🎶In Baffin’s Bay where the whalefish blow, the ship that’d first seen Franklin come, last saw him go.🎶

The Hudson’s Bay Company merchant ship Prince of Wales transported the Arctic explorer John Franklin from England to Hudson’s Bay in 1819 – to command his first expedition to explore the high latitudes of North America – and was also one of the last ships he encountered as he sailed west in HMS Erebus leading his final, ill-fated expedition of 1845.1 Let’s explore her interesting history, picking out those connections to Sir John, and his fellow explorers, who searched far and wide to determine his fate.

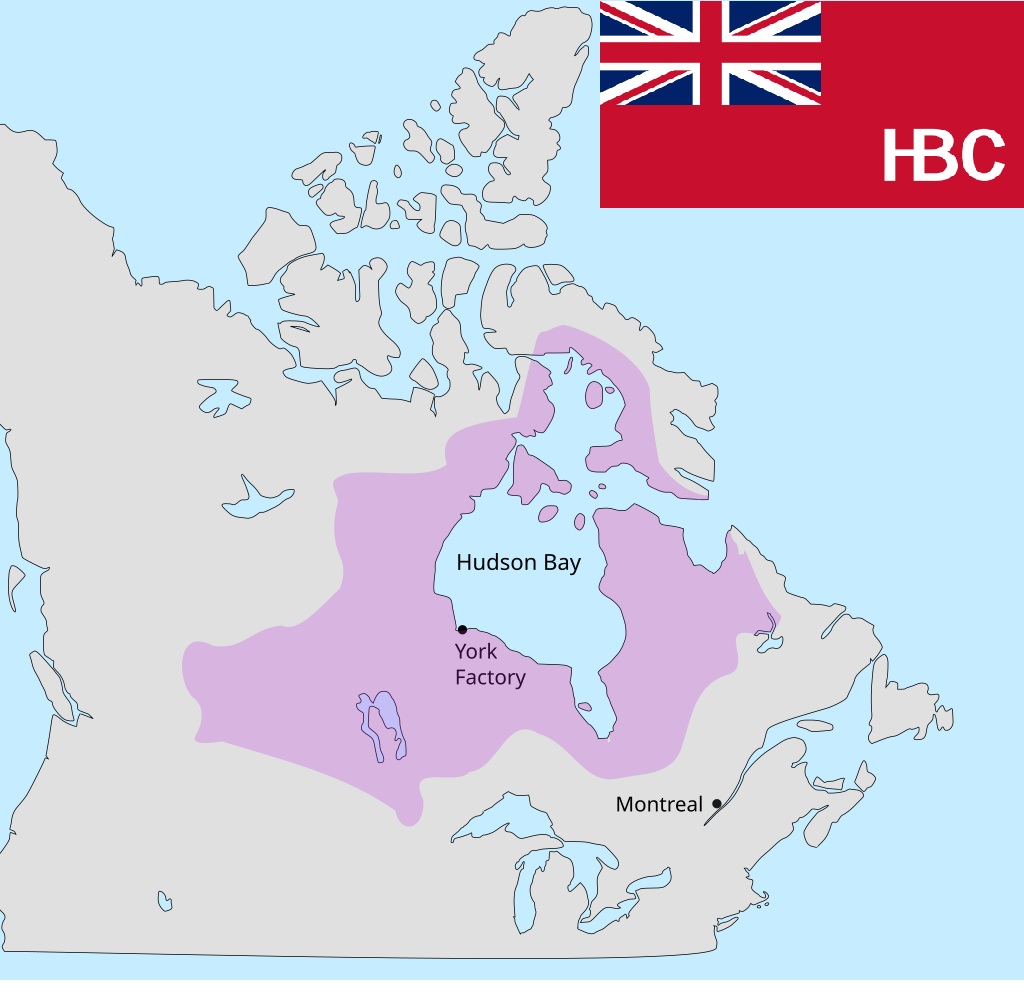

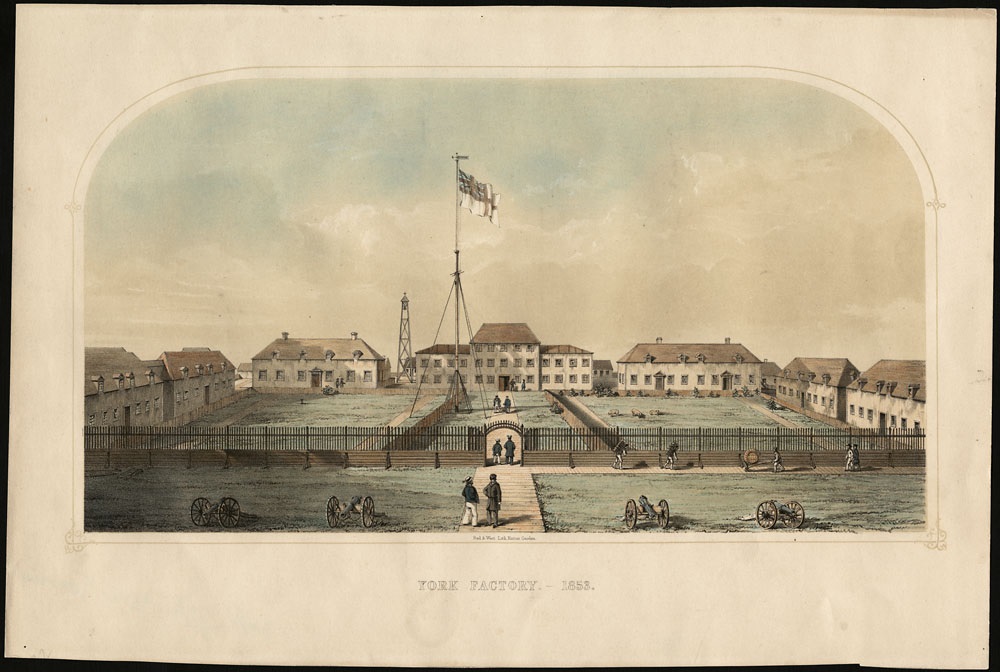

The Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), originally incorporated by Royal Charter in 1670, became a vast mercantile empire that dominated the North American fur trade to Europe.2 Demand for high-quality furs, and especially beaver pelts, increased through the 18th Century as fur products including clothing and hats were in high demand. By the mid-nineteenth century the HBC held monopolistic trading concessions in this chartered territory of “Prince Rupert’s Land” – a large swath of North America that included the traditional lands of a many groups of indigenous peoples. An intricate inland transportation and communication network connected indigenous communities, whose members hunted, trapped and skinned the animals to exchange for trade goods, with the middlemen, voyageurs, traders, and other company personnel.3 The HBC managed a network of trading posts – called “forts” or “factories” on the Bay, along inland waterways, and in the interior.

Starting with the first commercial venture, which involved the tiny Nonsuch ketch carrying a load of beaver furs from the Bay back to England in 1669, merchant ships were vital to the HBC’s long-distance fur trading. Company directors acquired a fleet of ships to resupply the isolated posts, transfer Company personnel, and transport the furs back to Europe for sale. It was a hazardous trade: In addition to all the regular dangers of navigation, there were icebergs, bergy bits, growlers, pack ice and land floes that could fatally nip a hull. A ship could be beset for so long that the crew had to abandon it to search for rescue.

Prince of Wales was completed at Rotherhithe, London, in 1793. In contemporary depictions, we see a stout vessel with a three-masted ship rig. She was fitted with a single row of stern galleries and displaced 351 tons. At this time, the French Revolutionary Wars were spreading beyond Europe. She received a heavy armament of 9-pounder cannon and would occasionally cruise under Letter of Marque – as a privateer operating against Britain’s enemies. The ship’s regular route involved yearly voyages from England through the Hudson Strait, and down into James Bay, the southern portion of the immense Hudson’s Bay.

