HMS Calypso was completed as a a steam-powered corvette – a uniquely Victorian mix of old and new technologies- in 1883. After a career of transformations, her hulk rests, all these years later, in a quiet cove in Newfoundland. She remains a historic artifact of Newfoundland’s important naval traditions. Years after adding a Google Earth view to my shipsearcher database, I recently got a chance to visit the site. Join me as I explore Calypso’s interesting past and current state!

In 1883, Robert Falcon Scott, a young midshipman serving in HMS Boadicea, sat down to sketch a picturesque seascape and a lovely ship: The newly-commissioned HMS Calypso. Boadicea, an older corvette, was sold to the scrappers at the turn of the 20th Century. Scott went on to legendary fame as a polar explorer, before perishing in Antarctica after attaining the South Pole in 1912. All these decades later, Calypso remains.

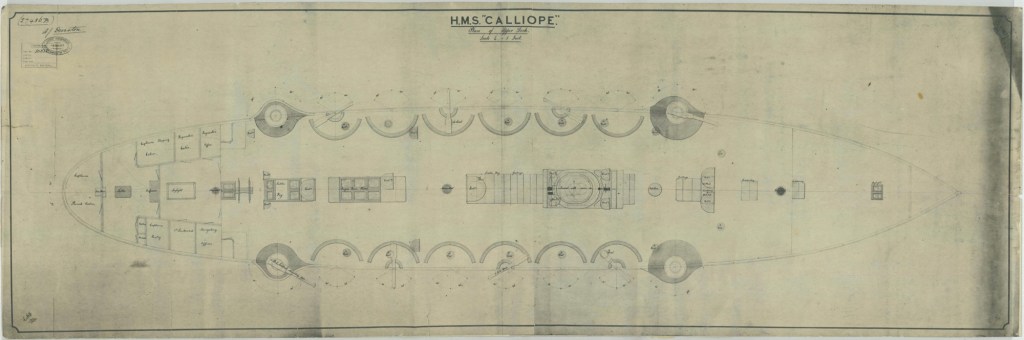

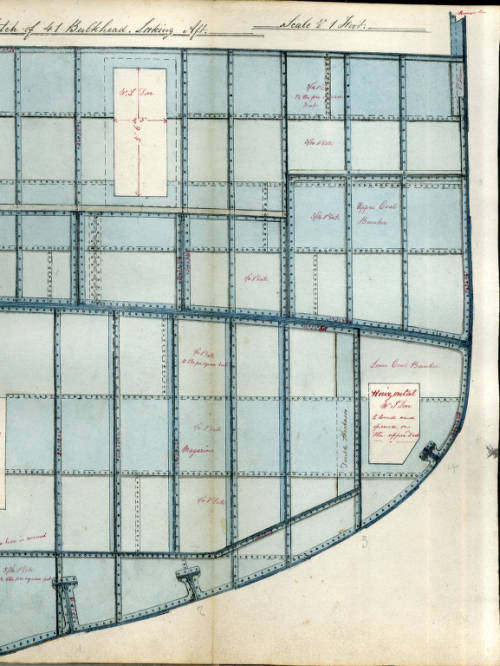

Sir Nathaniel Barnaby, Director of Naval Construction, had designed this and several predecessor classes of corvettes, and sisterships Calypso and Calliope were both built at Chatham Royal Dockyards. Where earlier corvettes were built of a mix of iron frames and wood planking, the Calypso class had a steel hull, with wooden sheathing, and a copper-clad underbody. The modern steel hull was structural and complete, but the wood (mahogany planking above water) aesthetically linked the ships to the rest of the sail-and-steam navy. More wood below the waterline created a barrier between the steel and the same sheets of copper alloy that the Royal Navy had used to protect its ships from wood-boring marine life and biofouling since the mid-eighteenth Century.1

