A hundred-and-seventy-one-years ago, crew members of the supply ship Breadalbane gazed forwards from the bow rails, looking towards the forbidding cliffs and unknown shores of Beechey Island, in the High Arctic. Today, the spot where they once stood is preserved 310 feet/ 95m underwater, near those same cliffs. Breadalbane’s shipwreck endures as a magnificent time capsule of a remarkable era of Arctic exploration.

This fourth post will focus on the program of archaeological research conducted ten years ago by Parks Canada and the Canadian Armed Forces at Beechey Island, Nunavut. We will also provide a brief description of the wreck, accompanied with remarkable images. The first post summarized the loss of this supply ship in the High Arctic in August 1853, while provisioning search expeditions looking for the Franklin Expedition. The second post described the original 1980s discovery and exploration of the wreck. The third post showcased the construction of an archaeologically-based scale diorama of this National Historic Site of Canada.

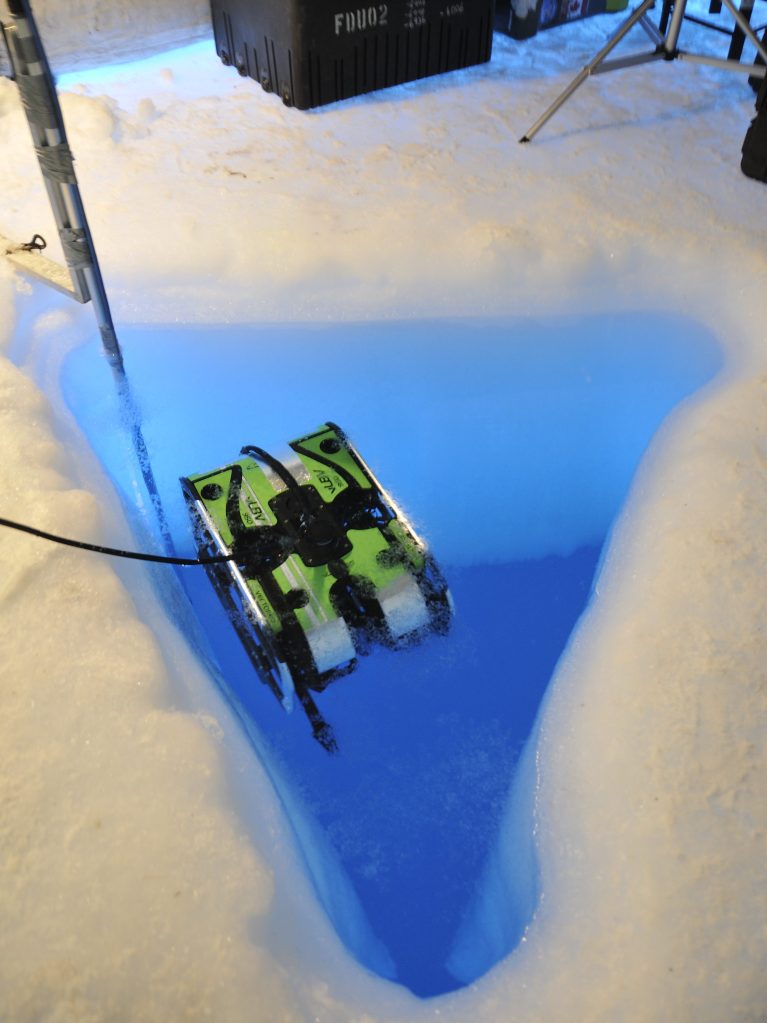

Two decades after the last visits to Breadalbane, there was a revived interest in exploring the wreck. The 2012 Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) work involved a preparatory survey by a naval dive team using a remotely operated vehicle (ROV). Parks Canada archaeological participation would correspond with the 2014 iteration of Operation NUNALIVUT, a CAF exercise in the Arctic.