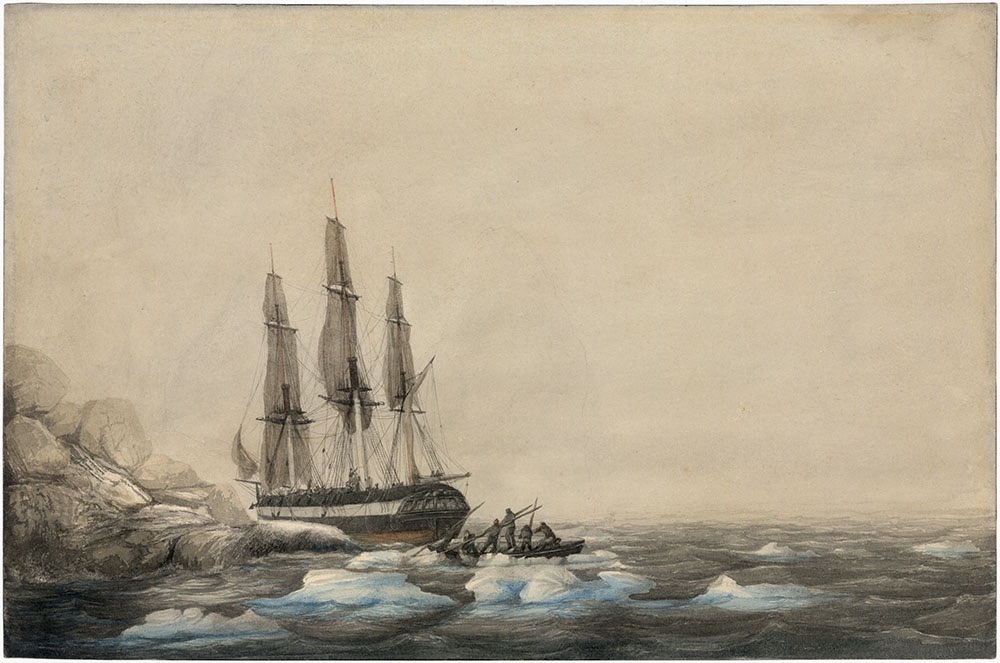

Prince of Wales had already served a quarter of a century when a small naval party, under the command of Lt. John Franklin, boarded the vessel for transport to the Bay. Franklin – who had recently commanded the second ship in David Buchan’s Spitsbergen Expedition towards the North Pole– had been ordered by the Admiralty to follow the course of the Coppermine River, tracking it northwards to chart its mouth and then the shores of the Arctic Sea.4 For this important mission he was accompanied by a small naval party: Surgeon and naturalist John Richardson; two young midshipmen, Robert Hood and George Back; and Ordinary Seaman John Hepburn. In the Orkney Islands Franklin hired on experienced hands who were familiar with overland travel in Prince Rupert’s Land. Other passengers on that Atlantic crossing included colonists on their way to Lord Selkirk’s settlement at Red River. Prince of Wales was accompanied on this and many of her yearly transits by another HBC ship, Eddystone.5 Franklin’s first trip to North America to mount a land-based Arctic surveying expedition nearly ended in disaster before the explorers had even disembarked at York Factory. On 7 August 1819 – while nearing the Hudson Strait in thick fog– icebergs and a line of sheer cliffs appeared dead ahead.

The ship slammed into the rocky bottom of Resolution Island. The rudder was jarred out of position.6 A torrent of frigid water began pouring through rents in the stern. As the after hold filled with water, the ship was in real danger of foundering. More collisions followed. The crew used a small boat to tow the ship away from further harm. At the same time Franklin’s men and the ship’s carpenters worked to cut away damaged stern timbers and jury-rig repairs. Prince of Wales survived a 36-hour ordeal with everyone taking turns at the pumps. Finally arriving at the HBC Factory on the 30th of August, the exhausted expedition group must have felt relief at putting the Prince of Wales far behind them. Unfortunately, greater challenges lay ahead. During the Coppermine Expedition (1819-1822) the whole party nearly starved to death, with several members succumbing. The promising young officer and artist Robert Hood was murdered.

