A year ago we “floated” the idea of raising an important artifact of the lost 1845 Sir John Franklin Expedition, from one of the two incredible shipwrecks at the Wrecks of HMS Erebus and HMS Terror National Historic Site: A ship’s boat from HMS Terror. In the intervening months, we have bulked-up on our boat-raising research, and have circled back to this topic. We’re doubling down: the World NEEDS the Terror boat back on dry land.

During September 2024, Parks Canada underwater archaeologists were again on site in Nunavut, in the high Canadian Arctic. They were conducting an archaeological program at the extraordinary shipwrecks of HM Ships Erebus and Terror. Early indications suggest that they had a long dive season! We are very much anticipating the release of information about newly-recovered artifacts and other discoveries.

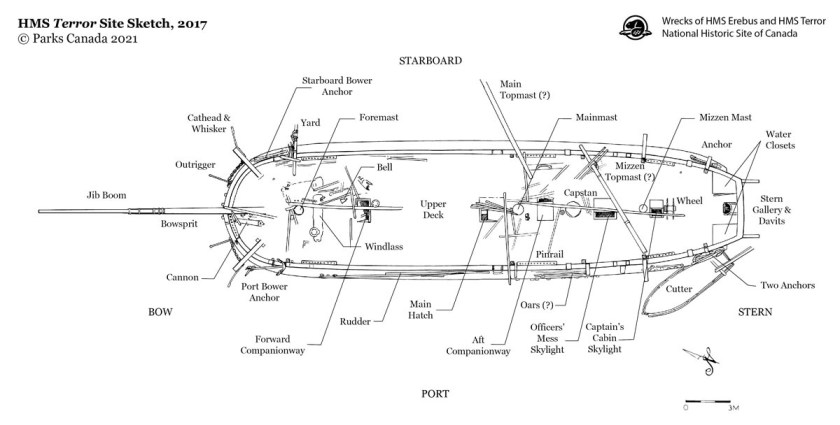

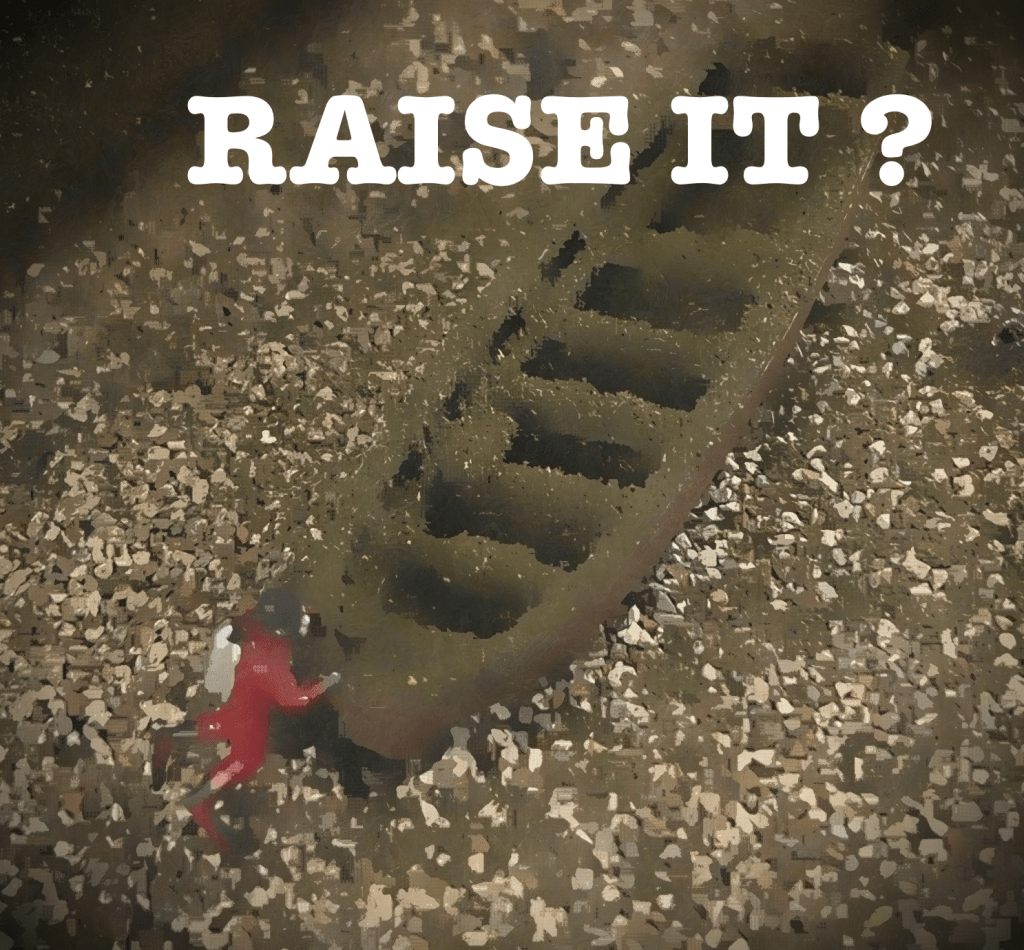

There is an artifact that we hope someday will be recovered: one substantially intact 23-foot/7m ship’s cutter. The boat was pulled down as Terror sank in a bay along the southwestern coast of King William Island later named, by coincidence, Terror Bay. Lost about 175 years ago, it has, like the rest of the Terror site, remained astonishingly intact, 80’/14,4m beneath the freezing waters of the Bay.

In the earlier post, we explored the idea that this important artifact could be raised from its location on the seabed off the port quarter of the Terror hull (the same caveats still apply).1 The boat wreck could then be conserved and stabilized for eventual public exhibition. Visitors would be able to engage with a remote National Historic Site of Canada by interacting with a substantial Franklin Expedition artifact. We also proposed that it could be replaced with a wooden replica, carefully deposited in position back at Terror Bay. This replica boat would replace the original at the wreck site: It would aesthetically preserve the integrity and character of the site; it could also help monitor changes to the seabed environment that may be less apparent on the original wreck structures; and it could provide powerful commemorative options for an in situ memorial, that would remain, marking this important site for generations to come. Why not have a memorial boat serve as a submerged cenotaph, with plaques in three languages – English, French, Inuktitut– to commemorate the lost 129 men of both the Erebus and the Terror?