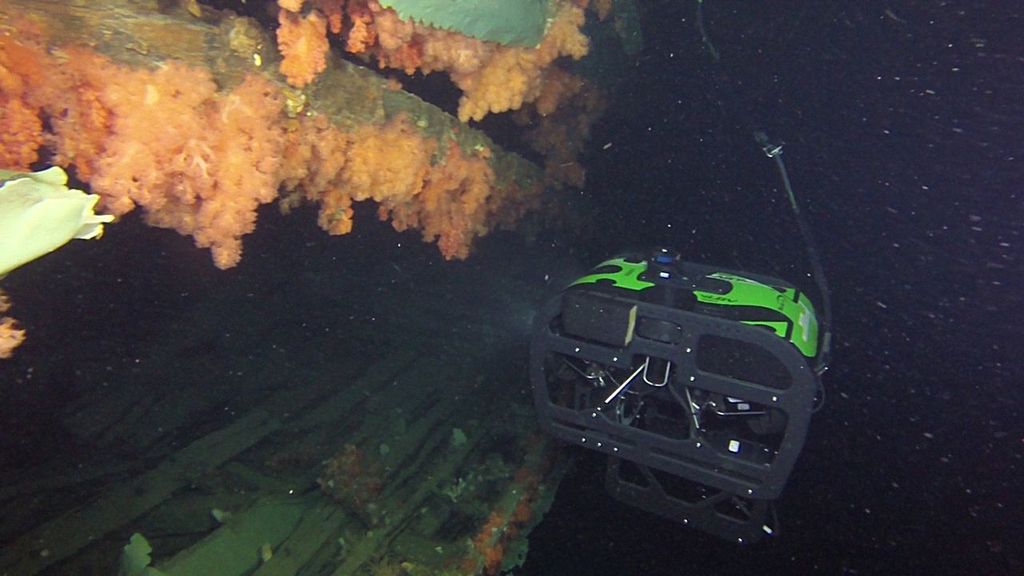

This visit involved surveying and filming efforts employing SeaBotix ROVs, one of which used multibeam sonar to guide the exploration to sites of interest, and to construct a detailed visual survey of the site. Parks Canada Underwater Archaeologist Jonathan Moore was the permit holder for the archaeological program, working from an ice camp 330’/100m above the seafloor.

We are very excited to share stunning ROV images from this visit. Some photos were generously provided to us by Parks Canada, and others are from the Department of National Defence. These allow us to navigate around and inside this wrecked supply barque to note some of her outstanding features.*

The return to Breadalbane was an exciting phase in the archaeological survey of Franklin Expedition-related sites, continuing on from the 2010-2011 Parks Canada-led location and dives on HMS Investigator at Mercy Bay, Northwest Territories, and coming a short time before the discovery of Sir John Franklin’s lost flagship, HMS Erebus, in September 2014. One objective of the underwater survey was to assess changes to the Breadalbane since the 1980s.

Though Breadalbane is often treated as a footnote in the saga of Arctic exploration, and as “also wrecked” in the high-drama surrounding the lost Franklin Expedition, it is an incredible site – many areas have not witnessed significant deterioration.

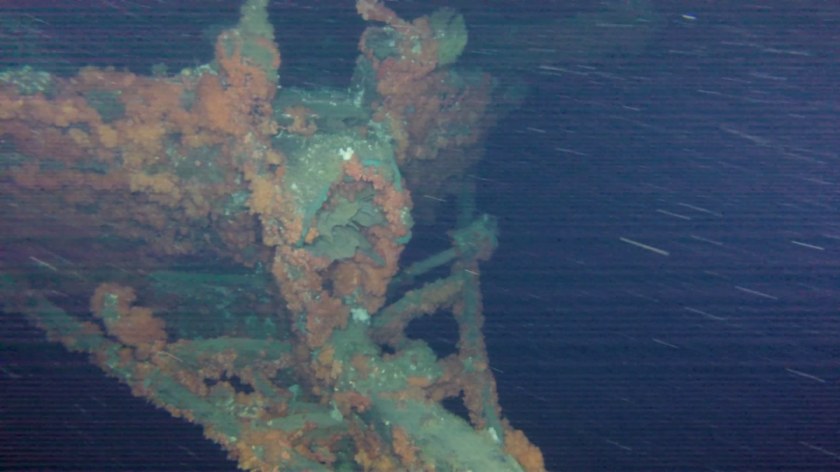

The marine life growing at the wreck site is as stunning as what Dr. Joe MacInnis and his teammates encountered in the early 1980s.