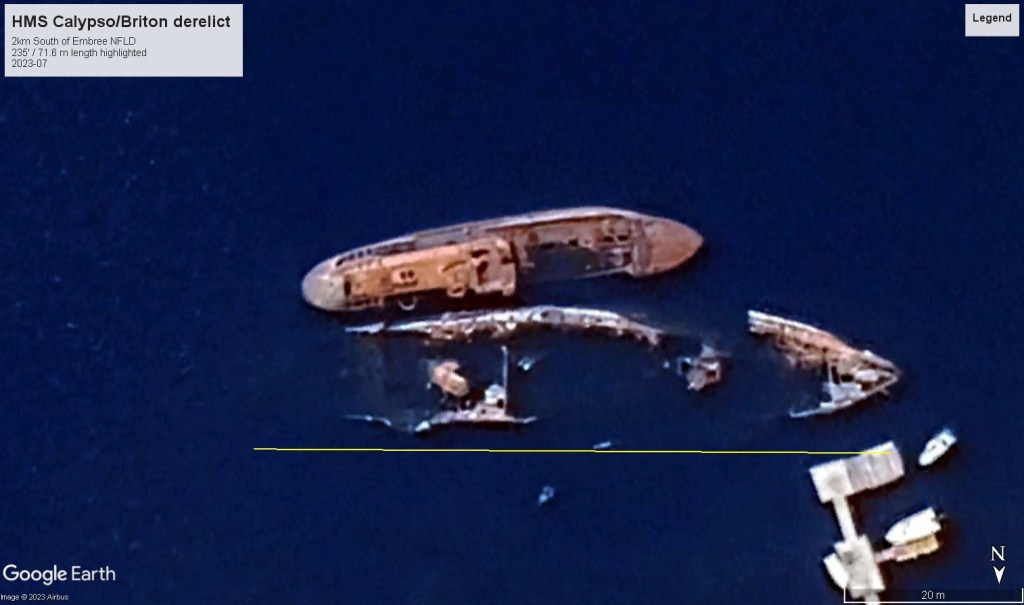

The ship had vestigial features from the Victorian sailing navy: A towering three-masted sailing rig, a broadside layout of cannon, and elaborate stern galleries (which were merely decorative cladding).2 Contemporary photographs show that the Calypso had a spectacular appearance with all sails set, and, when running before the wind, studdingsails could extend the canvas outwards like wings. Improving on the Barnaby’s earlier Comus class, they were slightly longer, at 235’/71.6 m between perpendiculars, and heavier, at 2,700 tons. They were substantially more powerful, with larger engines that could propel the single screw with over 4,000 units of installed horsepower.3

The class was armed with modern 6” breech-loading rifled guns.4 These were mounted in four sponsons (structures that mount armament which project out from the hull), with a wide field of fire. Five gunports were sited along the upper deck between the sponsons. A 5″ gun was mounted behind each port. Quicker firing light guns, Nordenfelts, were mounted high on the bulwarks, and were intended to protect from smaller, faster craft, such as torpedo boats. The two ships had a pair of 14″ diameter “carriage torpedoes.” These used compressed air to launch themselves out of cradles to start their run. Like the Comus class, the Calypsos had a partially-armoured deck of steel that protected some of the vital machinery – engines and boilers – low down in the hull just under the waterline.

