In this post I will describe the “boat place” boat at Erebus Bay that searchers looking for the lost Sir John Franklin 1845 Expedition came across in 1859. A later post will show my effort to construct a small model of this unique and sadly-fated boat, and propose some likely dimensions of the full complement of Franklin boats.

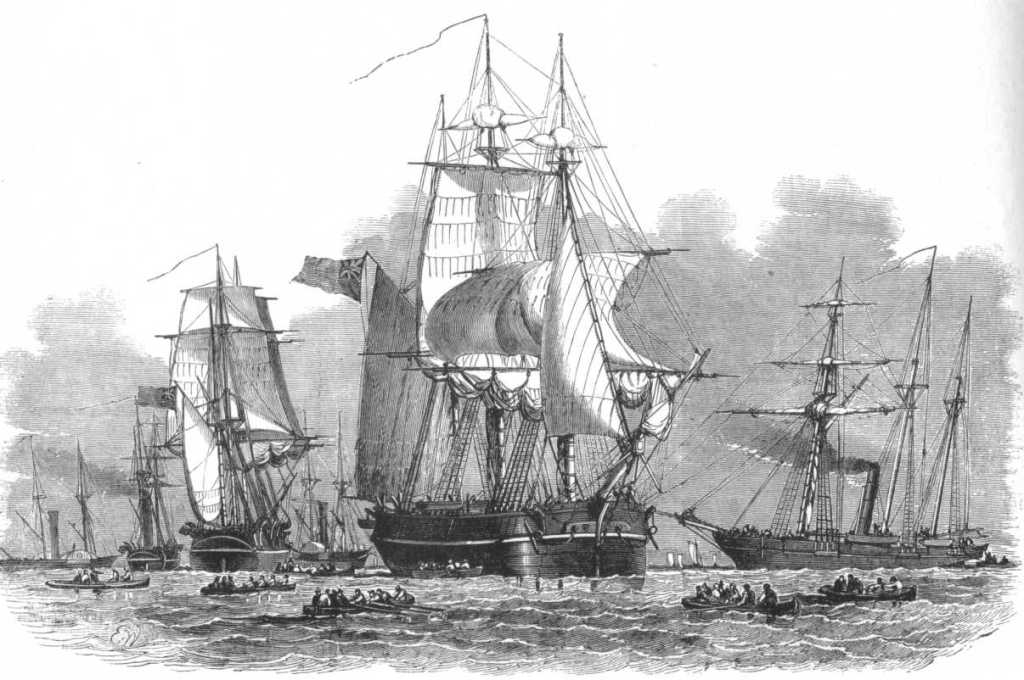

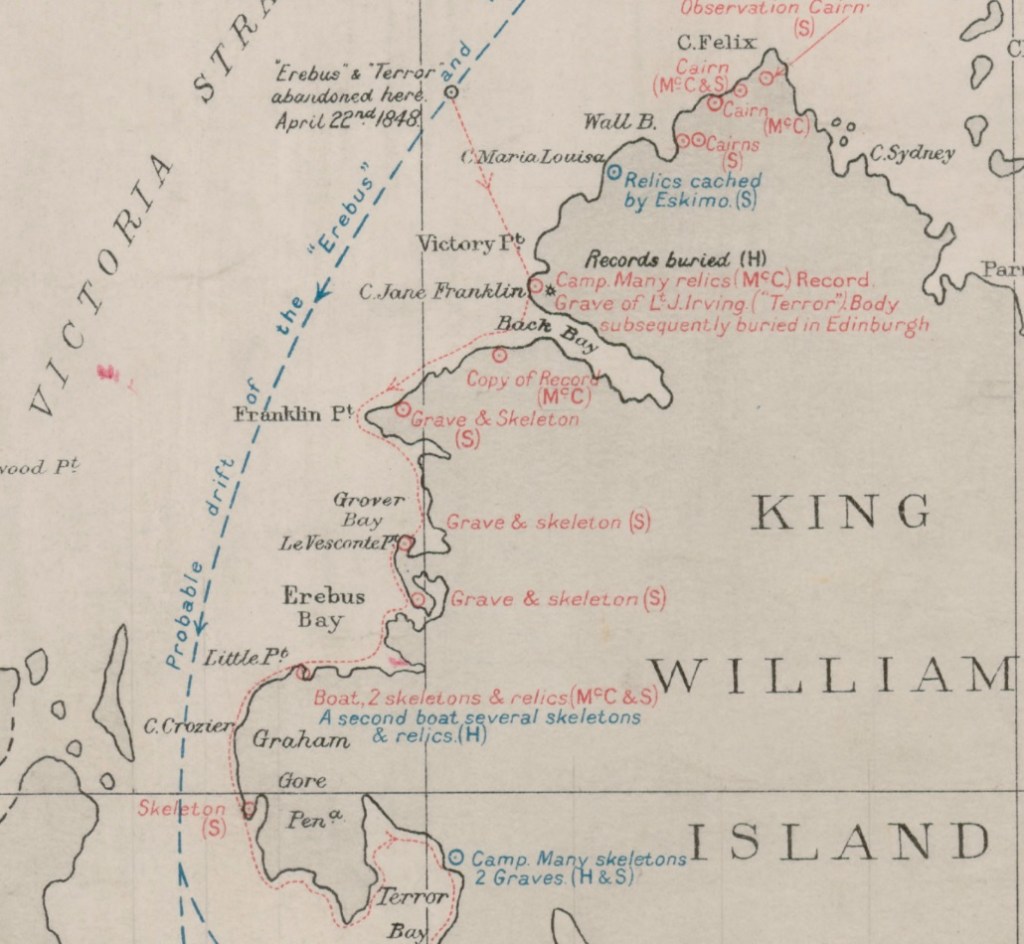

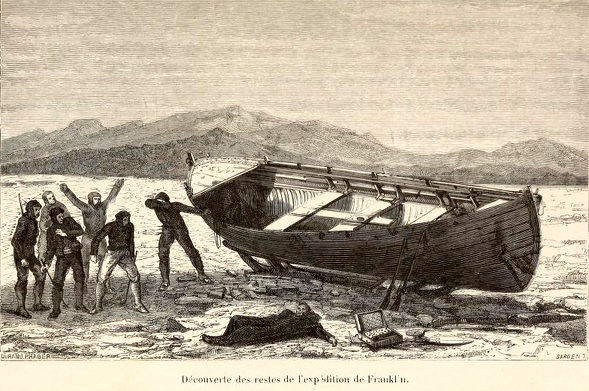

On May 23rd, 1859, at a wide bay on the frozen western shores of King William Island, a group looking for the lost Franklin Expedition found something incredible: A large boat on a sledge. Fourteen years after Franklin’s two ships had left Greenhithe, England, searchers had finally arrived at “ground zero” of the Franklin Expedition escape saga. They were a decade too late. Quartermaster Henry Toms and Carpenter’s Mate George Edwards – both members of Lt. William Hobson’s detached sledge party searching the coast as part of Francis Leopold McClintock’s Franklin search expedition – first spotted something odd projecting out of the snow as they scouted ahead of their mates.1 Closer examination revealed it to be a wooden stanchion, hanging like a beacon over the curved outlines of a gunwale in the high drifts of snow – beneath their feet was the ghostly outline of a large boat.

The next morning Hobson’s group began in earnest a two-day process of clearing out the site and inventorying an unusual assortment of artifacts. That stanchion also marked a gravesite – the resting place of at least two unidentified Royal Navy crewmembers who were entombed within the hull. McClintock’s sledge team arrived a few days after Hobson had departed. His published description of what he called this “melancholy relic” is the standard account of the site.2 But Hobson had also drafted a report on his sledge team’s discoveries, which included a detailed description of the boat. We are indebted to archaeologist Dr. Douglas Stenton’s work resuscitating Hobson’s report about his journey from obscurity. Stenton’s publication of the report provides important additional details to help explore the boat place.3 Since Hobson’s team had excavated the snow from the boat and examined the objects found therein, the site had already been altered before McClintock’s party reached it. For a detailed list of the interesting and unusual contents of the boat, please see Russell Potter’s Visions of the North blog “The Boat” on the topic. My interest here remains focused on the boat itself.