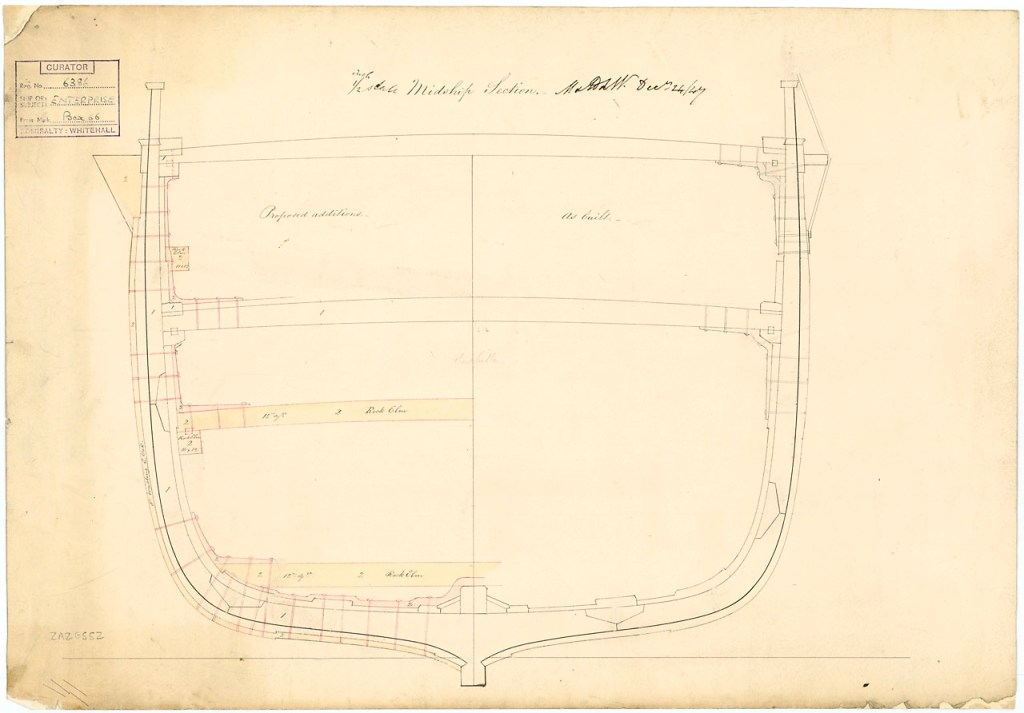

Breadalbane helps us understand the range of options available to the British Admiralty for reinforcing mid-19th Century vessels intended for polar service. This supply vessel was not a “paper ship”, totally unprepared for the rigors of Arctic service, but rather received hybrid modifications which were suitable to her intended role: “Continuation service” outbound for the Lancaster Sound.1

Breadalbane was going north in the high summer. The ship was not intended to be beset by ice – frozen-in over the long, dark months. The commanding officer of HMS Phoenix, Captain Edward Augustus Inglefield, was under specific instructions to unload Breadalbane’s vital cargo at Beechey, and then get her turned around and on her way back south before the season changed and all the navigable waters froze.

An 1853 Lloyd’s special survey report notes that the outside of the bows was shielded by 4″ thick Canadian elm planks, which extended 7′ / 2.1m below the water, from the stem back to a point even with the foremast. This was a lighter-duty version of the combined sheathing and iron-plates installed at the bows of the Franklin search ships.

Ultimately, these reinforcements did not save the ship from being crushed. The unexpected movement of the ice south of Beechey Island on 21 August, 1853 was instantly fatal to the fabric of the lower hull. The ice created a large rent that stretches for 70’/ 21m along the starboard side, revealing the ship’s mostly empty cargo hold.

I would like to acknowledge the significant assistance of Parks Canada’s Underwater Archaeology Team, and especially Jonathan Moore, who generously shared Parks’ substantial research and the above images.

- This is how the Captain of HMS North Star, William J.S. Pullen, described Breadalbane in a letter to John Barrow, written at Beechey Island soon after the sinking. At this time North Star was frozen-in on the inland side of Beechey. As noted in the first blog, the Lloyd’s survey report of early 1853 is an important source for interpreting the modifications Breadalbane received for her “Continuation Service” (a termed used in their survey) in early 1853. ↩︎