This sunken cutter is the only boat from either ship that has survived the destruction of the Expedition in any semblance of its original condition. It would be a signature object around which to build commemorative and interpretive programs. After treatment, it could be placed on display at the Nattilik Heritage Centre in Gjoa Haven, or another suitable museum.

There was an era in underwater archaeology when raising a wooden artifact that had been immersed for any length of time was a recipe for destroying it. Sunken wood becomes saturated with water molecules, and swells. This alters the original properties of the wooden structures. After it is exposed to air and dries out, the artifacts become fragile to the point of crumbling. During the 1960s, starting with the famous archaeological work on the Vasa warship wreck in Stockholm Harbour, conservators learned to treat wood and metal artifacts with Polyethylene Glycol (PEG). This compound can replace the water content in the wood, to help it retain its basic dimensions and structure, and allow it to be stabilized for long-term preservation.

The success of a project of this importance would depend on securing an elite team of archaeologists and conservators. The good news is we did not have to look far afield! The archaeologists currently working on the wrecks – Parks Canada’s Underwater Archaeology Team (UAT) – have some of the most relevant expertise in the World at successfully completing exactly this type of project. They have surveyed, disassembled, conserved, and reassembled sunken boats from National Historic Sites of Canada – and they’ve done an incredible job. During the late 1960s Parks Canada was an early adopter of PEG treatment to help conserve raised boat wrecks.2 Since then, they have tackled larger and more complex projects.