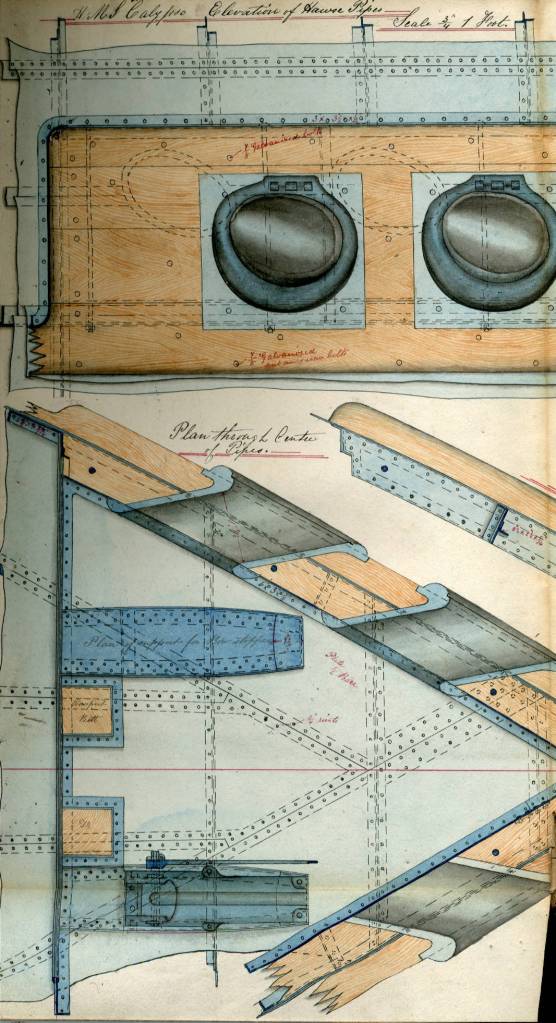

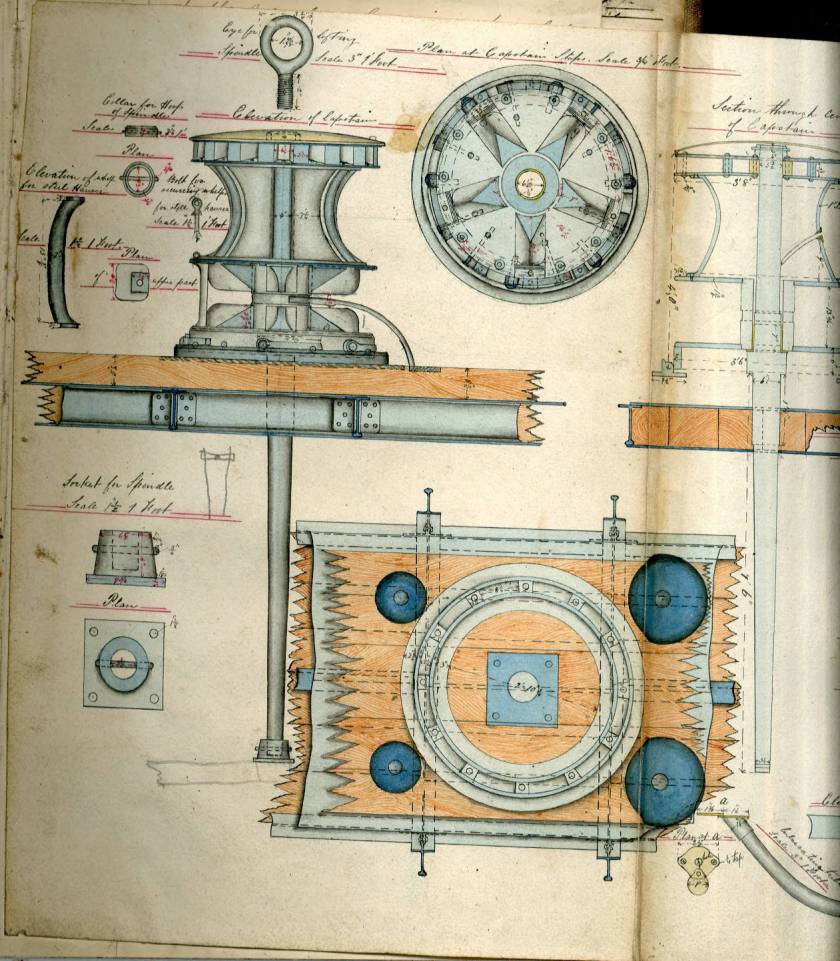

Predecessor Royal Naval classes had abandoned the graceful clipper stem for an upright bow with a massive bronze ram installed underwater. These were the last Royal Navy corvettes with a full sailing rig. Gaping deck ventilators and a wide buff-coloured funnel broke up the run of the upper deck. The ships were designed to be economical for long-distance cruising about the far-flung British Empire, and could sail and steam between widely-dispersed coaling stations. A contemporary folio of design blueprints, today in the archival collection of the Maritime History Archive, Memorial University, Newfoundland and Labrador, helps us reconstruct some of these technical design features (look out for these structures in our photos of what remains of Calypso elsewhere in this post)5:

Unfortunately, from the day they were designed, the idea of a sailing-steaming corvette cruising the world’s oceans was on borrowed time: A new generation of cruisers, the Leander class were being designed, and the Admiralty quickly halted plans to build more corvettes.6 The Leanders were larger, heavier, more powerful, and had more armour and more bunker capacity to steam to distant ports, or police merchant sea lanes. They improved upon the Iris class despatch vessels, and had a similarly cut-down barquentine rig.

