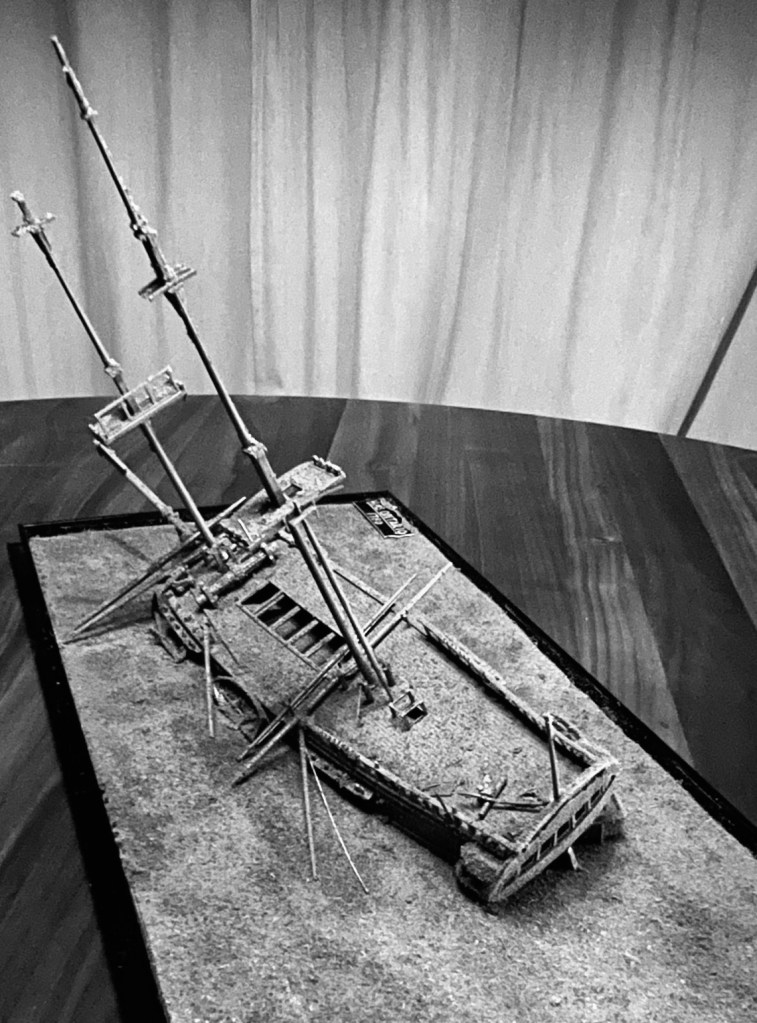

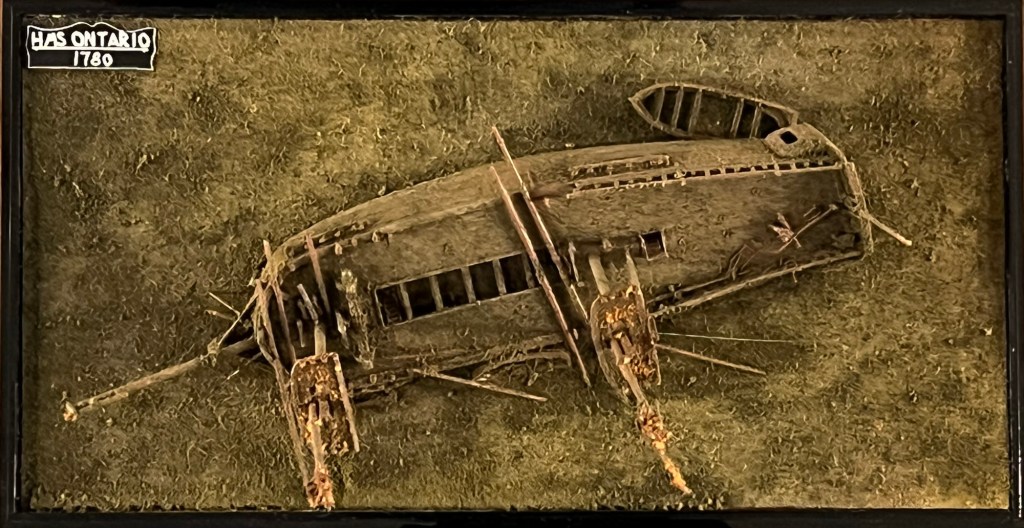

There is an incredible ship, frozen in time down in the depths of Lake Ontario. HMS Ontario was a wooden warship that sank in a storm October 31st, 1780. This tragedy claimed the lives of as many as 129 sailors, soldiers, Indigenous warriors, American prisoners, women and children. All these decades later she is still down there, astonishingly intact. This ghostly Revolutionary War relic appears almost as if she is sailing west across the lakebed. After months of work, we have completed a model diorama to help interpret the history of this archaeological marvel.1

Early in 1779, with the American Revolutionary War raging along the Lower Great Lakes watershed, Master Shipwright Jonathan Coleman designed a British warship for service on Lake Ontario. He drafted out a scaled-down version of his Royal George, already active on Lake Champlain.