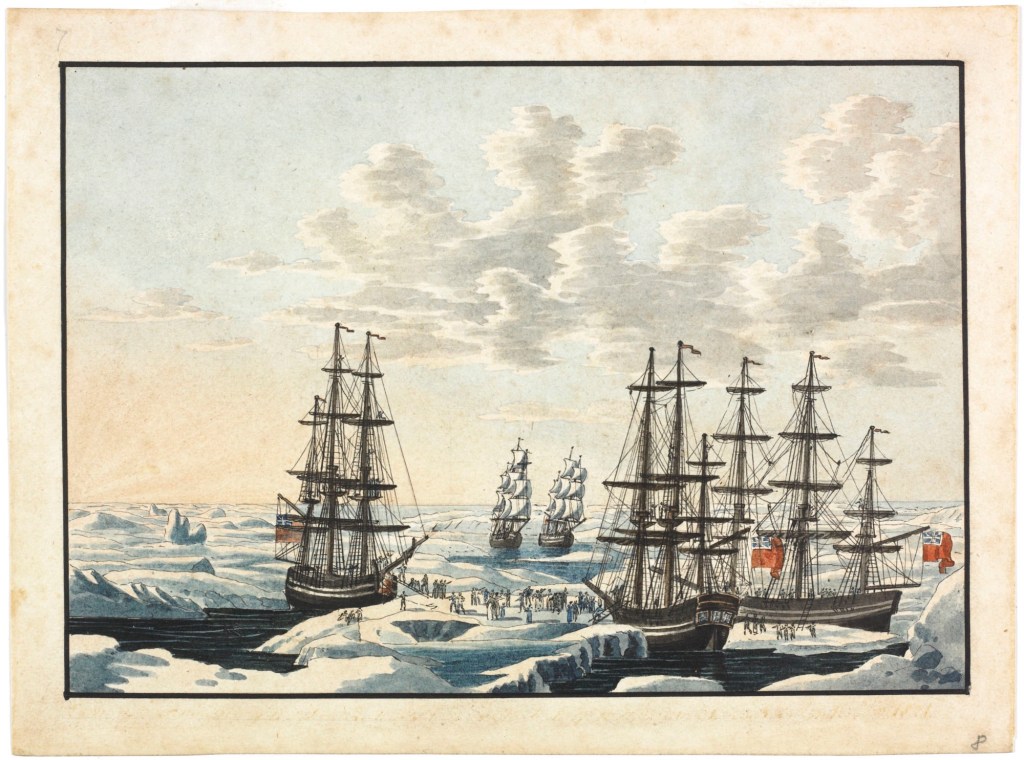

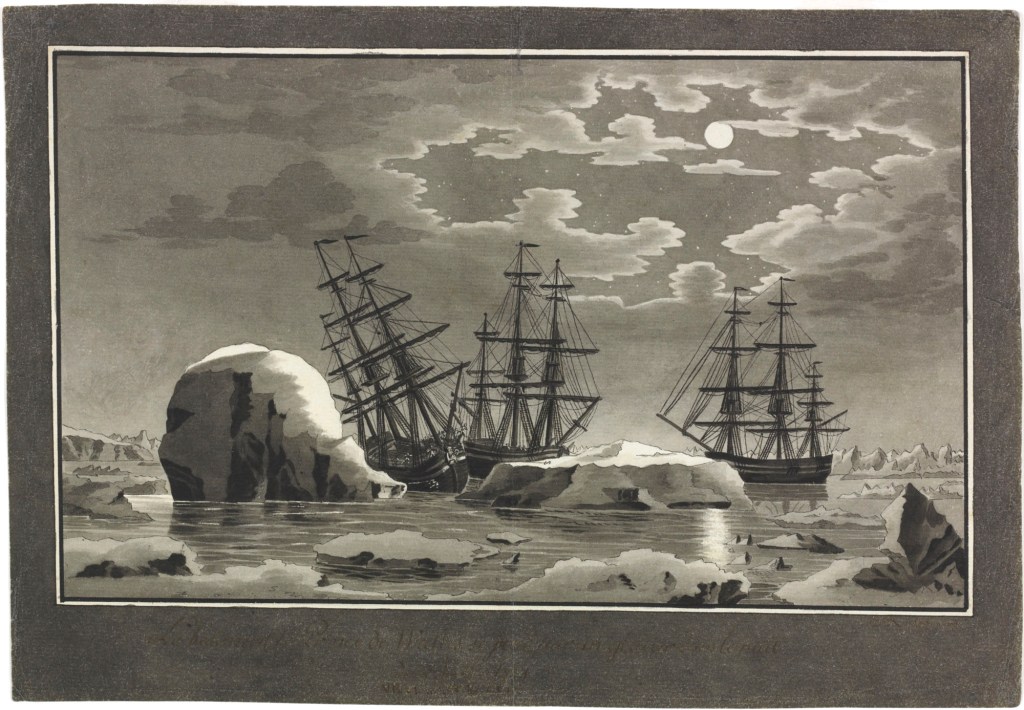

Meanwhile, Prince of Wales kept to the annual schedule of grueling voyages to and from Hudson’s Bay. During the 1821 season, a young Dutch colonist also emigrating to the Red River settlement, Peter Rindisbacher, was aboard Lord Wellington, sailing in company with Prince of Wales and Eddystone. He produced an artistic record of several notable events.7 On 16 July 1821, the HBC squadron unexpectedly met the other major contemporary Royal Navy project to explore the Arctic: William Edward Parry’s maritime expedition, in search of a Northwest Passage. Parry’s second expedition was headed west along the top of Hudson’s Bay to explore the Frozen Straits and Repulse Bay for a (not existing) passage westwards.8 Parry’s crews in HM Ships Hecla and Fury were delighted that the “Strange Sails” to the northeast had resolved themselves into three Company ships.9

Days later, Rindisbacher witnessed Prince of Wales again being mauled by an iceberg. After the entire starboard side was crushed, only a shifting of cargo to Eddystone and a jury-rigged sail stretched over the hull saved the ship.10 Lloyd’s (of London) survey reports reveal that the ship was carefully set to rights after each new round of damage, and was fastidiously maintained during her HBC career. Despite this history of collisions and groundings, she was still assessed in “A1” or prime condition, fit for all commercial service throughout the late 1830s.11