Calypso’s Sistership HMS Calliope -completed in 1884- had an eventful career in the Far East, gaining fame for being the sole surviving warship from a terrible cyclone off Samoa in 1889. Calliope became a drill ship on the Tyne in 1907, and survived until dismantlement in 1951. Her name is perpetuated by the current shore establishment at Gateshead.

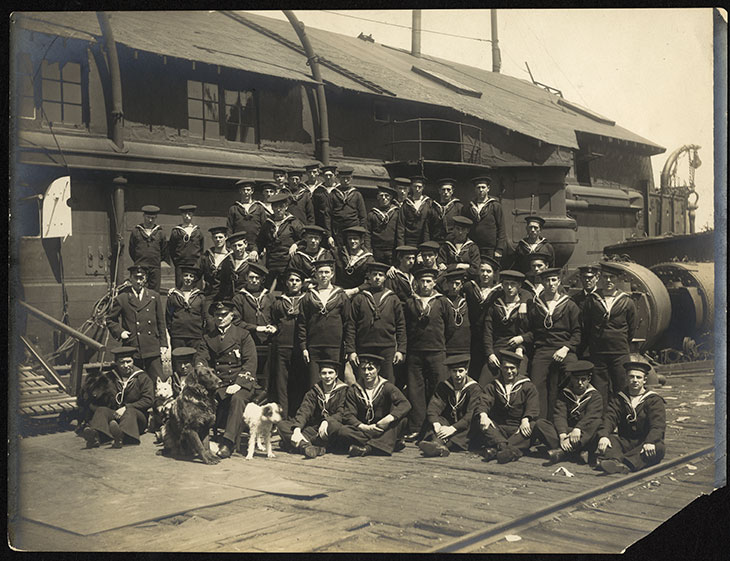

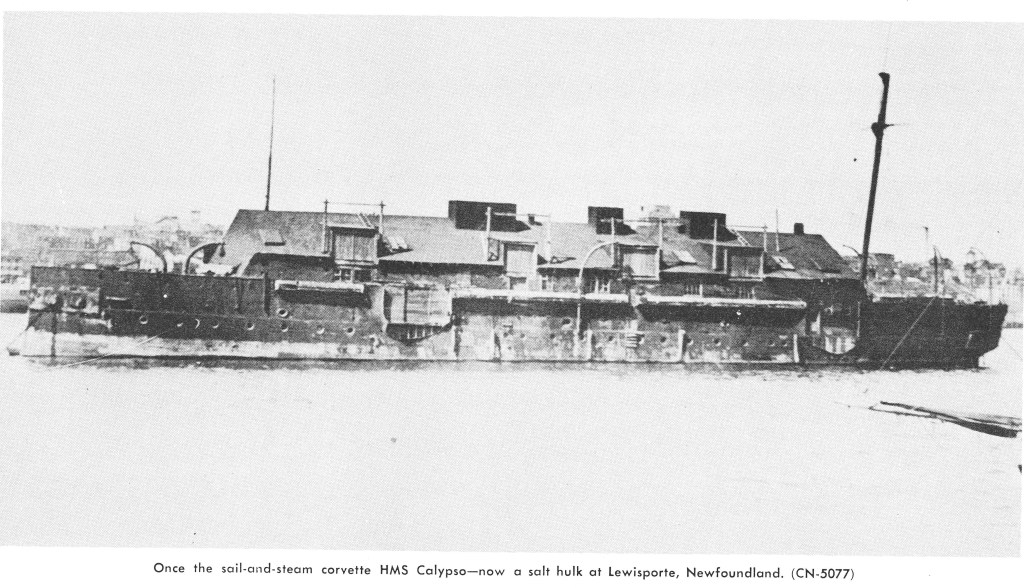

Calypso had a brief period of active service, cruising to distant ports as a member of the Sail Training Squadron. In 1895, Walter Hose, who would go on to serve as Director of the (Canadian) Naval Service during the Interwar era, was posted to Calypso. She was laid up at the end of the Nineteenth Century. In 1902, she was taken out of reserve and sent to Newfoundland to help train naval reservists in St. John’s for the newly-created Newfoundland Royal Naval Reserve. Newfoundland was the first colony where a naval reserve was formally established, and the Dominion was seen as a potential goldmine of seafaring experience, with many residents connected into seafaring traditions in the ports and outports of “the Rock.”7 Calyspo’s sailing and steaming days were over; the vessel was quickly converted to a depot ship, with deck houses built over the weather deck, funnels and machinery taken ashore, and most of the masts taken down.

During the First World War, the Calypso establishment trained many young Newfoundlanders for service with the Royal Navy. Almost 2,000 members served in everything from the massive battlewagons of the Grand Fleet, to armed trawlers, and 192 died.8 Alongside the Royal Newfoundland Regiment, the Forestry Corps, and merchant mariners, they represented the Dominion’s outsized-contribution to the Allied cause.

Calypso was renamed HMS Briton in 1916, to leave the name available for the new “C” Class cruiser. Eventually, Briton was sold off in 1922 to become a salt hulk in St. John’s. Moved to Lewisporte in 1952, most of the interior was stripped of valuable items. Some local residents hoped to save the moldering vessel for preservation. Instead, during 1968 the hulk was towed slightly north to near Embree, and set on fire.9