This new vessel, to be named Ontario, had a pleasing sheer, a full underbody, and elegant decoration at the stern.2 The bows were adorned with a simple scroll. This impressive inland warship was built at Carleton Island (the dockyard facilities of the British on Lake Ontario near present-day Kingston). She was launched 10 May 1780, and when completed that summer, her twenty-two cannon made her the most powerful warship operating on the Lake.

© Crown copyright. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

The gundeck was 80’/24.4m long, the ship displaced about 220 tons and the two masts were set up as a snow (similar to a brig-rig but with a small pole mast running from deck up to the level of the maintop, which normally carried a loose-footed gaff sail). She was a beamy 25’/7.6m wide, and had a capacious hold, appropriate to her main role of military transport. Her armament consisted of sixteen six-pounder cannon, mostly disposed on the gundeck, and lighter pieces on the quarterdeck and focs’l. Her hull was somewhat shallower than an ocean-going vessel of this length.

The careers of warships on the Great Lakes during the 18th and early 19th centuries were generally brief, as hulls were often hastily-constructed of green wood and wore-out quickly over the harsh winters. Even so, Ontario had a woefully short existence: a few months of ferrying troops and supplies. Under the command of Captain James Andrews, she supported the continuing “Burning of the Valleys” campaigns, helping to supply John Butler and Mohawk leader Thayendanegea (Joseph Brant)’s forces and other Indigenous allies fighting as part of the Haudenosaunee / Iroquois confederacy. On 26 October 1780, she departed Niagara bound for either Oswego or Carleton Island. Lt. Colonel Mason Bolton, Commanding Officer of the 8th King’s Regiment at Fort Niagara, was taking passage to England to convalesce. The crowded ship was sailing along the southern shore of the Lake.

A violent storm swept from northeast to southwest across the Lake on 31 October. The crew were likely caught by surprise late at night, as a sudden squall overcame the ship in the darkness and laid her over on to her beam ends. Andrews, Bolton, and more than a hundred other unfortunates disappeared into the Lake.3 The next day, debris was found near Golden Hill by a party of Butler’s Rangers and others who were returning to Niagara from Oswego. Boats, hatch coamings, sails, hats (including Andrews’ own tricorn), the binnacle cabinet, and some sections of quarter lights (windows) had washed up. Much later, in July 1781, a macabre reminder of the loss surfaced–six bodies floated ashore. These victims had been trapped at some intermediate depth until the lake waters released them. No other discoveries would provide context to the loss. The War and life in the (warring) colonies moved on. Ontario’s place in the squadron was taken by a new sistership, Limnade, and the story faded from memory.

Historians of the frontier campaigns of 1780, maritime scholars, and history buffs did not forget about Ontario. Of the many ships that have come to grief in the Lake, her story remained unique. When new technologies were developed that allowed amateur shipwreck hunters to search in deeper areas (which had been the preserve of well-funded professional expeditions employing incredibly expensive specialist equipment), enthusiastic searchers set out on the Lake to find the resting place. There were several claims over the years announcing that Ontario had been located, and many other lost ships were discovered.

Jim Kennard, of Fairport, NY, had an interest in Ontario that stretched back to the 1970s. After retirement, he returned to searching and built his own sonar outfit. He partnered up with Dan Scoville, a recreational diver from Rochester who had experience building ROVs (Remote Operated Vehicles). On 24 May 2008 – after three years of dedicated searching – a promising target appeared on side-scan sonar images onboard their search boat. In common with almost every discovery story we have ever heard, they were packing up and turning for home when the target appeared! The find was confirmed two weeks later by footage from Dan’s ROV. The rich documentary record revealed a shocking sight 500’/152m down: During the twenty-two decades the ship had awaited discovery, she had barely decayed!4

The ship is deeply embedded in lake sediment, with a pronounced list to port. The two masts still tower over the site. The mainmast is fully intact to its topgallant mast cap. It is unusual for a wooden wreck to be leaning so steeply to one side, and may speak to a fatal shifting of ballast or guns under the onslaught of the storm. The bowsprit and decorative scroll points west, back towards Fort Niagara.

A large ship’s boat rests just off the starboard quarter above the sediment. The loss of lights from quarter and stern galleries opens up tantalizing views of the interior of the great cabin. On deck the tiller bar leans over hard, continuing the angle of the rudder tucked under the counter. It is as if the ship went down while the crew tried desperately to steer the vessel to starboard. Two cannon carriages appear to be wedged underneath it. There is very little visible damage, and few missing elements. On the whole, it is difficult to credit that an 18th Century ship could have survived into the 21st Century in this condition. The Ontario site endures as a lovely wreck of a beautiful ship. We hope the diorama helps interpret this site, and that the Ontario resting place is protected from harm.

For more information about the model and the sources consulted, read more in the Dossier! (next page)

Continue reading “The Ontario Wreck Diorama – Yours to Discover!”