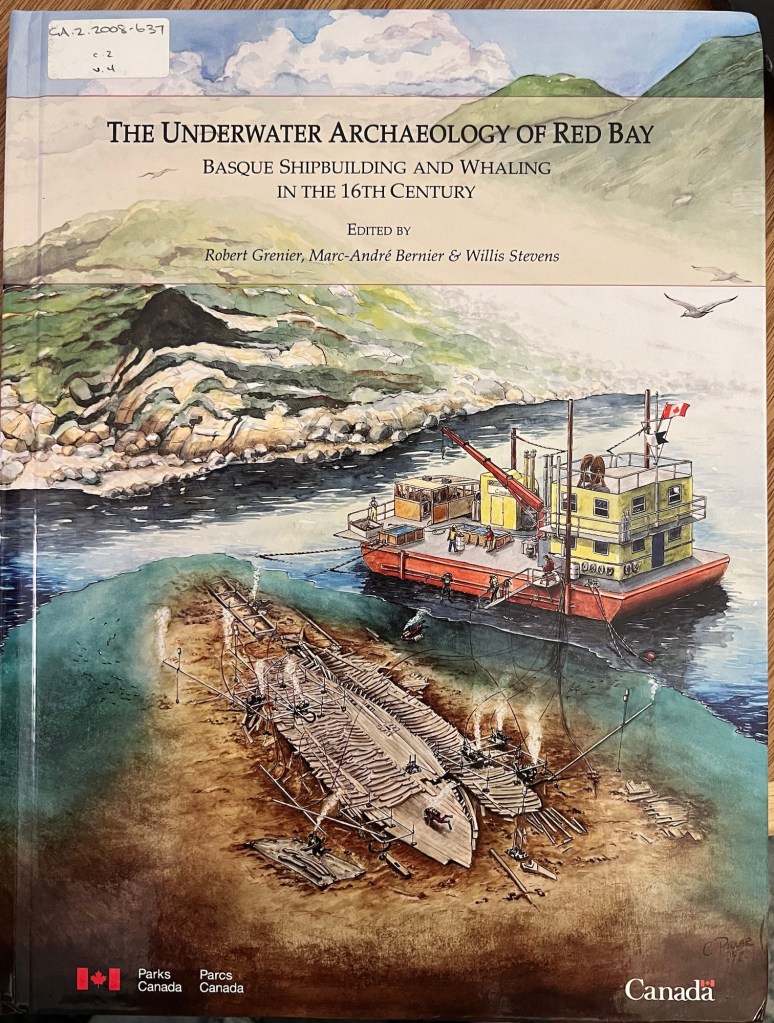

At the Red Bay National Historic Site, Labrador, the remains of a 90-foot long, 250-300 ton Basque whaling ship, usually identified as the San Juan, were methodically excavated from 1977-1992. A thrilling discovery was made in 1983 under the timbers at the stern of the 16th Century shipwreck: The remains of a well-preserved chalupa-type whaling boat. The whaling boat is believed to have been dragged under at the moment of the shipwreck, in a similar manner to Terror’s cutter. The project was extensively described in a multi-volume publication by Parks Canada.3 It was a remarkable find – a missing link in the development of whaling boats and a Basque precursor of North American-built settler and indigenous whaling boats. After meticulous planning and preparations, the decision was taken to raise the remains of the four-hundred year old vessel to reassemble it. An article by Charles Moore, a leading Parks Canada archaeologist, and a piece on the Parks’ website – “Archaeology of a Sixteenth-Century Basque Whaling Boat” – describe this work.4

The recovered timbers were shipped to Ottawa, stabilized and treated with PEG, and then painstakingly reformed and reassembled in Parks’ conservation facilities. In July 1998, after a nerve-wracking drive back to Labrador, the 26-foot boat was placed on display in a new interpretation centre back in the community of Red Bay. Today, the artifact continues to offer visitors an accessible connection to the history of Basque whaling in North America, and the National Historic Site under the adjacent waters of Red Bay. A chapter of Parks Canada’s multi-tome series on the Archeological program and discoveries of Red Bay, written by archaeologists Ryan Harris and Brad Loewen, documents the UAT’s meticulous efforts to survey, excavate, raise, and reconstruct this boat.

It was especially challenging to extricate this boat from the whaling ship remains: the chalupa had been crushed by the bulk of the San Juan’s stern and flattened later by collapsing ship timbers. It was also sandwiched between articulated wreck elements. Terror’s cutter, by contrast, appears to be substantially intact and disassociated from the main site. Indeed, from the above site plan, and Parks Canada photos and film, it appears to be sitting pretty, filled with protective sediment and lightly embedded in the muck. What worked for the Red Bay site during the 1990s can now work for Terror Bay in our years. Raising the boat could be the type of tantalizing project that would sustain popular enthusiasm for the meticulous archaeological investigation of both sites over the coming decades.

The preserved artifacts mentioned in the text and notes of this post have all become prestige objects to build museums, visitor centres, and collections around. This is what we would wish for the Wrecks of HMS Erebus and HMS Terror National Historic Sites of Canada. It does feel like it is time we start talking about raising the Terror’s boat.

Rise again, rise again, that her name not be lost

To the knowledge of men. We’ll make the Terror ship’s boat rise again! [paraphrase of Stan Rogers’ The Mary Ellen Carter]

We asked a year ago and are asking again: Have we convinced you? Let us know in a comment!

REFERENCES