The derelict has slowly deteriorated there ever since.10 Today, she functions as a sort of jetty or breakwater, alongside an old fishing trawler. There is remarkable drone and video footage of the site from 2022 at “Discovering Newfoundland.”11 Take a look at the footage below to see the submerged portions:

On a recent trip to Newfoundland, I had a chance to visit Embree and swim around the remains. The hull has settled at a slight list to starboard. The bows are most recognizable, along with the some of the ship’s deck structures, which rise out of the muck. These tall boxy features originally housed a set of ventilators, connected by a louvered structure. As the above drone footage shows, the submerged stern section is recognizable, and, incredibly, Calypso still had the remains of the lower mizzen mast jutting upwards above the site in 2022!12 The capstan, about a third of the way aft from the bows, is one of the remaining distinctive naval artifacts.

Much of the starboard side, adjacent to a small pier, is collapsed and displaced outwards onto the bottom. A small portion rises where the wheel would have been, where a bulkhead still shows a doorway.

Immediately forwards of that is the housing for a large central ventilator with another distinctive louvered top. The port side elevation is more intact. In addition to this massive semi-submerged hulk, there are many artifacts which are preserved from Calypso.

One of the ship’s large stockless anchors is now on display at Embree, while one of the 6” guns that originally was housed in one of the four sponsons is on display back in Portsmouth, UK. Two 3 pdr. Hotchkiss guns said to be from Calypso are also found at the shore establishment in St. John’s, HMCS Cabot, and near Cabot Tower at Signal Hill.13 This last still serves as a Noon Day Gun during the Summer!

Back where it all began, at Chatham dockyards, we are fortunate to have a preserved example of a smaller Barnaby design: A Doterel class sloop. HMS Gannet was about half the size of Calypso, and commissioned five years earlier. Like Scott’s old ship Boadicea, Her hull is composite – wood with iron frames – and she has a more traditional clipper bows.14 However, many of the interior spaces share much in common with Calypso, and this preserved museum ship has a sponson aft and quick-firing Nordenfelts installed!

Do you have old photos of HMS Calypso / HMS Briton that could complement the above post? Please comment!