As Prince of Wales continued the yearly voyages, Franklin, who had won acclaim mostly for his published account of surviving the Coppermine ordeal, returned to mount another land-based exploration of the Arctic shores. The Mackenzie River Expedition (1825-27) saw Franklin add much to the evolving cartography of the Arctic, all without any of the drama and tragedy of his earlier journey. Another notable event that would connect Prince of Wales to the Franklin saga occurred in 1833, when a young Orcadian doctor, recently qualified in Edinburgh, signed on to serve as ship’s surgeon. Dr. John Rae journeyed far away from the Orkneys; he would not see his home of Clestrain for many years. Rae and Frankin’s friend and exploration companion, John Richardson, would complete remarkable overland surveying journeys together, before pairing up to look for Franklin’s missing 1845 expedition. Rae would eventually bring back the first accurate intelligence about the tragic outcome of the expedition, which was obtained from interviewing Inuit near Pelly’s Bay and trading for actual artifacts.12

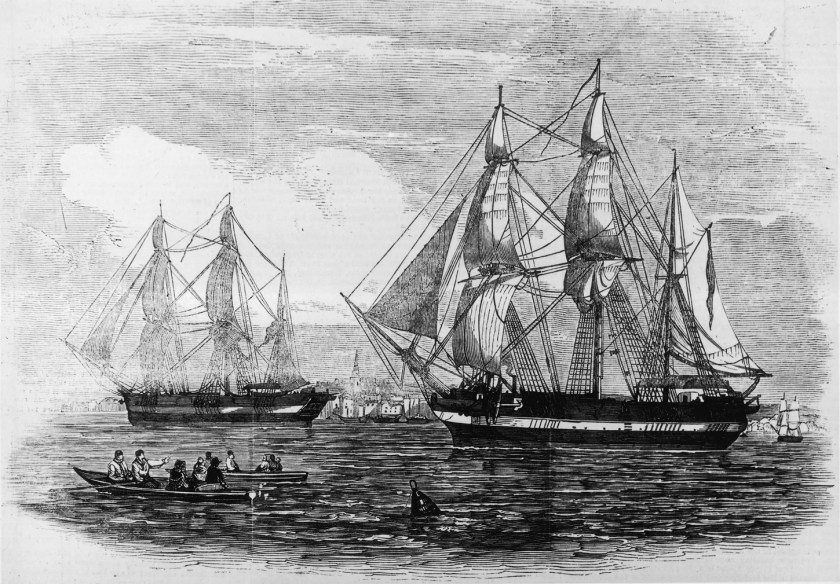

The Company eventually sold Prince of Wales in 1844.13 Instead of going to a ship-breaker’s yard, this redoubtable Arctic veteran was modified for a second career as a whaling vessel. the surveyors’ descriptions of the ship’s strengthened timbers and double-sheathed hull, found in the Lloyd’s reports, show that she was ideal for conversion. The refitted vessel sailed out of the busy whaling port of Hull under the command of Captain Dannet. During July, 1845, Prince of Wales was in the same general area as the whaling ship Enterprise (Captain Robert Martin, from Dundee), when HM Ships Erebus and Terror – virtually identical to William Parry’s ships of 1821, and on yet another Royal Navy Discovery Service Northwest Passage expedition – were sighted.14 Sir John Franklin’s two ships were tethered to an iceberg, waiting for favourable conditions to push westwards via Lancaster Sound.