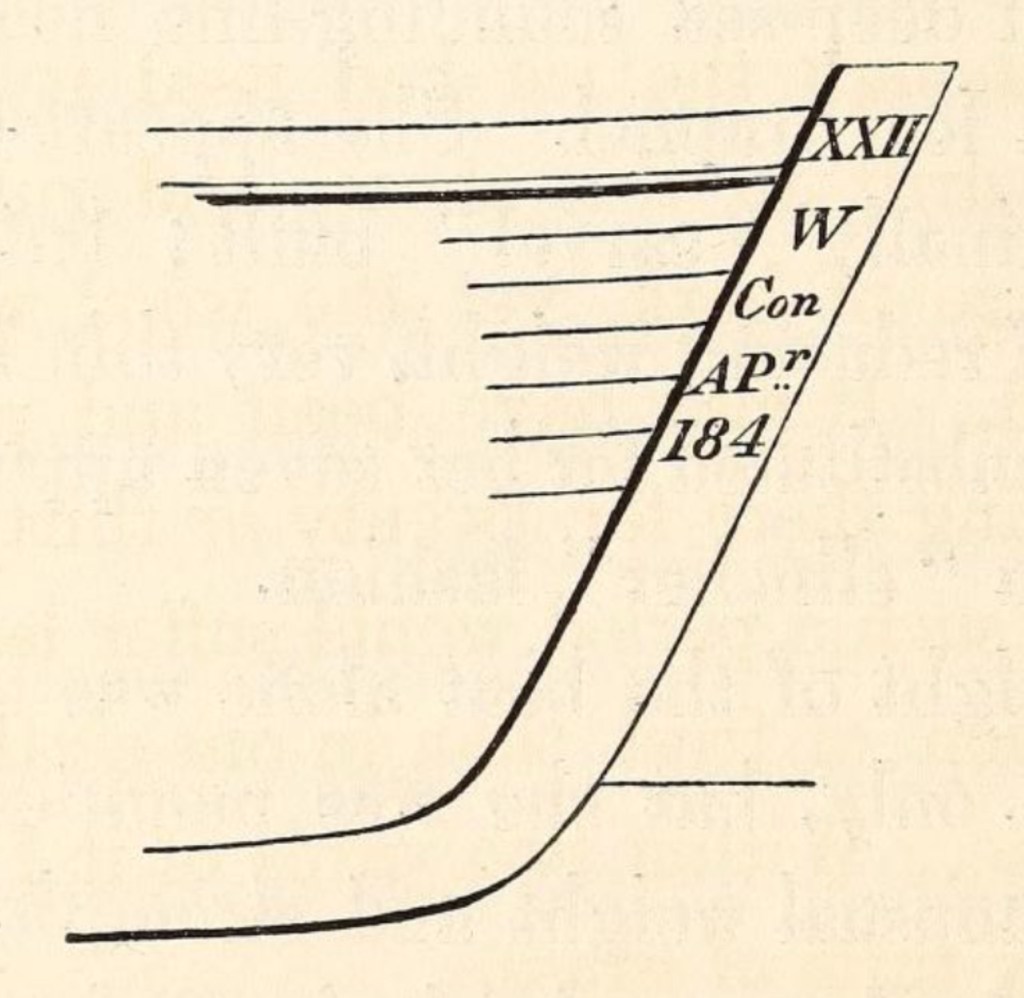

The Erebus Bay find remains the only Franklin Expedition boat and sledge, originally encountered reasonably intact, whose appearance and contents were described in detail. Its importance is tied to the slightly earlier discovery by Hobson’s party of the Victory Point record, in a sealed cylinder in a cairn about 60 km northeast. An update to a routine Admiralty form mentioned the abandonment of the long-beset ships, and recorded captains Crozier and Fitzjames’s intention to mount a desperate trek with their ailing crews towards Back’s Great Fish River. The note had no specific information about how they planned to cross the vast distances involved. The Boat Place discovery seemed to illustrate the mechanism of the evacuation plan: Crew members would use drag ropes to man-haul boat/sledge combinations down and around the coastline of King William Island. They would then unship the sledges and navigate the boats to the mainland and down a treacherous river towards a still-distant fur trading post. We don’t know how this plan changed as they struggled along, losing more men, and abandoning more boats. Some of the last of a group of weary men laid down to die, under another boat, on the mainland at Starvation Cove.