- The wood planking inhibited galvanic corrosion between the steel and copper, which would accelerate the degradation of the lower hull. When looking at a sectional view of the ship’s hull, the remarkable thing is that the internal structure, bulkheads, deck supports, and hull were all steel, yet the ship had a single layer of planking from the upper deck down to the waterline, then two layers all the way down to a wooden “bolt on” keel -and the usual teak decks- it adds up to an incredible amount of wood used in the construction of a vessel that was structurally metal! ↩︎

- Calypso and sistership Calliope are usually seen with a full three-masted ship rig, but some sources describe the rig as a barque. ↩︎

- These numbers are drawn from the wikipedia article for the class at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Calypso-class_corvette ↩︎

- The Comus class corvettes had a mixture of Rifled-Muzzle-Loaders and early Breech-loaders, with eight broadside guns of the same type of 64-pounder RML to the ones installed on HMS Gannet in the bows. ↩︎

- These technical drawings appear courtesy of the Maritime History Archive, and were compiled in 1881 during Calypso’s construction by Carpenter J.H. Lovett, at Chatham Dockyards:https://collections.mun.ca/digital/collection/calypso/id/355/rec/6. I’d like to acknowledge the assistance of Tanya McDonald, Archivist at the Maritime History Archive, Memorial University Newfoundland. ↩︎

- The term “corvette” would not be revived in naval usage until the early Second World War, with the design of the Flower Class small escort/anti-submarine warships. ↩︎

- https://www.canada.ca/en/news/archive/2015/01/rcn-remembers-first-newfoundland-casualties-great-war.html ↩︎

- Members of the Reserve who died on service are commemorated at Beaumont-Hamel Newfoundland Memorial, and the service is represented at the National Memorial at St. John’s NL with the inclusion of a sculpture of a sailor holding a spyglass. ↩︎

- The facts of Calypso/Briton’s post-1918 disposition were sourced from the interesting article (with photos) “The Last Wooden British Warship; HMS Calypso/Briton” at HiddenNewfoundland.ca: https://www.hiddennewfoundland.ca/hms-calypsobriton ↩︎

- The Newfoundland -Fogo Island-themed website “The Front” at https://thefront2013.wordpress.com/2013/08/17/hms-calypso/

features a post by Amanda Ruth Steven showing photos of Calypso in 2013 (ten years before my visit), and notably uses a press clipping from 1996 which shows a much more intact derelict, including davits, more of the decking, and much more of the ship’s rail still standing above the water. The trawler alongside is named Zarbora, and may be the former Boston Meteor H114 built in Aberdeen (1949). There are more photographs at https://www.hiddennewfoundland.ca/hms-calypsobriton ↩︎ - The youtube video is available on Discovering Newfoundland’s site at, The group maintains a facebook group under the same name. https://youtu.be/j9kjS4HKWAs?si=Y4UOs1MUFRIrQIaV ↩︎

- The deterioration of the steel hull is clearly accelerating, as there are even changes from the video to my visit a year later, 20 August 2023. We saw with my earlier post about the wreck of the SS America/American Star that a derelict steel hull with portions above the water can remain stable for decades, and then collapse in a short period of time. The remaining mizzen mast has collapsed into the water. Visible in the drone footage is a large spar slightly to starboard of the aft quarter on the seabed, which may be the rest of the mizzen mast. ↩︎

- See Calypso guns at Harold Skaarup’s online site: https://www.silverhawkauthor.com/post/artillery-in-canada-10-newfoundland-and-labrador-st-johns-and-hmcs-cabot. The ship’s bell is at the William G. Tilley Museum & Archives, C.L.B., St. John’s. ↩︎

- HMS Gannet and the other Sheerness-built members of the Doterel class of sloops have clipper bows, while the Chatham and Devonport units had straight bows like Calypso’s. ↩︎

“These were the last Royal Navy combatants with a full sailing rig.” Are you sure about that? Interesting article, and very well illustrated.

Thank you! I think I conflated last full rig-sailing corvette with a more general statement. I would defer to your expertise here, and will revise the above. It certainly led me on a merry search to try to establish in all the varieties of 19th C types, what could be regarded as the last with a full rig. Satellite class sloops were concurrent, bigger cruisers seem to have cut down the top hamper after the earlier Nelson class armoured cruisers, the ironclads got out of it earlier…but yes, this period is not my forte as I am more familiar with the earlier Victorian wood and steam navy and the FWW and on…and an almost fanatical interest in the technology of the lost Franklin Expedition and searchers.