The ships were riding incredibly low in the water, packed to the gunwales with supplies. Even the ice channels outboard of their hulls were encumbered with spare spars, and the ships’ boats amidships had been filled with some of the patent fuel for the engines!15

The Franklin expedition ships, HMS Erebus and Terror, setting out in late May 1845 from Greenhithe. This was originally published for the 24 May 1845 edition of the Illustrated London News. (Via wikimedia commons) These two reinforced ships were also not that different from Prince of Wales.

Members of Franklin’s crew took the opportunity to visit Prince of Wales. They were in a jubilant mood.16 The crews hoped to repeat the incredible progress Parry’s ships had made on his first voyage to the Canadian Arctic. Franklin, visiting with Martin onboard Enterprise, boasted to the whalers about the wonderful provisioning of his vessels: If they didn’t succeed at pushing through the Northwest Passage this season, the supplies would enable them to overwinter for a period of years. His crews had already been out shooting birds in the boats and would be salting them to supplement the stocks of meat. The whaling crews wished them well. At the end of July, the crew of Prince of Wales caught a last distant sight of Erebus and Terror.17 Franklin, his 128 men, and two stout ships disappeared into history.

As events would show, these three remarkable ships were sailing along on a similar trajectory towards shipwreck. Throughout the nineteenth century there was a yearly total of whaling ships that did not return to their ports. In June 1849 – after an incredible 55-year career – Prince of Wales was added to the list of marine casualties. She was crushed by ice, sinking in the familiar waters of the Davis Strait. The crew escaped by boat to the Orkneys. At this time, we still do not know exactly when Erebus and Terror sank, but all three ships may well have foundered during that same year. Prince of Wales was no Navy ship, but she had battled years longer than the Franklin ships in this same perilous environment of ice, rock, wind and weather.

If you have more information to help us add to the story about Prince of Wales’ fascinating service, leave a comment!

NOTES:

- John Franklin, as a young lieutenant, had already been on one Arctic exploration mission: An 1818 attempt on the North Pole in HMS Trent, under Captain David Buchan in HMS Dorothea. This expedition went up from Spitsbergen, but had to turn around well short of the higher latitudes. The first passage of this post is derived from the lyrics of “Lady Franklin’s Lament.” ↩︎

- For the early part of Prince of Wales career, there was an intense rivalry between the Hudson’s Bay Company and the Montreal-based North West Company, that sometimes deteriorated to open warfare. Relations between company employees reached yet another low ebb immediately before Franklin arrived in North America to set out on his Coppermine Expedition. This threw his provisioning plans into chaos, which contributed to the trail of starvation and suffering Franklin’s party travelled in the northern wilderness. The Colonial government forcibly merged the two companies in 1821, with the HBC name continuing on. For more information see Jennifer Brown’s article on the North West Company in the Canadian Encyclopedia. The HBC went into receivership early in 2025 and all stores had closed by 1 June, with certain intellectual property rights being purchased by Canadian Tire. Though the chain of stylish department stores resembled very little of the early days of a fur trading business and then empire, HBC’s absence from Canadian society is notable. As of August 2025, discussions are currently underway to sell the original 1670 Royal Charter. ↩︎

- For a brief account of the establishment of the HBC and the fur trading system across Prince Rupert’s Land, including the relationships and business between indigenous hunters, Métis trappers, and the various trading representatives of the Company and the HBC’s complex relationship to British colonialist policies, please see Melissa Gismondi “The untold story of the Hudson’s Bay Company” Canadian Geographic May 2020 (updated 2024). https://canadiangeographic.ca/articles/the-untold-story-of-the-hudsons-bay-company/ ↩︎

- The end of the Napoleonic Wars had left many Royal Navy officers on half-pay, as the fleet was placed into reserve and crews were dismissed. Franklin was fortunate to find continued employment in the Discovery Service. ↩︎