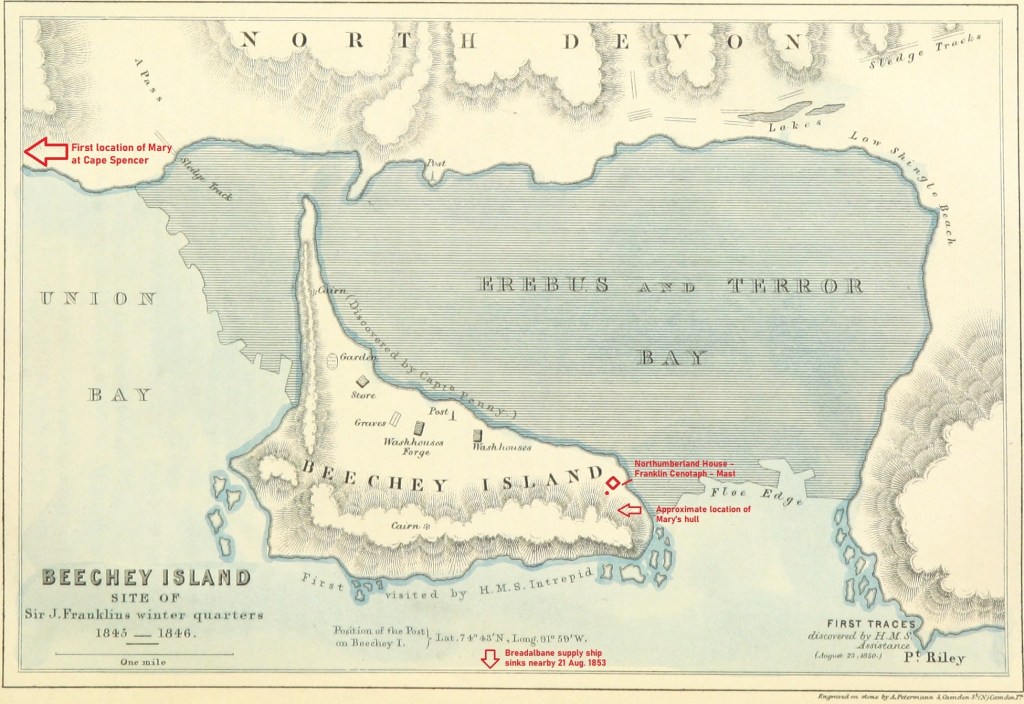

Back at Erebus Bay, the 28’/8.5 m boat was found just above the frozen shoreline. It listed dramatically down to starboard. A hole may have allowed wildlife – bears or scavenging foxes – access on the low side. Both boat and heavy sledge were oriented back towards the northeast, though if that was by intent (to return towards the ships), or by happenstance, no one can say. McClintock commented on both the boat’s lightness, and the sledge’s weight. He estimated the weight of the boat to be about 700-800 lbs while the sledge could have been as much as 650 lbs (the average weight of a 28-foot whaling boat, by contrast, was about 1,000 lbs).4 His observations were informed by his great expertise in sledging, acquired during his participation on this and earlier expeditions.

The boat had been modified by the ships’ carpenters – the square transom at the stern had been removed and the boat was now pointed or “sharp” at both ends, with a curving stem and sternpost, like a broader, deeper version of the two ships’ whale boats. The “carvel” planking (flush-edge-to-edge) of the top strakes of the hull had been replaced and lighter fir “clinker” planks (overlapping) re-laid in their place. An ingenious washcloth design of canvas was fitted in the place of the heavier washstrake boards. The set of six paddles – cut-down oars converted with larger “add-on” blades – indicate that the boat had been converted for inland/river navigation.

