboard North Star by McClintock in that high Arctic summer of 1854. I also believe it depicts W.J.S. Pullen’s brother, Thomas. W.J.S. had been appointed Commander while away on his first expedition searching for Franklin in 1850, two years before he was appointed to command North Star. For this new search effort, he would be accompanied by his younger brother, Thomas C. Pullen, who served in the role of Master (a senior warrant officer). Though I have not been able to examine the portrait in person, it is unique from the contemporary image that the engraving of the Belcher Expedition commanders is based off in The Illustrated London News.21 In contrast to his older brother, T.C. appears to be the right age. He is depicted in the pre-1856 undress uniform of an officer.22 Masters in the Royal Navy had recently been granted the authority to wear the epaulettes of a junior officer, which in this era were unadorned with the distinctive anchors, crowns, or pips worn by commanders and more senior officers. Where precisely was this calotype portrait taken? My familiarity with North Star’s layout and plans leads me to suggest one likely place: Just to the side of the ship’s wheel, tucked under a “poop” deck that, uniquely of all Belcher Expedition ships, North Star was equipped with.23

Though the louvered door is similar to the style of door found in an earlier illustration of North Star‘s flag locker (depicted prior to the James Saunders’ supply expedition this was located directly over the transom at the very stern), it is my belief this door led directly into “Officer’s country” – the decked-over passage and cabins at the stern that held the berthing for the Pullen brothers and the other officers.24 This would have been an ideal setting for McClintock to utilize a portrait lens (or a dual setting lens like the Chevalier lens fitted to the above Science Museum, London, artifact).25 The series of portraits captured by McClintock on 21 August may have been intended for a celebratory purpose: on that day, North Star crew finally cut through or blasted with explosive charges the final stretch of the more than 1,000 yard canal southwards and arrived at the edge of the floe. North Star had survived two punishing winters at Beechey, and could now escape the Arctic. T.C. Pullen’s 1854 journal entries record his titanic efforts – despite illness and profound weariness – to spur his crew on to free the ship from an icy grave.26

The depot ship was now burdened by supernumeraries from five abandoned Franklin search ships: Investigator, Resolute, Assistance, Intrepid, Pioneer. Just before departure, a strange sail to the east resolved itself into Edward Augustus Inglefield’s trim steamer, HMS Phoenix and the storeship Talbot. Onboard the steamer was the distinctive plaque to the memory of Bellot, to be affixed to the front of the monument, and – relevant to our photographic survey – a new generation of camera: a glass-plate camera employing the vastly superior wet collodion process. The age of the calotype photographic process had arrived and now departed from the shores of Beechey Island! Thank you for accompanying McClintock and I onboard HMS North Star, and out onto the rugged landscape of Beechey Island, these seventeen decades ago!

Acknowledgements: I would like to thank Douglas Wamsley for his support and advice and for reviewing an early version of this post, and Russell Potter for facilitating our contact last December. Library and Archives Canada Audiovisual Specialist Anitta Martignago generously shared her expertise about calotype negatives and salted paper-prints: She has actually taken and developed calotypes herself! Sylvia Wright, a direct descendant of Sir Leopold McClintock, also provided feedback. The Derbyshire Record Office staff provided additional information and kindly consented to the usage of the Beechey grave print.

ENDNOTES:

CLICK FOR ENDNOTES