- Eddystone also had a notable history. She was originally completed at Hull in 1802 to serve a similar role to Prince of Wales, but for the competition: the North West Company. She was captured by the French, and then recaptured, and sold to the HBC. After her own eventful career, she was wrecked on the coast of Newfoundland exactly two years before Franklin departed on the last Expedition: 19 May 1843. ↩︎

- This description of Prince of Wales‘ dangerous 1819 arrival in North America draws from Ken McGoogan’s Searching for Franklin: New Answers to the Great Arctic Mystery (Douglas & McIntyre: 2023) pp. 85-89. ↩︎

- William Benoit “Journey to Red River 1821—Peter Rindisbacher” https://thediscoverblog.com/2016/05/02/journey-to-red-river-1821-peter-rindisbacher/ (2016-05-02). Peter Rindisbacher was 15 years old when he emigrated from the Netherlands to Lord Selkirk’s settlement at the Red River. He produced an incredible visual record of the travels and challenges of reaching the Canadian West. ↩︎

- One objective of Parry’s first two expeditions was to try to link up with Franklin’s continuing Coppermine Expedition far to the west. ↩︎

- Extracts of the ships logs and a brief description of the encounter can be found at ARCdoc: https://arcdoc.wordpress.com/2012/04/26/a-strange-sail-in-the-ne-quarter/ ↩︎

- “Lord Wellington (1811 ship)” entry in Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lord_Wellington_(1811_ship) ↩︎

- Lloyd’s (of London) annual survey reports for the HBC ship Prince of Wales are digitized and available at https://hec.lrfoundation.org.uk/archive-library/ships/prince-of-wales-1793/search/ship-name:prince-of-wales/page/1 ↩︎

- On Rae’s first journey, after leaving Moose Factory, Prince of Wales became frozen in, and could not make the yearly return trip to Europe. Rae worked to keep the crew healthy and free of scurvy, and apparently found some enjoyment from his Hudson’s Bay besetment experience! He stayed on in North America, following up on Franklin’s overland expeditions by surveying expanses of the North and the Arctic coastline for the Company. He completed incredible journeys which saw him succeed by using what he had learned from indigenous communities about travelling lightly and living off the land. He paired up with Dr. John Richardson, now an experienced Arctic surveyor, having served again with Franklin. The two continued the inland surveying of the north, even as they searched for information about what happened to Sir John Franklin and his 128 crew. Rae’s fourth expedition along the Arctic shores would bring back the first intelligence of the complete destruction of the Expedition, gleaned from Inuit who had acquired relics from others who had seen the dead men, boats, tents, and even evidence of cannibalism. For a brief biography, see C.S. Houston “Arctic Profiles: Dr. John Rae” Arctic 40(1) (March 1987) 78-79. https://pubs.aina.ucalgary.ca/arctic/Arctic40-1-78.pdf ↩︎

- Prince of Wales appears to have been replaced in Company service in 1841 by two newer sisterships: Prince Albert and Prince Rupert. ↩︎

- Jones, A. G. E. (1969). Captain Robert Martin: A Peterhead whaling master in the nineteenth century. Scottish Geographical Magazine, 85(3), 196–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/00369226908736133 ↩︎

- Edward Couch to parents 4-11 July 1845 quoted in Potter, Koellner, Carney, Williamson (Eds.) May we be Spared to Meet on Earth – Letters of the Lost Franklin Arctic Expedition (McGill – Queen’s University Press, 2022) 241. ↩︎

- Fitzjames quoted in Paul Watson. Ice Ghosts: The Epic Hunt for the Lost Franklin Expedition (McClelland & Stewart: 2017) P43. The specific section about James Fitzjames and six hands boarding Prince of Wales has no direct citation. ↩︎

- Traill, H.D. – The Life of Sir John Franklin, RN. John Murray (1896) as quoted by Alison Freebairn “Searching for Henry Foster Collings (posted 2023-09-10) https://finger-post.blog/2023/09/10/searching-for-henry-foster-collins/ ↩︎

Fascinating stuff. Well presented. Robin Hood was on board one of them. Who knew? I had to lookup bergy bits, growlers and Orcadian. And why did they have an engine on board?

Robert Mayne