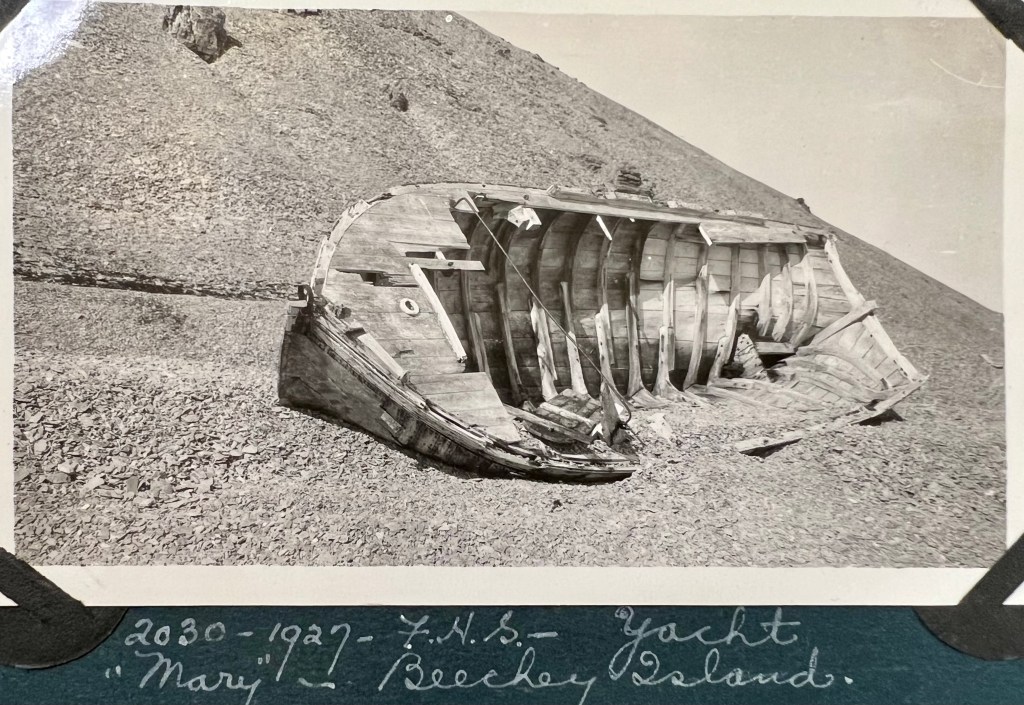

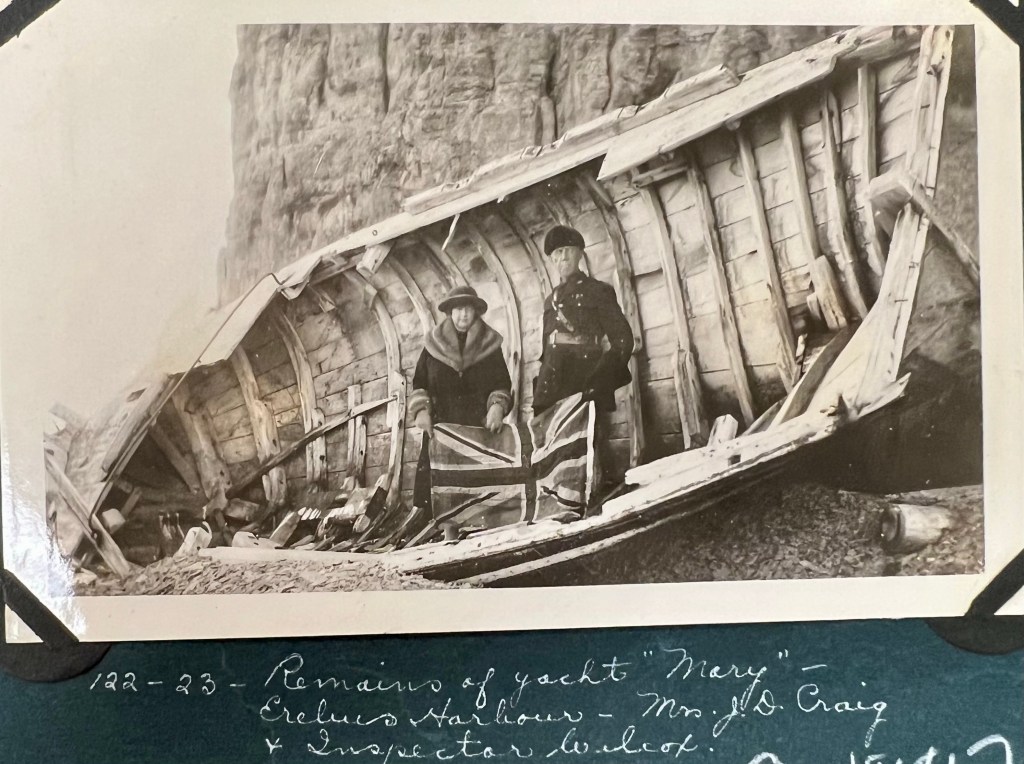

The distinctive stem of the boat was sketched by McClintock. This was recovered two decades later by American Franklin searcher Frederick Schwatka, who, while looking for records, was leading the first expedition on King William Island that encountered the sites in the summer, not under cover of snow and ice.

According to Inuit oral testimony, there was at least one other abandoned boat with many more skeletal remains that was located nearby.5 Both boats were dismantled in the early 1860s for their useful materials and fittings. Following the initial recovery of some artifacts, the dismantling, and Schwatka’s later removals, only archaeological traces and a memorial with bone fragments remain at the site – the last vestiges of a melancholy relic.